The Paradox of a Gesture, Enlarged by the Distension of Time:

Merleau-Ponty and Lacan on a Slow-Motion Picture of Henri Matisse

Painting

Astrid Deuber-Mankowsky, Ruhr University Bochum

translated by Markus Hardtmann

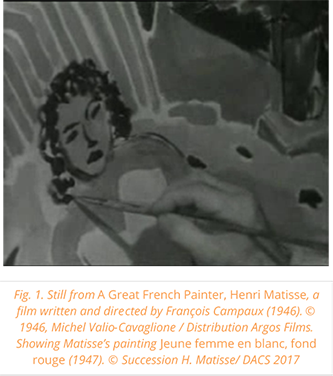

In his 1964 series of lectures, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Jacques Lacan

briefly mentions a “delightful example” (1981, 114) that

Maurice Merleau-Ponty had given in an excursus to his book, Signs (1964c, 45–6). Lacan describes it as

“that strange slow-motion film in which one sees Matisse

painting” (114). What the psychoanalyst is referring to is a

scene in the documentary Henri Matisse by François

Campaux, a 16-mm black-and-white sound film from 1946.

Lacan mentions Merleau-Ponty’s interpretation of the filmic

example only in passing. This reference, however, is anything but

arbitrary, for it marks the conclusion of an intense altercation he had

with the aesthetics of perception and ontology of Merleau-Ponty, who

had passed away three years earlier. Lacan had been friends with the

philosopher since the early 1940s (Roudinesco 1997, 210). Seven days

after Merleau-Ponty passed away, Lacan expressed his grief on May 10,

1961, to a full auditorium with the following words:

It was a heavy blow to us. […] I can also say that because of

this mortal fatefulness, we will not have had time to bring our

formulations and statements closer together. (cited in Roudinesco 1997,

280; translation modified M.H.)[1]

The differences alluded to by Lacan refer to an intervention by

Merleau-Ponty at a congress in Bonneval in the autumn of 1960. At the

meeting, Lacan defended his thesis that the unconscious is structured

like a language against the advocates of a phenomenological

Freudianism. Lacan is said to have counted on Merleau-Ponty’s

support, but the latter rejected Lacan’s thesis as totalitarian

(Roudinesco 1997, 254; also see Lacan 1981, 71).

How strongly Lacan felt about the need for a clarification of their

respective positions can already be seen from the short article that he

wrote as an homage to Merleau-Ponty in 1961, published in a special

issue of the journal Les temps modernes dedicated to

the philosopher. In Merleau-Ponty’s last published article,

“Eye and Mind” (first published 1961; written July 1960),

in particular, and especially in the remarks on painting developed

therein, Lacan saw a point of connection between their respective

positions. Thus Lacan declares his agreement with Merleau-Ponty’s

view that there is a reality at work in painting that affords it a

truth function sui generis. Lacan emphasizes the fact that

painting is the truth function of a reality that cannot be captured

physically and has to remain invisible for the natural sciences.

In the following discussion of how Merleau-Ponty and Lacan refer to the

filmic example showing Matisse painting, I will not seek to reconstruct

Lacan’s altercation with Merleau-Ponty. Rather, I would like to

pursue the following two questions: First, I will reconstruct the

different ways in which Merleau-Ponty and Lacan determine, in their

respective discussions of the recording of Matisse painting, the

mediality of gesture in the constitution of the subject. Merleau-Ponty

raises the question of an ethics of gesture by situating the subject in

the field of tension between rationality and the presence of bodily

experience: gesture establishes the link to the reality of the creative

act and leads to “this fabric of brute meaning” (cette nappe de sens brut) which, according to Merleau-Ponty,

the “activism [of scientific thinking] would prefer to

ignore” (Merleau-Ponty 1964a, 161).[2] At the same time,

gesture functions as a protection against the intellectualiziation (Vergeistigung) that threatens the subject when

rationality takes on a life of its own. Lacan takes up the argument at

the precise point where Merleau-Ponty, in contradistinction to Platonic

philosophy, assumes that we are beings who are looked at, rather than

beings looking at the truth of the world in the ideas. That is to say,

Lacan likewise starts out from the pre-existence of the gaze—and

thus also from gesture. Unlike Merleau-Ponty, however, Lacan does not

assume that gesture leads to a “fabric of brute meaning”;

for him, it leads to the split of the subject. As I am going to explain

in more detail, gesture is characterized, for Lacan, by a paradox that

manifests itself as arrest and haste in the dimension of time, and as

fissure and suture in the dimension of space. The question of an ethics

of gesture also arises for Lacan in relation to the recognition of the

limitedness of the subject. Whereas Merleau-Ponty associates the latter

with the recognition of the intimacy between mind and body, however,

Lacan connects it to the recognition of the split nature of the

subject.

What role do the philosopher and the psychoanalyst ascribe to the

technical in their critique of an intellectualizing philosophy of mind

(Geistesphilosophie)? This is the second question

that is going to guide my reflections on the mediality of gesture.

After all, the “strange[ness]” (Lacan 1981, 114) of the

filmic example is the result of a strategically used technical

intervention: slow motion. Do Merleau-Ponty and Lacan take the specific

productivity of the technical into account? And if so, how do they

reflect on it? Do they develop concepts that would allow one to plumb

the new, previously unseen, aesthetic spaces that have become possible

with technical media of reproduction? Or do Merleau-Ponty and Lacan, in

their critique of the philosophy of reflection and substance,

ultimately reproduce the very dichotomies of this philosophical

tradition? If this were the case, then—and this is will be my

final thesis—their approach towards an ethics of gesture would

have to be reconsidered.

The Artificiality of Slow Motion

The film begins with a female model clad in a bright, wide dress

entering Matisse’s studio—a space suffused with light. The

model sits down in an armchair, and the master adjusts her position and

arranges her dress a bit. Merleau-Ponty does not mention the gender

coding of the scene, while Lacan comments on it only indirectly, along

the lines of his psychoanalytic reading. At first, the scene unfolds at

the usual speed. The camera wanders from the model to the easel, before

focusing on the canvas and the hand of Matisse, who is holding a brush

and transferring the outlines of the face and the hair with a

succession of deliberate brushstrokes onto the canvas. The scene is set

to a movement with much forward momentum from César Franck’s

well-known symphony in D minor, and it is accompanied by a voice-over

that rushes forth in a similar manner. At the conclusion of the scene,

it is repeated, but this time it has been recorded at a much higher

frame rate and thus appears in slow motion when it is replayed at

normal speed. This shift is also marked acoustically by a change in

rhythm. As the voice-over comments, “grace au cinéma,”

thanks to the technology of cinema, one is able to analyze, in slow

motion, the gestures with which Matisse transfers paint onto the

canvas.

The film begins with a female model clad in a bright, wide dress

entering Matisse’s studio—a space suffused with light. The

model sits down in an armchair, and the master adjusts her position and

arranges her dress a bit. Merleau-Ponty does not mention the gender

coding of the scene, while Lacan comments on it only indirectly, along

the lines of his psychoanalytic reading. At first, the scene unfolds at

the usual speed. The camera wanders from the model to the easel, before

focusing on the canvas and the hand of Matisse, who is holding a brush

and transferring the outlines of the face and the hair with a

succession of deliberate brushstrokes onto the canvas. The scene is set

to a movement with much forward momentum from César Franck’s

well-known symphony in D minor, and it is accompanied by a voice-over

that rushes forth in a similar manner. At the conclusion of the scene,

it is repeated, but this time it has been recorded at a much higher

frame rate and thus appears in slow motion when it is replayed at

normal speed. This shift is also marked acoustically by a change in

rhythm. As the voice-over comments, “grace au cinéma,”

thanks to the technology of cinema, one is able to analyze, in slow

motion, the gestures with which Matisse transfers paint onto the

canvas.

Lacan’s mention of the scene refers to the description and

interpretation of it by Merleau-Ponty, which I would now like to

present. Merleau-Ponty introduces the scene with the following words:

A camera once recorded the work of Matisse in slow motion. The

impression was prodigious, so much so that Matisse himself was moved,

they say. That same brush which, seen with the naked eye, leaped from

one act to another, was seen to meditate in a solemn and expanding [dilaté] time—in the imminence of a world’s

creation—to try ten possible movements, dance in front of the

canvas, brush it lightly several times, and crash down finally like a

lightning stroke upon the one line necessary. (1964c, 45)

As Matisse himself reported, he felt “naked” when he saw

the scene showing his gestures. The “strange journey” made

by his hand was not, as he emphasized, a sign of hesitation. Rather, he

was “unconsciously establishing the relationship between the

subject” he was about to draw and the size of the paper (cited in

Bois 1990, 46).[3]

While Lacan will highlight the ambivalence expressed in Matisse’s

look at himself and the movements of his brush and connect this

ambivalence to the sovereignty of the unconscious, Merleau-Ponty bases

his interpretation on the analysis put forward by the voice-over. In

the commentary, the voice-over emphasizes that Matisse’s gestures

appear carefully considered when viewed in slow motion, as though the

artistic act arose from a process of meditating and measuring and were

based on an act of reflection, of calculation, and of conscious choice.

The important point is that calculation and choice do not need to

exclude one another on the level of reflection. Against this backdrop,

Merleau-Ponty interprets the gestures circling above the canvas as a

scanning of possible lines in order to realize, out of an infinite

number of possibilities, the one, optimal line. As Matisse is shown

painting in slow motion, he is reminiscent of the God of Leibniz who

acts rationally in a particular way: following the rule that the

greatest variety of things must be combined with the greatest order, he

chooses, out of an infinite number of possibilities, the best one. The

choice made by Leibniz’ God is not predetermined, but it is

nonetheless necessary, and can, at least in principle, be predicted.

Merleau-Ponty does in fact compare Matisse filmed in slow motion to the

God of Leibniz, who chooses the perfect world among all possible worlds

and thereby solves the difficult problem of minimum and maximum.

However, Merleau-Ponty adds that Matisse would be wrong if, putting his

faith in the film, he assumed that he did indeed proceed like God. This

impression is “artificial” and, as Merleau-Ponty makes

clear, owes itself entirely to the technology (Technik) of

slow motion (1964c, 45).

It is not difficult to recognize in this critique—and in the

comparison with Leibniz’ God who chooses among infinite

options—the critique of the “cybernetic ideology”

that Merleau-Ponty formulated in his essay “Eye and Mind.”

As Merleau-Ponty maintains, cybernetics transforms operational thought

into an “absolute artificialism” ( artificialisme absolu) and derives “human creations

[…] from a natural information process, itself conceived on the

model of human machines” (1964a, 160). Cybernetics thus

represents, for Merleau-Ponty, an apex of the rationalist tradition. It

belongs to a philosophy of pure vision that substitutes an intellectual

eye for the perceiving eye, and replaces the world with a model of the

world or, as Merleau-Ponty laconically puts it, with its “[b]eing

thought” (1964a, 176).

Opposing this cybernetic way of thinking, Merleau-Ponty demands that:

Scientific thinking—that is, a thinking in overflight (pensée de survol), a thinking of the

object-in-general—must return to the ‘there is’ which

underlies it; to the site, the soil of the sensible and opened world

such as it is in our life and for our body—not that possible body

which we may legitimately think of as an information machine but that

actual body I call mine, this sentinel standing quietly at the command

of my words and my acts. (1964a 160–1; translation modified,

M.H.)

The body here functions as a sentinel not only against the

“overflight” of scientific thinking, but also as a guard

protecting the connection between body and life against a technology

associated with “artificiality” and the ideology of

cybernetics.

When Merleau-Ponty describes the slow-motion film as

“artificial,” he is not implying that it is fictional. He

is suggesting, rather, that it makes us believe that “the

painter’s hand operated in the physical world (monde physique) where an infinity of options is

possible,” instead of showing us the event “in the human

world of perception and gesture” (1964c, 46). According to

Merleau-Ponty’s interpretation, slow motion shows Matisse

painting from the perspective of rationalist and scientific thinking.

In this way, however, the film misses what it purports to analyze: the

reality of the creative act. For Merleau-Ponty, the reality of the

creative act can only be grasped from the situated, partial perspective

of perception, which is conditioned by corporeality. This situated

perspective, in turn, is based on the supposition that human beings do

not primarily stand opposed to the world; they are, rather, a part of

life which, according to Merleau-Ponty, grounds the meaning and the

becoming visible of things. How closely related aesthetics and aisthesis are in Merleau-Ponty is shown by his

interpretation of art works—and especially images—as

“signs for the points of view of seeing” (Wiesing 2000,

274). His philosophy is a kind of Leibnizian Monadology, as it

were—a Monadology, however, that does not find its final reason

in the vision of God, but posits the belief in perception as the start

and endpoint of the questions it pursues. Accordingly, Merleau-Ponty

regards the difference between these viewpoints—a difference that

is expressed in the style of an image—as the condition for the

possibility of generating meaning in painting and language. This, then,

is the sense in which one should understand Merleau-Ponty’s

proposition: “But art, especially painting, draws upon this

fabric of brute meaning [sens brut] which [the] activism [of

scientific thinking] would prefer to ignore” (1964a, 161).

Despite appearances to the contrary, the painter emerges as a sovereign

subject from Merleau-Ponty’s interpretation of the filmic

example. His sovereignty, however, is not based on a comparison with a

God but relates, instead, to that which connects the painter, through

his body, with the “flesh […] of the world” (1964a,

186): namely, his individual situatedness in space and time. The

painter is, according to Merleau-Ponty, “incontestably sovereign

in his rumination (rumination) of the world. With no

other ‘technique’ than what his eyes and hands discover in

seeing and painting” (161).

As this citation indicates, Merleau-Ponty places the technical on the

side of reflection and scientific thinking in his interpretation of the

filmic example. He describes both as “artificial,” as a

thinking in “overflight” (survol). Hence, we can

infer that for Merleau-Ponty, “the technical” belongs to

the rationalist tradition that he seeks to ground ontologically in the

context of his new philosophy. Merleau-Ponty believes that this

grounding can be accomplished by means of a

“hyper-reflection” (surréflexion) that traces

reflection and scientific thinking back to an original bond with the

world, which is experienced in the corporeality of perception.

This identification of thinking and rationality corresponds precisely

to a remark made by Merleau-Ponty in his well-known lecture “The

Film and the New Psychology” (1964d, 48–62). Addressing the

relation between cinema—which is after all a technical

invention—and Gestalt psychology, Merleau-Ponty affirms that

“after the technical instrument has been invented, it must be

taken up by an artistic will and, as it were, re-invented before one

can succeed in making real films” (1964d, 59). But what are

“real films”? For Merleau-Ponty, they are films that make

us sense, by means of technology—for instance, through the use of

montage—“the coexistence, the simultaneity of lives in the

same world” (55). They are films that “make manifest the

union of mind and body, mind and world, and the expression of one in

the other” (59). In light of this, the slow-motion film of

Matisse painting would have to be described not only as artificial, but

also as unreal. For in this scene, technology intervenes in the

customary perception of the world and does not adapt to the intimacy of

body and mind described by the philosopher.

Small Strokes Raining from the Brush

Lacan’s reference to the “delightful example” occurs

at the end of the second part of his lecture series On the Gaze as Petit Objet a, which would become very

important in the history of psychoanalytic film theory. In his first

lecture on February 28, 1964, Lacan already announces that his

discussion of the scopic function would be inspired by

Merleau-Ponty’s unfinished book The Visible and the Invisible, which had recently been published

posthumously (Lacan 1981, 71). With the insight that the idea and

philosophical tradition of Idealism had proverbially been guided by the

eye, Merleau-Ponty brought to light, according to Lacan, the point at

which the philosophical tradition that had begun with Plato’s

theory of ideas reached its end in the middle of the 20th century (71).

Indeed, Merleau-Ponty describes the primacy of perception in his late

work in terms of an interrogation already at work in perception

itself—that is, in the gaze—rather than only in

philosophical reflection (Waldenfels in Burke and Van der Veken 1993,

3). As he maintains, it is “not only philosophy, it is first the

gaze that questions things” (Merleau-Ponty 1968, 103).

In this context, Merleau-Ponty’s claim that we are not, as Plato

would have it, beings who look at the truth of the world in the ideas

but, rather, “beings who are looked at, in the spectacle of the

world,” acquires a particular significance (Lacan 1981, 75). For

Lacan, this insight marks the proximity between his own interpretation

of the scopic function and Merleau-Ponty’s analysis of the eye

and the gaze. By showing that we are beings who are looked at,

Merleau-Ponty opened up “that new dimension of meditation on the

subject that,” as Lacan literally puts it, “psychoanalysis

enables us to trace” (1981, 82; translation modified, M.H.).

Together with Merleau-Ponty, Lacan assumes the pre-existence of the

gaze, but he does not relate it to a scopic point of origin. In his

analysis of the phrase “I see only from one point, but in my

existence I am looked at from all sides,” Lacan instead describes

the gaze as a “bipolar reflexive relation” (1981, 81). He

does not equate the split above which the subject constructs itself

with the distance between the visible and the invisible. Summarizing

the decisive difference to Merleau-Ponty, Lacan maintains, rather, that

the “gaze is presented to us only in the form of a strange

contingency” (1981, 72).

To return to the example of the film, Lacan’s insistence on the

role of contingency in the constitution of the gaze leads him to

describe Matisse’s brush strokes not as the sovereign gestures of

a creative artist, but as “the rain of the brush,” as

“little strokes raining from the painter’s brush” in

a particular “rhythm” (1981, 114; translation modified,

M.H.).[4] In a series of

strong images that allow the reader to sense the “strange

contingency” of the gaze, Lacan then compares the “rain of

the brush” with the feathers a bird lets fall, the scales a snake

casts off, and the leaves a tree allows to tumble down.

Lacan agrees with Merleau-Ponty’s view that it is an

“illusion” that every brush stroke by the painter is

perfectly deliberate. But the conclusions Lacan draws from this fact

are different. According to Lacan, it is not slow motion that is

deceptive. Rather, slow motion shows “the paradox of this

gesture”—of a gesture, that in its turn seeks to

deceptively suggest the “subject is not fully there,” but

that she is, as Lacan puts it, “remote-controlled ( téléguidé)” (Lacan 1981, 115; translation

modified, M.H.). With this reference to remote control, Lacan’s

formulation indicates that the technical will come into play here. Yet

in this particular context, the technical has nothing to do with film

per se; it relates instead to the scientific status that Lacan accords

to the psychoanalytic meditation on the subject.

While Merleau-Ponty denies the scientificity of phenomenology, Lacan

follows Freud in holding on to the idea that psychoanalysis is a

science. However, the Freudian question of what kind of science

psychoanalysis might be is given a new and decisive twist by Lacan: he

relates it to the question concerning the origin of modern science as

such. As Lacan specifies, the “science in which we are caught up,

which forms the context of the action of all of us in the time in which

we are living, and which the psycho-analyst himself cannot escape,

because it forms part of his conditions, too, is Science itself” (1981, 231). In Lacan’s reading, it

becomes apparent that the concept of science in the modern sense is not

older than the concept of the subject, whose truth is the concern of

psychoanalysis. Both concepts lead Lacan back, not to Leibniz and the

Monadology, but to Descartes, his methodological doubt, and his voluntaristic conception of God. In Lacan’s discussion

of the history of philosophy, Descartes appears as a precursor to the

discovery of the unconscious.

The founder of Rationalism seeks certainty for the subject, as Lacan

explains, and at first finds it in the sentence: I doubt, therefore I think. But how could this statement lead to the phrase: I

doubt, therefore I am? Or to use a formulation of

Lacan’s, how could it lead to the sentence: “by virtue of thinking, I am” (De penser, je suis) (1981, 35; 1990, 44)? In order to

accomplish this transition, Descartes takes up the ontological proof of

God; that is, he infers, from the thinking of man, the thought of God,

in whom Being and Thinking coincide. According to Lacan, Descartes thus

situates the field of knowledge “at the level of this vastest of

subjects, the subject who is supposed to know [le sujet supposé savoir], God” (224; translation

modified, M.H.; 1990, 250). And thus Descartes performed, as Lacan

comments, “one of the most extraordinary sleights of hand [tours d’escrime] that has ever been carried off in the

history of mind [l’histoire de l’esprit].”

By giving “primacy […] to the will of God” (225), the

founder of modern science put God in charge of eternal truths. In other

words, “what Descartes means, and says, is that if two and two

make four it is, quite simply, because God wishes it so” (225;

1990, 251).

“I dare to state as a truth,” Lacan writes, “that the

Freudian field was possible only a certain time after the emergence of

the Cartesian subject, in so far as modern science began only after

Descartes made his inaugural step” (1981, 47). This link between

psychoanalysis, science, and the cogito, however, only became

apparent in retrospect; that is, after Freud had revised the certainty

of the subject. Unlike Descartes, Freud does not assume the existence

of an infinite, omniscient substance that would guarantee the eternal

truths; on the contrary, Freud demystifies such an assumption as

wish-fulfillment. What is certain for Freud, according to Lacan, is

that here, “in this field of the beyond of consciousness,”

there are thoughts, which Lacan in turn interprets as chains of

signifiers (44). If Descartes situated the subject at the level of the

vastest subject, God, who is supposed to know, Freud locates it in the

field of the unconscious. This means that Freud put everyone, including

Lacan, in a position to think the subject in relation to the reality of

desire.

With this step, Freud in turn transformed the world. If ‘I’

is another, then this also affects modern science as it was inaugurated

by Descartes. In analysis—Lacan here refers to the psychoanalytic

experience—consciousness appears as “irremediably

limited” not unlike in Descartes. But in contrast to Cartesian

Rationalism, there is, in psychoanalysis, no perfect and infinite being

who would offset this limitation. Rather, God is unconscious, as Lacan

emphasizes (1981, 59). The discovery of the unconscious leads to the

realization that God is not the True. The Real that cannot be

assimilated is the True, and “the world […] struck with a

presumption of idealization” (81).

The realization that God is unconscious is one side of the scientific

character of psychoanalysis. It implies that at the center of our

experience is not the relation with an infinite and perfect being, but

the “relation […] with the organ” (1981, 91;

translation modified, M.H.) [5]—with the

breast, excrement, but also with the eye, among others. This authorizes

Lacan to compare the brush strokes of Matisse with the feathers a bird

lets fall.

The other side of the scientific character of psychoanalysis results

from a fact that Lacan also knows from the analytic experience: namely,

the Real “always comes back to the same place”—which

is precisely the place “where the subject in so far as he

cogitates, where the res cogitans, does not meet it”

(1981, 49; translation modified, M.H.).[6] Regarding the status

of psychoanalysis as a science, the decisive question is whether or not

this return—which is accidental and oscillates between hazard and

fortune—can be operationalized. In other words, it is a matter of

basing the randomness of this return of the Real on a scientific

foundation that is not deterministic. In this context, Lacan refers to

some of the most recent developments in the sciences of his

day—developments that “demonstrate,” as he puts it,

“what we can ground on chance.” Lacan is well aware that

first a limited structuring of the situation is required for this

purpose, a structuring “in terms of signifiers [ signifiants]” (40). By drawing on mathematical game

theory and cybernetics, Lacan is then able to reformulate

psychoanalysis as a conjectural science of the subject, and thus as a

technical discipline.

This reformulation of psychoanalysis proceeds in close contact with

clinical experience. Here, in psychoanalytic practice, consciousness

does not only appear as irremediably limited insofar as it is

instituted as a principle of idealization; it also manifests itself as

a principle of misunderstanding and misrecognition—or ofméconnaissance. Lacan also refers to this principle of méconnaissance as scotoma, a term used

to describe a partial loss of vision, a spot or, precisely, the gaze.

And it is, according to Lacan, this spot, this partial loss of vision,

this gaze, that Descartes failed to see when he saw the field of

knowledge “at the level of this vastest of subjects, the subject

who is supposed to know [le sujet supposé savoir],

God” (224; translation modified, M.H., 1990, 250).

Yet there are some who, according to Lacan, did see the strange

contingency in the geometral image—and thus in the image of

modern science and the geometral perspective it created: the painters

who were contemporaries of Descartes. As Lacan writes: painters,

“above all, have grasped this gaze as such in the mask and I have

only to remind you of Goya, for example, for you to realize this”

(1981, 84). Hence there is a certain complicity between painting and

psychoanalysis. Painting and psychoanalysis show that which the

geometral dimension elides. Or as Lacan puts it: “If one tries to

represent the position of the painter concretely in history, one

realizes that he is the source of something that may pass into the

real” (1981, 112).

In his interpretation of the slow-motion film of Matisse painting,

Lacan combines this cultural-historical justification with the

systematic legitimization of psychoanalysis as a conjectural science.

Using slow motion as a kind of magnifying lens for time, Lacan explains

that “the moment of seeing” ( l’instant de voir) can only appear as a suture

conjoining the Imaginary and the Symbolic (1981, 118). According to

Lacan, slow motion makes visible, in every moment of seeing, the

self-referential production of a “sort of temporal progress that

is called haste, thrust, forward movement” and hides the strange

contingency of the gaze (118). From this analysis, Lacan derives the

distinction between the gesture, which belongs to the Imaginary, and

the act, which pushes forward into the Symbolic. The brush stroke

appears as a movement that on the one hand terminates, and on the other

hand refers back. It is a motor activity that produces behind itself

its own stimulus: the gesture is hesitant. The act, by contrast, is

moving forward. According to Lacan, the act is projected forward as

haste in the identificatory dialectic of the signifier and the spoken.

It is nothing but the first moment of seeing, the Augenblick,

the moment of the creation of seeing. The act is the gesture in motion,

as Lacan writes, the gesture that is “shown to be seen”

(118). The gaze not only terminates the movement, it freezes it. This

arrest of the movement, its terminal moment, the interruption, is to be

understood, according to Lacan, as a mortification meant to dispossess

“the evil eye of the gaze” (118).

To return to the question of the place of the technical in the relation

between the aesthetic, knowledge, and the subject, we can say that

Lacan uses slow motion as an instrument. From the perspective of the

conjectural science of the subject, which is, for Lacan, a

technical science, the point of the instrument is to make visible that

which remains hidden from “human perception” and the

empirical sciences. For Lacan, it is not, as Merleau-Ponty maintained,

slow motion that deceives; rather, deception appears as the irreducible

end of gesture.

Not unlike Merleau-Ponty, however, albeit in a different manner, Lacan

also restores the body as a “sentinel” (Merleau-Ponty 1964a

160–1). In Lacan, the body functions as a guard who secures the

constitution of the subject in the experience of her central relation

to the organ. The construction of the subject proceeds, as Lacan

explains, by way of the gesture that materializes on the canvas with

the brush stroke and will “always [remain] present there”

(1981, 115). The trace of the organic left by the gesture on the

image—a trace, one might add, that points toward something human,

rather than something machinic—is nothing other than the

direction of the hand. According to Lacan, this trace of the organic is

responsible for the fact that one cannot laterally invert a technical

image—for instance, a diapositive—of a painted picture,

without its being immediately noticeable. Gesture—which Lacan

analyzed with the help of slow-motion technology—thus

becomes the stand-in for the alleged centrality of the relation between

the subject and the organ.

Gesture and the Technical

In conclusion, I would like to emphasize that the sentinels of

Merleau-Ponty and Lacan do not only protect thought from a flight into

metaphysics. They also prevent access to the question of what Walter

Benjamin termed in 1936 “a vast and unsuspected field of action [Spielraum]” that the age of reproduction had opened up,

through the camera’s technical pictures, the close-up, and its

use of slow motion (‘The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technical

Reproducibility’: 2nd version [1935], in Benjamin 2008, 37).

Although Merleau-Ponty and Lacan accentuate their critiques of the

philosophical tradition and the philosophy of the subject differently,

their references to the slow-motion film of Matisse make clear that

they both continue to think on the basis, and within the conceptual

framework, of this tradition. This philosophical tradition, however,

does not provide any concepts for the analysis of the

potential—and highly specific—productivity of the technical

that revolutionizes not only perception, but the very relation between

the subject and knowledge.

Probing this new room-for-play would require concepts of technicity and

mediality that allow one to think not only the historicity of

technology, but also the historicity of perception in its relation to

technology. In contrast to Merleau-Ponty and Lacan, Benjamin did not

equate technology with rationality. Instead, he outlined a philosophy

of technology, which related technology to the way we inhabit and

perceive the world and attempted at the same time to conceive of

perception as a medium. For Benjamin, film does not depict something,

nor does it show an artificial world; rather, it is the result of an

“intensive interpenetration” (intensive Durchdringung) of the apparatus and reality (2008,

35; 1985, 374). “The illusionary nature of film is of the second

degree. It is”, as Benjamin underscores, “the result of

editing” (35; 373). In this “nature of the second

degree” the human being is no longer at the center. Thus I would

like to conclude, not with Merleau-Ponty or Lacan, nor with the ethics

of gesture that Agamben has in mind, but with Benjamin’s proposal

to associate gesture with the technical. Benjamin removes gesture from

its association with the body or the organ. As I can only outline here,

he instead focuses his reflections on the artificial that links gesture

with the technical. The starting point of these reflections is

Brecht’s theater of gesture, which links gesture to distance,

alienation, and literarization—and thus in an explicit manner to

the increasingly technical nature of the lifeworld. Unlike the

Futurists, for example, Benjamin conceives of this link in terms of a

tender movement: the rhythm of the technical reappears in gesture as a

trembling.

In the first version of his manuscript “What is Epic

Theatre?” from 1931, Benjamin calls the epic theatre a

“literarized theatre” because of its use of posters and

lettering, but also because of its use of gestures, which relates epic

theatre to Chinese theatre. For Brecht according to Benjamin, in epic

theatre it is possible that an actor acts in front of the picture of

his character (such as a poster, a projection, an image). The result is

that we can no longer know which is the original and which is the copy,

what is real and what is performed. Benjamin discusses this approach to

epic theatre against the background of the question of how the relation

of the gesture to the situation should be understood. Now it must be

noted that ‘situation’ is nothing other than die Lage, which refers to the singular moment, the actual

presence. Benjamin answers this question by referring to the

“quivering” or “tremulousness of the contours”

of the back-projections, which, as he puts it, “suggest the far

greater and more intimate proximity from which they (the materialistic

ideas) have been wrenched in order to become visible” (Benjamin

1998, 12; see Weber 2008, 104). This “tremulousness of the

contours” is the medium in which the dialectics at standstill

enfolds (104).[7]

Now it is well known that Adorno (in his letter dated December 17 1934)

excitedly praised Benjamin’s essay on Kafka. Yet he disagreed

with Benjamin’s reference to epic theatre. His argument is

twofold. First, Adorno writes, Kafka’s novels cannot be regarded

as a script for epic theatre because they have no audience who could

directly intervene into the experiment. Secondly, he writes, the reason

why the gesture is important is not to be found in Chinese theatre, but

instead in modernity and in the dying away of language. From this he

concludes that Kafka’s novels are the last and vanishing textual

link to the silent movie. In other words, Adorno sees the ambiguity of

gesture situated between the sinking into silence with the destruction

of language and the rising of language in music. Though Benjamin

admitted that Adorno was right in his response, he nevertheless

referred to his original thoughts on the experimental character of

Kafka’s writings in his 1938 letter on Kafka to Scholem. There he

admits that Kafka lived in a “complementary

world” (1995 112; translation, M.H.)—that is to say,

Kafka’s experiments were in fact not addressed to an audience

that could intervene in the experiment. Nonetheless Benjamin holds on

to the idea that the gestures of Kafka’s figures are part of an

experimental process.[8]

Thus he states that Kafka’s gestures of horror benefit from

“the fantastic room-for-play, which the catastrophe will not

know” (1995, 112; translation, M.H.).[9]

The decisive word here is “fantastic room-for-play.” It

points back to the second version of the 1936 article on theWork of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility , in which Benjamin relates the turn from representation to

experimentation with what he calls second technology and second

technology with play.

Notes

[1] The French reads: “Nous l’avons reçu en plein

coeur. […] Je puis dire aussi que temps nous aura

manqué, en raison de cette fatalité mortelle, pour

rapprocher plus nos formules et nos énoncés” (Lacan

1991, 329).

[2] The French reads: “Or l’art et notamment la peinture

puisent à cette nappe de sens brut dont l'activisme ne veut

rien savoir” (Merleau-Ponty 1964b, 13).

[3] The passage reads:

Before my pencil ever touched the paper, my hand made a strange

journey of its own. I never realized before that I did this. I

suddenly felt as if I were shown naked—that everyone could

see this—it made me feel deeply embarrassed. You must

understand, this was not hesitation. I was unconsciously

establishing the relationship between the subject I was about to

draw and the size of my paper. (Bois 1990, 46)

[4] The French passage reads:

Au rythme où il pleut du pinceau du peintre ces petites

touches qui arriveront au miracle du tableau, il ne s’agit

pas de choix, mais d’autre chose. Cet autre chose, est-ce que

nous ne pouvons pas essayer de le formuler? Est-ce que la question

n’est pas à prendre au plus près de ce que

j’ai appelé la pluie du pinceau? Est-ce que, si un

oiseau peignait, ce ne serait pas en laissant choir ses plumes, un

serpent ses écailles, un arbre à s’écheniller

et à faire pleuvoir ses feuilles? (Lacan 1990, 129)

[5] The French reads : “Le rapport du sujet avec

l’organe est au coeur de notre expérience” (Lacan

1990, 105).

[6] The French reads “Le réel est ici ce qui revient

toujours à la même place—à cette place où

le sujet en tant qu’il cogite, où la res cogitans ne le

rencontre pas” (Lacan 1990, 59).

[7] The passage reads:

For as in Hegel, the sequence of time is not the mother of the

dialectic but only the medium in which the dialectic manifests

itself, so in epic theatre the dialectic is not born of the

contradiction between successive statements or ways of behaving,

but of gesture itself. (Weber 2008, 104)

[8] Benjamin compares Kafka’s literary procedure with gestures

with Arthur Stanley Eddington’s description of the world from

the perspective of the theory of relativity quantum theory in his

popular book “Weltbild der Physik”.

[9] The German reads: “Seinen Geberden des Schreckens kommt der

herrliche Spielraum zu gute, den die Katastrophe nicht kennen

wird” (1995, 112).

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. 1985a. Gesammelte Schriften. Vol. VI. Frankfurt:

Suhrkamp.

———. 1985b. Gesammelte Schriften. Vol. VII.

Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

———. 1995. Gesammelte Briefe. Vol. VI.

Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

———. 1998. “What is Epic Theatre?”. In Understanding Brecht, edited by Anna Bostock and Stanley Mitchell,

1–15. London: Verso.

———. 2008.

The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility and

Other Writings on Media. Edited by Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin.

Translated by Edmund Jephcott, Rodney Livingstone, and Howard Eiland.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bois, Yves-Alain. 1990. Painting as Model. Cambridge MA: MIT

Press.

Lacan, Jacques. 1981.

The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: The Four Fundamental Concepts of

Psychoanalysis. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. Translated by Alan Sheridan. Vol. XI. New

York: Norton.

———. 1990. Le séminaire, livre XI: Les quatres

concepts fondamentaux de la psychanalyse. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller.

Paris: Seuil.

———. 1991. Le séminaire, livre VIII: Le transfert: 1960–1961.

Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. Paris: Seuil.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1964a. “Eye and Mind.” In

The Primacy of Perception: And Other Essays on Phenomenological

Psychology, the Philosophy of Art, History and Politics, edited by James M. Edie, translated by Carleton Dallery, 159–92.

Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

———. 1964b. L’Oeil et l’Esprit.

Paris: Edition Gallimard.

———. 1964c.Signs. Translated by Richard

McCleary. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

———. 1964d. “The Film and the New

Psychology.” In Sense and Non-Sense, translated by Hubert L.

Dreyfus and Patricia Allen Dreyfus, 48–62. Evanston: Northwestern

University Press.

———. 1968. The Visible and the Invisible.

Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Roudinesco, Elisabeth. 1997. Jacques Lacan: Outline of a Life, History of a System of Thought.

Translated by Barbara Bray. New York: Columbia University Press.

Waldenfels, Bernhard. 1993. “Interrogative Thinking: Reflections on

Merleau-Ponty’s Later Philosophy.” In Merleau-Ponty in Contemporary Perspective, edited by Patrick V.

Burke and Jan Van der Veken, 129:3–12. Phaenomenologica. Dordrecht:

Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-1751-7_1

Wiesing, Lambert. 2000. “Merleau-Pontys Phänomenologie des

Bildes.” In Maurice Merleau-Ponty und die Humanwissenschaften, edited by

Regula Giuliani, 263–80. Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag.

Biography

Astrid Deuber-Mankowsky is Professor of Media Studies and Gender Studies at

the Ruhr University Bochum. She has published extensively on feminist and

queer theory, representation and mediality, media theory and philosophy as

well as religion and modernism. She was a visiting scholar at UC Berkeley

(2007), visiting professor at the Centre d'études du vivant,

Université Paris VII - Diderot (2010), Max Kade Professor at Columbia

University (2012), and Senior Fellow at the Internationales Kolleg für

Kulturtechnikforschung und Medienphilosophie (IKKM) Weimar (2013). She is

also an associate member of the Institute for Cultural Inquiry Berlin (ICI

Berlin).

© 2017 Astrid Deuber-Mankowsky

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The film begins with a female model clad in a bright, wide dress

entering Matisse’s studio—a space suffused with light. The

model sits down in an armchair, and the master adjusts her position and

arranges her dress a bit. Merleau-Ponty does not mention the gender

coding of the scene, while Lacan comments on it only indirectly, along

the lines of his psychoanalytic reading. At first, the scene unfolds at

the usual speed. The camera wanders from the model to the easel, before

focusing on the canvas and the hand of Matisse, who is holding a brush

and transferring the outlines of the face and the hair with a

succession of deliberate brushstrokes onto the canvas. The scene is set

to a movement with much forward momentum from César Franck’s

well-known symphony in D minor, and it is accompanied by a voice-over

that rushes forth in a similar manner. At the conclusion of the scene,

it is repeated, but this time it has been recorded at a much higher

frame rate and thus appears in slow motion when it is replayed at

normal speed. This shift is also marked acoustically by a change in

rhythm. As the voice-over comments, “grace au cinéma,”

thanks to the technology of cinema, one is able to analyze, in slow

motion, the gestures with which Matisse transfers paint onto the

canvas.

The film begins with a female model clad in a bright, wide dress

entering Matisse’s studio—a space suffused with light. The

model sits down in an armchair, and the master adjusts her position and

arranges her dress a bit. Merleau-Ponty does not mention the gender

coding of the scene, while Lacan comments on it only indirectly, along

the lines of his psychoanalytic reading. At first, the scene unfolds at

the usual speed. The camera wanders from the model to the easel, before

focusing on the canvas and the hand of Matisse, who is holding a brush

and transferring the outlines of the face and the hair with a

succession of deliberate brushstrokes onto the canvas. The scene is set

to a movement with much forward momentum from César Franck’s

well-known symphony in D minor, and it is accompanied by a voice-over

that rushes forth in a similar manner. At the conclusion of the scene,

it is repeated, but this time it has been recorded at a much higher

frame rate and thus appears in slow motion when it is replayed at

normal speed. This shift is also marked acoustically by a change in

rhythm. As the voice-over comments, “grace au cinéma,”

thanks to the technology of cinema, one is able to analyze, in slow

motion, the gestures with which Matisse transfers paint onto the

canvas.