David Rothenberg, New Jersey Institute of Technology

Of all the days to schedule a midnight concert live with nightingales in the Treptower Park in Berlin, why did we have to choose May 9th? This could very well be the only night when the park was going to be full of people. This night and this night alone was the 69th anniversary of the end of World War II. Victory Day, a big holiday in Germany although not in the United States. I can see why. We bundle all our war holidays together into Memorial Day and Veterans Day at opposite times of the year to cover all our bases. Too many wars to remember, such bittersweet memories they are. But Germany has many holidays, too many to keep track of. And the end of World War II is of course of far greater significance to Germany than it could ever be to the United States.

And this day is more important in Treptower Park than anywhere else in Berlin, at least, because this is where the great battle of Berlin was fought; where 40,000 soldiers died in just a few days. The park is the site of the grandiose War Memorial, built by the Soviets to commemorate their victory in this grand site in what was once East Germany. Sure, they gave this territory back in 1991, but one of the stipulations in the return was “OK, the Wall is down and you get your country back whole again, but if we give you East Berlin then you must repair our crumbling War Memorial and restore it to its former grandeur.” All right, said the West Germans. You deserve at least that much.

And grand the memorial is, really like no other monument I’ve seen anywhere else in the world. As you enter there is a jagged abstract Russian constructivist style gate with a big hammer and a sickle. At the far end, about 150 meters away, is a 30 meter tall bronze Russian soldier in a long war coat holding up a child, as if to reassure him that he is safe from all the horrors commemorated around him. Beneath the towering statue are sixteen concrete sarcophagi with realist murals carved into the surface, depicting the course of the battle and the courage of the commanders, including more than one image of the once-considered-great Stalin himself.

Yes, the newly united Germans did restore the monument, but in the explanatory text at the entrance that tells this whole story, they seem slightly embarrassed by having to do it. “Although the grandiosity of this monument might seem inappropriate to current memorial style, at the time the language of commemoration was quite different. The War Memorial at Treptower Park should be considered as one of the finest examples of Soviet Socialist Realism, and it has been restored to the best level of authenticity possible.”

In all its strangeness, it is one of my favorite places in Berlin. The weight of history bears down so strongly here, and it is surrounded by quiet forests, a lake, and a beautiful riding path on the shores of the Spree River. It is the most honestly Berlinische of any of the city’s parks, with its mix of roughness, Grand Allées and a strange quality of being out of its time.

Not surprisingly, it is also the best site in the city to find nightingales, and this is why our story takes place here.

Berlin is the best city in Europe to hear the song of the nightingale, and the best time to hear it is late April through late May. This is when the birds return from their migration to Africa, and this is when they establish their territories, sing for their mates, and then nest and prepare to raise their young. By early June the song thins out, and the birds remain in the trees until August, but are much quieter. At the end of the summer, they head south once again.

Why is Berlin the best city for nightingales? And why go to a city for nightingales, when presumably in the countryside the power of bird song resounds more freely, without the incessant noise of human intervention? Well, more people live in cities. And, in cities, people roam the streets at night. Of all songbirds, nightingales are the one species (two species actually) most inclined to sing in darkness as opposed to early morning light. So they are, in addition to their own life stories, characters in human romances and yearnings that happen throughout the night. These are birds celebrated in myth, song, poem and story, and I, for one, read much about them before I ever heard one. When I finally did hear them I couldn’t believe what I heard.

This song was weird. It was not melifluous or melodic like the heavily praised tunes of the hermit thrush in America or the blackbird in Europe. This was some weird kind of rhythmic assault: a series of detached phrases; a mix of rhythmic chirps, spread-out whistles, and funky contrasting noises. I have no doubt that it is music, but an alien music, another species’ groove, a challenge for humans to find a way into. I wanted to know this music, to believe I had a place to join in with it.

You see, I make music with the sounds of other species. I seek them out, all over the world, play my clarinets and other horns along with them; I live, if possible, in their habitat, to imagine I can make music together with sounds I might never understand. The very strangeness of the nightingale’s music is its appeal for me. I am ready to change my own sounds so that together we might produce a sound that no sound could make on its own.

I am telling this story here in the new journal, Performance Philosophy, and you might wonder why indeed the story belongs here at all. Firstly, I am a philosopher who plays music with humans and other animals. You may see my books Why Birds Sing (2005), Thousand Mile Song (2008), and Bug Music (2013) for more of the story. But one could say it is in these musical interactions that I am actually doing philosophy these days, after years of teaching and writing somewhat more conventional books on the subject. Music too is a form of knowledge, and although Wittgenstein famously said “if a lion could talk, we would not understand him,” if a bird sings, somehow we do understand him. And it is in playing or singing back that we might most enhance this understanding.

The fact that it is possible to make music live with nightingales in a big city – in fact, the second largest city in Europe: a burg of nearly three million people – gave me a special kind of hope. A hope that there still some wildness in the city, even though nightingales no longer sing in Berkeley Square, as a famous British song once intoned. The conventional answer as to why there are so many nightingales in Berlin is that the city is relatively quiet, somewhat empty, not all that crowded with humans and containing several very large parks. But maybe there is something else to the story. After all, it’s not only in the parks that one comes across nightingales. Some of them prefer trees in quiet urban neighborhoods, behind a playground or in an abandoned lot, where their tones resound sometimes enhanced by the echoes of an amphitheater of buildings surrounding them. And there’s one famous bird who alights every night atop a traffic light at the main junction in Treptow, right next to the S-Bahn station and the entrance to the park, as if he has specifically chosen the noisiest possible spot to prove his sound can be greater and more tireless than any noise around him.

Everyone is welcome in Berlin, it is truly an international town where those aching to make culture can arrive and soon after find a place. You can join in a scene or create your own scene—there is always a new not-yet-hip neighborhood ready to be colonized by the next group who dares to take over a burned-out building or fix up a crumbling factory. Though prices are steadily rising it is still the cheapest capital in which to set up shop in Europe, and the capital of the Eurozone country with the strongest economy. Not that you will make much money in culture in this capital culture. Here people just do stuff, and don’t demand to be paid for it. And you don’t have to work two frenzied jobs to pay for the privilege of creating culture, as you would have to do in New York. Berlin is easy enough to let you make things happen, and money hardly ever comes up.

So with all this in mind I am not surprised the nightingales like it. They too are outliers, with one of the strangest and most complex songs of any bird on the planet. It does have a definite style and aesthetic, one we humans can’t really pinpoint. As a musician I’m not sure I want to decode it, I just want to join in with it. But Berlin is home not only to the most nightingales in Europe but also the most nightingale scientists. They work out of a lab at the Free University in Dahlem founded by Dietmar Todt, who is now retired. Today the lab is run by Constance Scharff and the nightingale project is directed by Silke Kipper. Students who have passed through this lab over the last forty years now teach and research all over the world (see Hultsch et al 2007). The reason so many scientists are interested in nightingale song is that the nightingales learn their song, they are not born with the songs intact in their brains. In the animal world very few animals can learn with sound: whales, dolphins, songbirds and humans. Not chimpanzees or other primates. Not wolves, dogs, or cats, and most importantly for science not rats, who are the most studied other animals in biology and neuroscience.

Science wants to know how animals learn with sound, or how what they call ‘vocal learning’ develops. This is most easily studied in birds, and biologists like to pick a single ‘model species’ and learn as much as possible about it. They have chosen the Australian zebra finch for this purpose, and literally thousands of scientists study the brain and song-learning abilities of the zebra finch all over the world [reference]. But zebra finches have a very simple song. Simple yes, but how it is produced and appraised is complicated enough to keep legions of scientists busy for years.

So why nightingales? Simply because their song is as different from the zebra finch as you could imagine. It is loud, long, complicated, structured, and musical, an extreme example of what evolution can produce. Evolution has produced it, through sexual selection, generations of female birds preferring ever more musical and complex songs. But how complex really? As complex as possible, or a balance between complexity and simplicity, noise and tone, whistle and crack, similarity and difference, an aesthetic as elusive but graspable as any human style of music? Don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing. If you can’t feel it, you never will. Is music dead? Depends how much you know. And when it comes to nightingales, either we don’t know much or we know a lot, depends on what sort of question you be asking.

But I’m wandering around the Treptower Park hearing the nightingales just begin to sing; it’s after 11pm and the humans are slowly filing out now that the Memorial Concert is over, and I stop for a beer at a small kiosk and a guy bumps into me after he hears me speaking English. “Hey, you are American? What you doing here? On this night of all possible nights!?” He glares at me from a few inches away, vodka on his breath.

His friend pulls him back. “You must excuse Yuri,” says another in a heavy Russian accent. “He has had a bit too much to drink.”

Yuri spits and rumbles away, staring me down as he turns. “My name is Oleg. May I ask you a question?”

I take a slow sip of my beer. “Sure. Why not?”

“Why do you Americans say you won the war? You lost 25,000 men. Russia lost 25 million. It was not your war to win.”

“We don’t think of World War II as our war. It was a world war. The biggest war the world has yet seen. Everyone was dragged into it. Only after the Japanese attacked us did we really feel the sting. And of course we were dead set against Fascism.”

My history was hazy… what about communism? Weren’t we on the same side in that war? Of course so many more Russians died. This was their continent. We stormed in only at the end when the threat couldn’t be ignored. The world was torn asunder. The war to end all wars. That didn’t happen. But no war has yet been quite like it. Hopefully nothing like it could ever happen again. I expected to run into some Russians this night, and have exactly this sort of conversation.

I thought of nightingales in the war; how, every year, the BBC had recorded Beatrice Harrison playing Elgar on her cello to the nightingales in her garden in Kent (see Harrison 2005). It was the first outdoor radio broadcast ever when it was first tried in the twenties and they repeated the ‘stunt’ every year afterwards. Except when the war came. Just then, as they started to record the birds, the roar of German bombers were heard, and they cut the sound off the air. Only years later was the haunting recording of Nazi bombers humming along with singing nightingales released, a solemn warning to us of…. of something. Something deep and profound I think, though I’m not sure what it is.

Yes I am. It’s that something about the eternal presence of these beautiful alien songs in our midst, always just beyond our power to comprehend. The science of nightingale songs is profound and amazing but we still may never comprehend their all-surrounding beauty, a beauty far older than the human species and a song that will hopefully outlast us ever still. I’m sure they were trying to sing that fateful May 9th, 1945 as so many Russian lives were lost in the defense of noble Berlin.

After almost an hour discussing the weight of history with Oleg and Yuri we come to some kind of agreement, if only because I agreed to listen. “Well,” Oleg put his arm around my shoulder as he tried to steady himself, “at least there is one good American here I can trust” and he and his friends wobbled off into the night.

In fact, everyone seemed to be deserting the park. I couldn’t believe it. 1130pm and the festivities were over. That’s just about when Berlin is supposed to wake up! At least the nightingales were waking up. At midnight we would meet the audience, who had paid good money for this concert, and we would all head into the night.

So many things had been conspiring to ruin this evening! The recurring threat of rain, my friends kept calling for some reassurance that I had called the whole thing off—I kept saying the same thing: it’s not gonna rain. Then the great celebration of Victory Day—even that was now quieting down. The skinheads by the station were getting a bit edgier, but still they seemed inclined to leave us alone. In the distance the songs welled up in the trees. Concert time was soon upon us.

A small group of dedicated interspecies musical adventurers had gathered. They were not afraid of rain, or of revelling Russians. Neither were the nightingales afraid of either. Why Rosa Luxemburg herself had once noted this, sitting by her prison window:

At six o’clock, as usual, I was locked up. I sat gloomily by the window with a dull sense of oppression in the head, for the weather was sultry. Looking upward I could see at a dizzy height the swallows flying gaily to and fro against a background formed of white, fleecy clouds in a pastel-blue sky; their pointed wings seemed to cut the air like scissors.

Soon the heavens were overcast, everything became blurred; there was a thunder storm with torrents of rain, and two loud peals of thunder which shook the whole place. I shall never forget what followed. The storm had passed on; the sky had turned a thick monotonous grey; a pale, dull, spectral twilight suddenly diffused itself over the landscape, so that it seemed as if the whole prospect were under a thick grey veil. A gentle rain was falling steadily upon the leaves; sheet lightning flamed at brief intervals, tinting the leaden grey with flashes of purple, while the distant thunder could still be heard rumbling like the declining waves of a heavy sea. Then, quite abruptly, the nightingale began to sing in the sycamore in front of my window.

Despite the rain, the lightning and the thunder, the notes rang out as clear as a bell. The bird sang as if intoxicated, as if possessed, as if wishing to drown the thunder, to illuminate the twilight. Never have I heard anything so lovely. On the background of the alternately leaden and lurid sky, the song seemed to show like shafts of silver. It was so mysterious, so incredibly beautiful, that involuntarily I murmured the last verse of Goethe’s poem, “Oh, wert thou here!” (Luxemburg 1917)

How to describe the loveliness of such a sound? To me it is more than anything else an alien music. Music quite clearly, but not as we know it. A more-than-human aesthetic is clearly at work. I use that lovely “more-than” phrase coined by my friend David Abram, since “non-human” seems so pejorative, and even alien sounds unnecessarily distancing. Let’s place these birds as part of something larger than us, since they and their aesthetic evolution has been with us for so much longer than the time when the human species was born.

Why so much song from one little brown bird? It is indeed excessive, and risky. One male nightingale singing on one perch for hours on end through the night could easily be picked off by a tawny owl, no problem. They take the risk. But nevertheless, the song is intricate, involved, and some would say excessive. According to the aesthetic selection theory I wrote about in Survival of the Beautiful (2012), this bird has evolved such a nuanced aesthetic only through the connoisseurship of female nightingale. They and only they know just what kind of song is the best song. We can listen, study, surmise, calculate, measure, and dare to join in but the whole inhabitation of the nightingale aesthetic still manages to elude us. Perhaps it always will, and we should be glad of that.

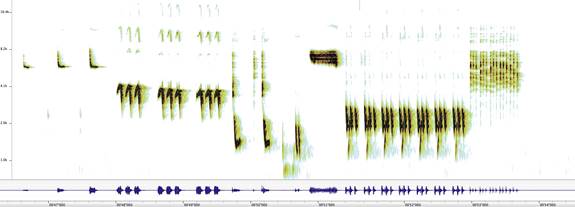

But that doesn’t stop us from trying. So many ways to try! Silke Kipper leads the research group on nightingale song at the Free University in Berlin and they have tried Markov chain analysis, network theory, and all kinds of statistical analysis to compare one bird with another. As scientists, the researchers tend to consider each single, detached nightingale phrase as one song; whereas I, as a musician, tend to consider the whole hour-long performance as a song, with each individual statement as one phrase that’s part of the whole. She has found some birds to sing in an ‘orderly’ fashion, where certain sequences of songs (or phrases) seem to regularly recur, and other birds sing in a random or disorderly chaotic fashion where no sense of order can be decreed. The majority of these songs are composed of whistles, clicks, and rattles, not the usual components of music as humans know it.

But humans have for centuries praised and loved the songs of nightingales, and re-framed them in many kinds of poetry, as Borges himself once noted:

…Your voice, burdened with mythology,

Nightingale of Virgil, of the Persians?

Perhaps I never heard you, yet my life

I bound to your life, inseparably.

A wandering spirit is your symbol

In a book of enigmas. El Marino

Named you the siren of the woods

And you sing through Juliet’s night

And in the intricate Latin pages

And from the pine-trees of that other,

Nightingale of Germany and Judea,

Heine, mocking, burning, mourning.

Keats heard you for all, everywhere.

There’s not one of the bright names

The people of the earth have given you

That does not yearn to match your music… (Borges 1977)

So many references to nightingales by so many who have never heard the original creature! The key thing about the bird is that he does not sound as melodious as he is often described. John Elder, literary scholar was as surprised as I on his first trip to Europe to hear said bird, and he said our human love of the nightingale’s song has as much to do with the range, energy, and ability of the song to carry far through the trees as it does to do with anything specifically musical in the song. There is such energy and passion in the sound that makes it seem as if this bird might die from his music if he had to. Does that ever happen? I don’t think so.

Scientists like Kipper try to decipher the birds’ scratching and sampling with as little reference to human musical categories as possible. That is because she and most scientists call our musical ideas humanly subjective, and thus less relevant to science than the penchant to count, measure, and enumerate. She feels her numbered approach is as close to pure phenomenology, the sound in itself, as we can get.

Those like myself who consider music, science, and poetry to be three different, separate and equal human ways of knowing tend to agree with most philosophers in suggesting that all these things are particularly human ways of knowing, and that none of them on their own will enable us to learn what it is like to be a nightingale, something that Thomas Nagel once thought was impossible but given his recent turn toward the nonmaterialist, he may have changed his tune (see Brody 2013). I shall have to take him out in the field to listen to bird song sometime.

Scientists are by their creed far more impressed with order than disorder, and thus Kipper is worried by the occasional penchant of the male nightingale to sing a strange “buzz sound” in the midst of his clarion whistles, clicks, and ratchets. She admits she finds this buzz sound (she calls it a buzz song) unpleasant, and says that does not matter because the female nightingales find it especially pleasant.

Meanwhile I had noticed this sound already has something particularly cool that the nightingales would sing only occasionally, like an ornament, grace note, or more honestly a blue note, that cool in-between unclassifiable sound human music is known to offer up in many forms. If not a buzz sound then a fuzz tone, a hip tone, a most excellent riff that only makes sense if it is not used too often.

Now would the nightingales use it all the time if they could. Kipper suggests that this sound must be hard for the birds to make, so it suggests real control of the ‘syrinx’ (like the larynx, but in birds it lets them sometimes make two tones at once). When a female hears this, she knows that this male singer is strong, solid, and a good choice with whom to mate. It gets her excited. She just might fly right into the midst of the nettles to find him…

But why, why does this cool bluesy buzz have to mean something? What does it mean when humans do it? Sure, I’ve heard all sorts of explanations for the lure of the blue note, the uncanny, the in-between the wrong that is right. One common one for the blue note is that it is the note that comes in the harmonic series, closer to the nature of sound and farther from the nature of our tempered scale. That sounds reasonable, but I don’t know if it’s true. There are so many ways to ground sound in the ineffable—the breathy pillow underneath a jazz clarinet sound, the gliss, the bend, the slide from Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. You simply cannot to this stuff all the time. Music is an exercise in contrast between the expected and the surprise, between the beat and the stop, the pattern and the un-pattern.

So what is it like to play along with a nightingale? It becomes a direct window into the unknown, a touch of communication with a being with whom we cannot speak. The play of pure tones jarring against click and buzz, it all becomes not a code but a groove, an amphitheater of rhythms in which we strive to find a place. I am listening right now to a recording made by the lake in Treptower when there are a series of nightingales each vying for their territories, and an occasional dove in the background. What is special about this moment is that the birds are leaving space for each other, they are in that back and forth, territory-defining state, and thus they welcome me perhaps more than usual. Occasional human cries in the distance, that’s right, everyone can find their place, all are welcome…. Finally one screech—is it someone blowing against a blade of grass?—will that silence our bird? No, absolutely not, nothing will. For he is born to sing.

I still feel I am not quite getting it, perhaps there is little that needs to be said. But I want to convey to you that there is something special about jamming with another species. I don’t know if jamming is the word. Does that suggest something frivolous to you? Musicking? Playing along with? Finding common ground? Interspecies music, of course, is music that no one species could make all on its own. And the whole – if it works – should be greater than the sum of its parts. Like nature is greater than any one species in its midst. We all have our place, and no species is an island. We enhance ourselves by paying more attention to the rest of life!

What does it take for a human to like this buzz? Allude to the irregular, the off, the hard to place, the thing science doesn’t want to admit. Science can admit it of course, that we too like the uncanny, the blue. The ‘just enough’ of the sound we won’t expect.

One song or many, what is that bird up to? Many songs all in a row, up to a few hundred in a song ‘bout,’ or one multiplicitous song out of many riffs or phrases. How much space between each sound? How much listening goes on in those silences? I want to listen as much as the bird does. I imagine a music we make together is much more than a war. We don’t fight each other for attention, but strive together for comprehension.

Still people ask me what it feels like, and I feel like I never give a good enough answer. That’s why I have to do it, just play music tuned to the moment and the presence of the birds and leaving space for the silences. I will have to say that it was uniquely moving to bring a patient audience of about twenty-five people out into the Treptower Park an hour after the Russian Victory festivities had subsided and a strange calm descended on the night. Only then did the birds rise up in ascendance, as if they enjoyed all that noise and human celebration of the end of the Second Great War. Kipper confirms this; nightingales actually seem to enjoy singing after and amidst the everpresent noise of humans. They are not afraid of us; they coexist with us, hiding in their nettle fortresses, waiting for the right moment, singing away. Although at first she was a bit worried, we do not mess them up by messing with their heads and playing music in their midst. We honor their song by calling it a song, by deciding it is something worth taking seriously as music and finding a way in which to join in.

I say this again and again, and it does seem after a while a refrain, the same simple message, one easy way to make nature matter. Listen to it, and don’t sit passive but love it enough to want to play along. It’s got room for you.

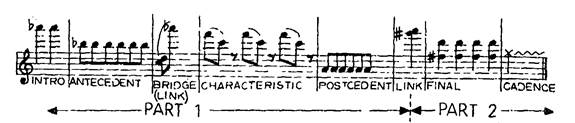

So how to best describe this song of a nightingale? Musical transcription doesn’t do it; sonograms can do it but still seem like a secret kind of code. Johann Matthaus Bechstein, a forester and pioneer conservationist in Germany, transcribed the nightingale song as follows in the late eighteenth century:

Tioû, tioû, tioû, tioû.

Spe, tiou, squa.

Tiô, tiô, tiô, tiô, tio, tio, tio, tix.

Coutio, coutio, coutio, coutio.

Squô, squô, squô, squô.

Tzu, tzu, tzu, tzu, tzu, tzu, tzu, tzu, tzu, tzi.

Corror, tiou, squa, pipiqui.

Zozozozozozozozozozozozo, zirrhading!

Tsissisi, tsissisisisisisisis.

Dzorre, dzorre, dzorre, dzorre, hi.

Tzatu, tzatu, tzatu, tzatu, tzatu, tzatu, tzatu, dzi.

Dlo, dlo, dlo, dlo, dlo, dlo, dlo, dlo, dlo.

Quio, tr rrrrrrrr itz.

Lu, lu, lu, lu, ly, ly, ly, ly, liê, liê, liê, liê

Quio, didl li lulylie…. (Bechstein 1795)

Rrrrrrr! Is that famous buzz song. This is thirty years before John Clare and a hundred and twenty years before Kurt Schwitters and Dada. It seems as though no one was especially impressed by this formidable language at the time. It took more than a century before we humans were able to hear this as music, or as poetry.

Like any foreign music, the nightingale’s music is all the more accessible the more time you spend within it. As a listener, just listen further. Don’t tune out once you have identified the species behind the song. Remember that hearing can be forgetting the name of the thing one hears, but remembering how much more the song means to the bird than it will ever mean to you. As a musician, as a player, dare to join in. The nightingale pauses in his renditions after each phrase to give you a moment to think about it; to challenge, acknowledge, or ignore, depending on how you feel about it. It is a microcosm of all music, a study in similarity and difference, in repetition and novelty, in noise and rhythm versus melody and pure tone. It is always more and less than anything we can add or take away from it. Possibly that is because the song has been around for millions of years, longer than humans have been on the planet, and it will remain long after we are gone.

Its rhythms are not boring, its melodies continue to surprise. Why is that? Perhaps it’s because we can never quite get it, this song never designed for us to listen to at all.

Or is it? Maybe we have an obligation, or a duty, to take it far more seriously than we have ever done. Maybe we are finally ready to do it.

Recordings of Rothenberg and Korhan Erel performing with nightingales in Treptower Park:

Album available at: http://www.pledgemusic.com/projects/berlinbulbul.

Bechstein, Johann Matthias. 1795. The Natural History of Cage Birds: Their Management, Habits, Food, Diseases, Treatment, Breeding, and the Methods of Catching Them. London: Groombridge and Sons. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/40055.

Borges, Jose Luis. 1977. ‘To The Nightingale.’ The New Yorker. May 9. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1977/05/09/to-the-nightingale.

Brody, Richard. 2013. ‘Thomas Nagel: Thoughts Are Real.’ The New Yorker. July 16. http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/thomas-nagel-thoughts-are-real .

Harrison, Beatrice. 2005. ‘The Cello and Nightingale Sessions.’ Music and Nature. http://musicandnature.publicradio.org/features/.

Hultsch, Henrike, Sarah Kiefer, Philipp Sprau, Constance Scharff, and Christina Sommer. 2007. ‘Behavioural Ecology and Song Characteristics: A Long-Term Field Study on a Berlin Population of Individually Banded Nightingales.’ Institute of Biology – Department of Biology, Chemistry, Pharmacy – Freie Universität Berlin. June 17. http://www.bcp.fu-berlin.de/en/biologie/arbeitsgruppen/neurobiologie_verhalten/verhaltensbiologie/forschung/nachtigallenforschung/nachtigallen-projekte/pr-all-behavioral-ecology.html .

Luxemburg, Rosa. 1917. ‘Letters to Sophie Liebknecht (Wronke, End of May 1917).’ Translated by Eden Paul and Cedar Paul. http://www.marxists.org/archive/luxemburg/1917/undated/01.htm .

Rothenberg, David. 2005. Why Birds Sing: A Journey into the Mystery of Birdsong. New York: Basic Books.

———. 2008. Thousand Mile Song. New York: Basic Books.

———. 2012. Survival of the Beautiful: Art, Science, and Evolution. London: Bloomsbury.

———. 2013. Bug Music. New York: St Martin’s Press.

David Rothenberg has written and performed on the relationship between humanity and nature for many years. He is the author of Why Birds Sing (Basic Books, 2005), on making music with birds, also published in England, Italy, Spain, Taiwan, China, Korea, and Germany. It was turned into a feature length BBC TV documentary. His following book, Thousand Mile Song (Basic Books, 2008), is on making music with whales. It was turned into a film for French television. David Rothenberg is Professor of Philosophy and Music at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, which has encouraged and supported all of his creative projects since 1992. As a composer and jazz clarinetist, Rothenberg has eleven CDs out under his own name, including On the Cliffs of the Heart (1995), named one of the top ten CDs by Jazziz Magazine in 1995 and a record on ECM with Marilyn Crispell, One Dark Night I Left My Silent House (2010). Other releases include Why Birds Sing (2005) and Whale Music (2008).

© 2015 David Rothenberg

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.