Ethics, Staged

Carrie Noland, University of California, Irvine

In March 2016, I had the opportunity to attend three weeks of

rehearsals for the reconstruction of one of Merce Cunningham’s

most controversial works, Winterbranch, at the Lyon Opera

Ballet.[1] Winterbranch was choreographed for the Merce Cunningham Dance

Company’s first major tour and was first performed in New York,

just before the tour began, in 1964. It is a work that fell out of the

Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s repertory fairly early, perhaps

because it was too firmly connected not only to a particular phase in

the development of Cunningham’s aesthetic but also to the

particular historical moment known as “the 60s” when the

relation of art to context—especially political context—was

on everyone’s mind.[2] The Director of the

Lyon Opera Ballet conceived of the Ballet’s spring program as an

homage to the experimental dance of the 1960s; he chose to pair Winterbranch with Lucinda Childs’s Dance, a

bright, brisk, almost antiseptic minimalist piece from 1979 that

contrasts sharply with Cunningham’s somber, eery, and in some

ways more engaged minimalist work. Jennifer Goggans, a former

Cunningham dancer and presently an active reconstructor of his works,

arrived in Lyon in mid-March to begin training the dancers in

Cunningham technique. From the first day of rehearsals I was able to

watch her guide Lyon’s balletically trained, exquisitely skilled

dancers toward a performance of Winterbranch that, I believe,

remained faithful to its rebarbative, even gritty nature, despite the

unavoidable change in reception context.

As chance would have it—and when working on Cunningham one is

always attentive to chance—while attending the rehearsals at the

Lyon Opera I was also working on a paper for a conference on the ethics

of gesture, organized by the editor of this volume, Lucia Ruprecht; a

conference that would center on questions raised by Giorgio Agamben in

his famous essay, “Notes on Gesture” (2000, 49–59;

1996, 45–53). Naturally, my two objects of study— Winterbranch and the ethics of gesture—began to enter

into dialogue. The juxtaposition encouraged a comparison between

Agamben’s and Cunningham’s respective approaches to the

semiotics of dance, the way that dance can generate meaning but also

evade meaning in a way that Agamben deems “proper” to the

“ethical sphere” (2000, 56). For Agamben, dance is composed

of what he calls “gestures” that have “nothing to

express” other than expressivity itself as a “power”

unique to humans who have language (“Languages and

Peoples”) (2000, 68). For Cunningham, dance is composed of what

he calls “actions”, or at other times

“facts”—discrete and repeatable movements sketched in

the air that reveal the “passion,” the raw or naked

“energy” of human expressivity before that energy has been

directed toward a specific expressive project (1997, 86). I will look

more closely at what Cunningham means by “actions,” and to

what extent they can be considered “gestures” in

Agamben’s terms; I will also explore the “ethical

sphere” opened by the display of mediality, the

“being-in-a-medium” of human beings (“The

Face”) (2000, 57). But for the moment I want simply to note that

for both, dance involves the exposure on stage of an energy or, in

Agamben’s terms, a “power” (potere)

(“The Face”) (2000, 95), that derives from the

fundamentally “communicative nature of human beings,” their

“linguistic nature” (“Languages and

Peoples”) (2000, 68).[3] In addition, the

exposure of this communicative energy as energy has, for both,

important emancipatory, even utopian implications. That said, the

choreographer and philosopher understand the ethics of dance in

slightly different terms. The following essay constitutes my effort to

understand how these terms differ. I seek to clarify what Cunningham

shares with Agamben’s neo-phenomenological approach to gesture

but also the nuance he brings to the philosophical table as a

choreographer—that is, as someone who works through and with

movement as a theoretical tool.

Few scholars have been attentive to Agamben’s interest in dance

per se. This may be because Agamben’s interest in dance is

motivated neither by a deep knowledge of dance history nor by a

fascination with the work of a particular choreographer.[4] Rather, his interest

stems from an intuition that danced gestures throw into relief what is gestural in the gesture, its “media character”

(2000, 57)—and mediality, as we shall see, ensures the ethical,

or relational sphere of the human. Likewise, in the parallel universe

of dance studies, very little has been written on Winterbranch

as a study of gesture, although it has been recognized that, perhaps

more than most of Cunningham’s dances, Winterbranch

solicits on the part of the audience the act of interpretation, that

is, its gestures appear to spectators as charged with specific

meanings. Indeed, if there is a dance in Cunningham’s repertory

that conjures an ethical sphere, it is Winterbranch.

Juxtaposing Winterbranch with Agamben’s writings on

gesture allows for an exploration of critical theory through a specific

example of choreographic practice. Such a juxtaposition urges us to

question precisely what a dance gesture is, and whether gesture is in

essence an exposure of “communicability itself” (Agamben

2000, 83). What do dance gestures expose that ordinary gestures do not?

Why would such an exposure be “ethical” in Agamben’s

terms? And why would (his notion of) the ethical rely on a stage?

Part I: Agamben on Gesture

The first thing one notes when approaching Agamben’s “Notes

on Gesture” is the fluidity or vagueness of the term

“gesture.” By “gesture” Agamben does not

necessarily mean a communicative gesture, such as a thumbs up or a hand

extended. Nor is he talking about functional gestures à la

Leroi-Gourhan—elements of a chaîne opératoire

or a “habitus.”[5] Instead, I think

Agamben is getting at a larger category of gestures that, at least in

their familiar, non-spectacular contexts, disclose a project or an

intention (to use a Sartrean vocabulary), gestures that are part of an

“intentional arc” (Merleau-Ponty’s term), that

“always refer beyond” themselves “to a whole”

of which they are “a part” (Agamben 2000, 54).[6] This category

includes locomotion, which is not traditionally understood by dancers

as gestural. Rudolf Laban, for instance, considered

“gestures” to be an affair of the upper body and separated

them from “steps.” “Steps,” constitute a large

group encompassing all one can do with the feet—advance,

turn, hop, leap, and so on, whereas a “port-de-bras” and an

“épaulement” are gestures in Laban’s sense of

the term (see Laban 1960).

In contrast, Agamben appears to believe that dance—in its

totality—is the ultimate gesture. In “Notes on

Gesture,” he asserts that dance “exhibits” in

exemplary fashion what is gestural in the gesture: “If

dance is gesture, it is so, rather, because it is nothing more than the

endurance and the exhibition of the media character of corporal

movements” (57). “The gesture,” he

italicizes, “is the exhibition of a mediality: it is the process of making a means visible as such”

(57). Dance, it would appear, distills, in aestheticized, heightened

form what the essence of gesture is, namely, a medium that

exposes itself as such. But how does a medium expose itself as such?

What is it in dance that allows it to be the site of such an

exhibition?

To begin to answer this question, we need to refer to a lesser known

essay that, to my knowledge, has only appeared in a French version,

“Le Geste et la danse.”[7] The essay reiterates

certain passages found in “Notes on Gesture”—it was

published the same year, 1992—while emphasizing different terms.

Here, gesture appears as a kind of power (in French,

“pouvoir” or “puissance”), a power of

“expression.” Linking the two essays, Agamben writes that

the most precise definition he can give of the “pouvoir du

geste”—or the power that is gesture—is the

power to expose itself as “pure moyen” (pure means).

“Ce qui dans chaque expression, reste sans expression,” he

underscores, “est geste” (That which in each act of

expression remains unexpressed is gesture) (12). Another way to say

this would be that gesture, in its ideal state (before being

subordinated to what Agamben calls elsewhere “a paralyzing

power”) is the embodiment of a force or “dynamis

” (2000, 55, 54). Gesture is the medium of movement; it

is movement as a medium, a kind of kinetic surface of

inscription, as opposed to other media or supports, such as the painted

image or the written word. Gesture exhibits the movement that is mediality—crossing over, traversing space,

connecting points, communicating.

Insofar as gestures move, are themselves movement, they represent for

Agamben the very opposite of the static image. In Means Without End, the static image is associated with all

that is “stiffened” or hardened—an

“image” (“Notes on Gesture”), a

“character” (“The Face”), or a

“spectacle” as commodity (“Marginal Commentaries on The Society of the Spectacle”) (2000). In

contrast, gesture is associated with all that is dynamic,

fluid—in short, mediamnic, understood as both

support and in-between, intervalic.[8] In his essay

“The Face,” for instance, the “face” plays the

same role as gesture; it is a “revelation of language

itself.” “Such a revelation,” he proposes,

“does not have any real content and does not tell the truth about

this or that state of being, about this or that aspect of human beings

and of the world: it is only opening, only communicability. To walk in

the light of the face means to be this opening—and to

suffer it, and to endure it” (2000, 91). In contrast, a

“character” is produced when the face

“stiffens,” when it must protect itself from the

vulnerability, the openness and lack of finitude that is its nature

(96). The “face” is thus like gesture, which also

“suffers” and “endures,” or which is

the process of suffering or enduring one’s medial character,

one’s existence as a surface or support of communication.

As has been noted, Agamben’s understanding of the ethical is very

close to that of Emmanuel Levinas, whose chapter “Ethics and the

Face” (1979) is clearly an important influence on many of the

essays in Means Without End. Levinas maintains here that the

ways in which human beings appear to one another (their

“face,” but also all signifying surfaces and supports) are

necessarily flawed; they communicate a message about the person, but

they also hide what cannot be communicated, what is not exhausted in

the act of communication. The “face” both exposes and

betrays; it is “proper” and “improper” (Agamben

2000, 96–7). The exposure of this insufficiency or impropriety in

the signs that bear us is itself an ethical—even a

“political”—act, for it implies that what is known of

the human is never complete, that human mediality—our capacity to

become sign—is endless: “The task of politics is to return

appearance itself to appearance, to cause appearance itself to

appear” (“The Face”) (2000, 94). Agamben mirrors

Levinas when he writes in “Kommerell, or On Gesture” that

one gestures at the point where language appears “at a

loss” (1999, 78). Other essays in Means without End make

a similar point from a more politicized angle. For instance, in

“Marginal Notes on commentaries on the Society of the Spectacle,” Agamben is concerned with the

means and relations of production that prevent such an exposure of

“loss.” He describes capitalist modes of spectacle that

reduce gestures to flat, immobilized appearances severed from the

unpredictable continuum of intentions that once animated them.

Gestures, he claims, have become pure image; they appear on a screen,

limitlessly appropriable, combinatorial. If “Marginal

Notes” is concerned with the spectacularization of gestures,

Agamben presents the opposite scenario in “The Face” and

“What is a camp?” Here, in the fascist version of the same

predicament, the human being is seized as raw life lacking the capacity

to become image, to become something legible in the currency of the other (114–5). The human

being is reduced to pure self-identity, incapable of circulating as a

sign, and thus no longer a “being-in-a-medium”—no

longer human—at all. Thus, if in “Marginal Notes,”

the danger is that human beings will be reduced to pure surface,

“stiffened” into a circulating sign or commodity form, in

“The Face” and “What is a camp?” the danger is

that human beings will be robbed of that very surface-generating

capacity: they will be seized as “nature” tout court and thus deprived of their “linguistic nature,” their “mediality.”

In this context we should recall that for Agamben gesture is always

related not simply to the act of bearing but also, like the face, to

the process of exposing, or exhibiting. The Italian terms Agamben

employs are “esporre”—which means both

“express” and “exhibit” and

“esibizione,” a “show,” “display,”

or “performance” (1996, 52–3, 51). We can begin to

understand why Agamben privileges gesture, and dance gesture in

particular. As movement, gesture exceeds dynamically its signifying or

operational functions. It is highly visible—kinetically and

optically—and thus ideal for “making a means visible as

such.” Agamben’s examples of the gesture include ambulation

(the gait), Warburg’s pathosformel (or dynamograms) (1999, 89–103), the mime gestures of the

Commedia del’Arte (1999, 77–85), “everyday

gestures” (1999, 83), and of course dance gestures, or dance as a

series of gestures. Speech, too, can be gestural, just as there is in

gesture something of speech. As he insists, gesture “is not an

absolutely non-linguistic element,” it points to that

“stratum of language that is not exhausted in communication...” (1999, 77; my

emphasis). In all these cases, what makes gesture gesture is that it

carries something forward that is not equivalent to, or reducible to,

sense. As Agamben stresses, gesture “has precisely nothing to

say” (2000, 58).[9]

To expose this gestural quality of the act of communication—which

is not exhausted by semantics—is to open the

“ethical dimension” (2000, 57). The fact that many of his

examples of gestures capable of opening that ethical dimension are

those that occur on stage suggests the degree to which exposing relies

on performing. Twice-behaved behavior, gestures on stage, exemplify the

act—in both the practical and theatrical senses of the

word—that “cause[s] appearance itself to appear”

(2000, 94).

Part II: From the Ethics of Gesture to the Ethics of Dance

But why does dance embody that act of exposure par excellence? What are

the ethics—or, in another version, the politics—of the

gesture that is dance?[10] Let us recall that

dance enters Agamben’s account at precisely the moment when

“human beings [...] have lost every sense of naturalness,”

when they have “lost [their] gestures” (2000, 52). Despite

the emerging domination of capitalist relations which

“stiffen” gestures, dance remains an instrument of

liberation, or at least a form of critical nostalgia for a time when

gestures were both natural and under the subject’s control. If,

by the twentieth century, an entire generation has “lost its

gestures,” then how is it that the gestures of dancers have

managed to escape this pathological condition?

A glance in the direction of Agamben’s source for his

understanding of dance (and its relation to historical periods) might

help us answer this question. Agamben may very well have been

influenced by the work of Susanne Langer, whose Feeling and Form of 1953 was one of the first important

philosophical treatments of dance. Agamben seems to refer indirectly to

Langer’s book when he turns to dance in “Notes on

Gesture”:

The dance of Isadora Duncan and Sergei Diaghilev, the novels of Proust,

the great Jugendstil poetry from Pascoli to Rilke, and,

finally and most exemplarily, the silent movie trace the magic circle in which humanity tried for the last time to

evoke what was slipping through its fingers forever. (2000, 52–3;

my emphasis)

The phrase “the magic circle” is one that Agamben might

have borrowed from Langer, who in turn borrowed it from a text by Mary

Wigman (Langer 1953, 188–207).[11] Langer in fact

titles a chapter “The Magic Circle,” referring to what Curt

Sachs hypothesized was the oldest dance form, the circle dance (1953,

190). Within this circle, human beings first recognized the

“terrible and fecund Powers that surround” them and that

enter their very bodies, transforming them into a source of movement

power (196). Basing much of her argument on Sachs, Langer describes the

“magic circle” as implicit in all forms of dance, both

“primitive” and contemporary. Today, secular or ballroom

dance, she states, “enthrall the dancer almost instantly in a

romantic unrealism,” whereas “primitive” dance

achieves the ecstatic “by weaving the ‘magic circle’

around the altar of the deity, whereby every dancer is exalted at once

to the status of a mystic” (196). What Langer calls

“virtual gesture”—meaning gesture that has been

lifted out of its “common usage” and placed on the

stage—is “the appearance of Power” (52, 198). Dance

exhibits the “magnetic forces that unite a group” when

dancers exhibit this “Power” as such (202).

Agamben might have called on Langer’s (and Sachs’s) notion

of the “magic circle” to evoke a break between a pre-modern

and a modern relation to gesture. Like Agamben, Langer also maintains

that a loss has occured. In modernity, although the “magic around

the altar” has been broken, modern dance in particular is still

animated with that “Power,” it is still serving the same

function (207). However, she qualifies, “we”—the

moderns—”evoke [that same Power] with full knowledge of its

imaginary status” (206). Langer’s words help us understand

why Agamben strings together turn-of-the-century dance (e.g.,

“Duncan and Diaghilev”) with Proust and Rilke, for they

share—at least according to Agamben—a nostalgia for an

experience that has moved from the realm of ritual communion to the

realm of the stage (an “imaginary status” [206]). However,

Agamben departs from the type of primitivist rhetoric that Langer could

be accused of perpetuating when he insists that gesture contains a

linguistic element, that it is “closely tied to language,”

to “the stratum of language that is not exhausted in

communication” (1999, 77).[12] Presumably, then,

dance would not be any more primitive than language itself; and yet, as

visibly and undeniably movement, it promises to expose more

dramatically that which moves in language, the inexhaustible

“stratum” that language is “at a loss” to

convey. It is perhaps for this reason that in “Le Geste et la

danse,” instead of evoking what has been irrevocably lost, dance

exemplifies what is not lost—at least not to

dance—that which dance alone can continue to exhibit, namely, the

human potential to be a “milieu pur” (2000, 57). [13] Agamben presents

concert dance in particular as the last refuge of

“communicability”: “Ce qui dans chaque expression, reste sans expression, est

geste. Mais ce qui, dans chaque expression, reste sans expression,

c’est l’expression elle-même, le moyen expressif en

tant que tel” (That which in each act of expression remains without expression, is gesture. But that which, in each expression, remains without

expression, is expression itself, the means of expression as such).

Dance gestures, it would appear, are a hypostatized form of gesture, or

the gestural; they evoke that “Power” (Langer) to express a

world, to have a world, the “Power” that is our

“linguistic nature” and that holds us within the

“magic circle” of the human. Sounding much like Langer,

Agamben concludes “Le Geste et la danse” by affirming that

“la danse des danseurs qui dansent ensemble sur une scène

est l’accomplissement de leur habilité à la danse et de

leur puissance de danser en tant que puissance” (the dance of

dancers who dance together on a stage is the accomplishment of their

skill in dancing and their power to dance as power) (12; my

emphasis).

It is not clear to me that in “Le Geste et la danse”

Agamben has provided a convincing portrait of dance, or that he has

revealed its nature as a gestural form “closely tied to

language” (not “not linguistic”) (1999, 77;

my emphasis). In his treatment, dance retains too much of its relation

to a primitive, pre-verbal world of ritual, even if only from the

perspective of a modernist “imaginary.” What is perhaps

more useful for our purposes—especially as we move toward a

reading of Winterbranch—is Agamben’s account of how the gesturality of the gesture is exposed, that is, how

“le moyen expressif en tant que tel” (the means of

expression as such) might be made to appear. Ironically, in

“Notes on Gesture” he associates such an appearance or

display with the act of interruption, not with the fluid

movements of the dancer, bathing blissfully in the “milieu

pur” of a “power to dance as power.” To close this

part of my argument, and to prepare for my reading of Winterbranch, let us return briefly to a passage in which

Agamben takes up the example of the pornographic, the gestures of which

can be suspended, he argues, to reveal their intrinsic and irreducible

“mediality”:

The gesture is the exhibition of a mediality: it is the process of

making a means visible as such

[original emphasis]. It allows the emergence of the being-in-a-medium

of human beings and thus it opens the ethical dimension for them. But,

just as in a pornographic film, people caught in the act of

performing a gesture that is simply a means addressed to the end of

giving pleasure to others (or to themselves) are kept suspended in and by their own mediality—for the only

reason of being shot and exhibited in their mediality—and can

become the medium of a new pleasure for the audience (a pleasure that

would otherwise be incomprehensible) [my emphasis]... so what is

relayed to human beings in gestures is not the sphere of an end in

itself but rather the sphere of pure and endless mediality. (2000,

57–8)

I would like to keep in mind this scene as we move forward, one in

which the ethical dimension appears to open within the pornographic,

one in which something “pure” and without end is captured

in a filmed act that obviously has a very concrete end. As opposed to

his brief excursus on dance, which confuses dancing with an

uninterrupted “magic circle,” Agamben’s comments on

film (and the pornographic film in particular) allow us a firmer

purchase on what dance, as a form of gesture, might be—and what

it might be able to accomplish, or expose. Here, also, instead of

indulging in the fantasy of the “en tant que tel” (as

such), and the “moyen pur” (pure means), Agamben suggests,

albeit obliquely, that a means is never pure, that it can in fact never

be exposed as “an end in itself,” and that the means is

itself mediated by what it bears. That is, it is mediality

only insofar as it is actively mediating.

In sum, what is interesting and revealing about this passage on the

pornographic film is that, as in “The Face,” Agamben opens

the ethical dimension not at the point where communication is lost, but

rather at the point where saying “something in common” (the

clearly legible pornographic gesture) and saying “nothing”

(the gesture interrupted, exposed as a gesture) occur simultaneously

(“Form of Life”) (2000, 9). He points us toward that

ambiguous point where a narrative unfolds and yet that narrative is

suspended, revealing a “stratum” “not

exhausted” by a narrative (1999, 77), a point where the

communication is interrupted, yet still “endured.”.

I believe that it is in this type of

suspension—understood as a medium—that Agamben’s

ethics of gesture resides. In the next section I will argue that it is

in this type of suspension that we might discover Cunningham’s

ethics of gesture as well.

Part III. The Cunningham Gesture

As is well known, Cunningham often expressed his intention to create

dances that would not impose a particular interpretation on his

audience: “We don’t attempt to make the individual

spectator think a certain way,” he stated in a 1979 interview:

“I do think each spectator is individual, that it isn’t a public. Each spectator as an individual can receive what we

do in his own way and need not see the same thing, or hear the same

thing, as the person next to him” (Cunningham and Lesschaeve

2009, 171–2).[14]

Earlier, in 1968, Cunningham had already advanced a similar view: dance

“can and does evoke all sorts of individual responses in the

single spectator” (1968, n.p.). “Any idea as to mood,

story, or expression entertained by the spectator is a product of his

mind, his feelings” (1970, 175).

As is well known, Cunningham often expressed his intention to create

dances that would not impose a particular interpretation on his

audience: “We don’t attempt to make the individual

spectator think a certain way,” he stated in a 1979 interview:

“I do think each spectator is individual, that it isn’t a public. Each spectator as an individual can receive what we

do in his own way and need not see the same thing, or hear the same

thing, as the person next to him” (Cunningham and Lesschaeve

2009, 171–2).[14]

Earlier, in 1968, Cunningham had already advanced a similar view: dance

“can and does evoke all sorts of individual responses in the

single spectator” (1968, n.p.). “Any idea as to mood,

story, or expression entertained by the spectator is a product of his

mind, his feelings” (1970, 175).

Cunningham’s resistance to conventional plot-lines and

psychological interpretations is well known. Influenced, as was John

Cage, by the reception theory of Marcel Duchamp, Cunningham aimed to

address—and thus create—a spectator who would

“complete” the work (see Duchamp 1975). This was in large

part a reaction against what he saw around him in the dance of the

1940s: “It was almost impossible,” he wrote in 1968,

“to see a movement in modern dance during that period not

stiffened by literary or personal connection” (1968, n.p.; quoted

in Vaughan 1997, 69). In an effort to avoid imposing literary or

personal connections, Cunningham developed a set of procedures that

would ensure, at least in principle, that his own intentions, his

“personal connections,” would not shape or

“stiffen” the movement material. Since many compositional

decisions would be taken out of his hands, he could with some

justification insist that meanings generated by viewers were theirs

alone. Some critics took this to mean that there was no expressive

content to his dances.[15] John Martin wrote

in a dismissive review of 1950 that there is “little in content

and nothing of conspicuous formal value” in Cunningham’s

dances (1950, 69) while Doris Hering lamented in 1954 that his chance

compositions were like “tired utterances suspended in an

emotionless void” (1954, 69). And yet Cunningham was quite clear

on this point: his goal was not to suppress the expressivity of his

dancers but quite the opposite, to intensify that expressivity, to

expose on stage not “anger” or “joy,” but

rather what he called the pure undifferentiated “source of energy

out of which may be channelled the energy that goes into the various

emotional behaviors” (1952; reprinted in Vaughan 1997, 86).

“Dance is not emotion, passion for her, anger against him.

[…] In its essence, in the nakedness of its energy it is a source

from which passion or anger may issue in a particular form” (86; my emphasis).

Here, Cunningham seems to anticipate Agamben, defining dance as a

movement form that displays “the nakedness” of an

“energy” drawn from “common pools of motor

impulses” (in Vaughan 1997, 86), impulses presumably shared by

human beings moving within the magic circle of communicability. But

Cunningham also takes care to acknowledge the “particular

form” in which that energy is exposed. For that reason, the

“nakedness” to which he refers is not reducible to the

purity evoked by the phrase “milieu pur” that Agamben

borrows from Mallarmé.[16] There is in fact

something almost pornographic about Cunningham’s

“nakedness,” “that blatant exhibiting of this

energy,” as he puts it (in Vaughan 1997, 86). As I have argued

elsewhere, Cunningham engages in an erotics of the

not-quite-abstracted; he is keen to exhibit the dirt—the literal dirt, as we shall see in the case of Winterbranch—that clings to the movements of dancers

like a semantic residue weighing them down (see Noland 2017). What

makes Winterbranch a particularly interesting case to study in

this regard is that the gestures the dancers perform are at once

legible and inscrutable, related to specific operational and expressive

tasks and yet disaggregated, distorted, interrupted. One could say that Winterbranch practices an ethics of gesture insofar as it

suspends movement between an “impure” manifestation

(“passion for her,” “anger against him”) and

raw human kinesis imagined as a “pure” support. Put

differently, the dance seems to play on the fine line between a

“naked” and a “channelled” energy, between a

“source” of emotion and emotion in a “particular

form” (in Vaughan 1997, 86). While remaining mysterious and

illegible, Winterbranch nonetheless inspires the act of

interpretation, the search for meaning, and thus the attribution to

movement of expressive content. During the 1960s and 1970s audience

interpretations invariably indexed the sinister, even apocalyptic tone

of the piece and the task-like nature of the movement content. But just

what is this movement content and to what extent can it be considered

gestural?

One of the obstacles we face when moving from philosophy to

choreography, from Agamben to Cunningham, is lexical in nature.

Cunningham uses many terms to refer to what Agamben calls the

“gestures” of dance: “actions,”

“facts,” “movements,” and

“gestures.” He often has recourse to the word

“gesture” to refer to the “ordinary” gesture

one finds in the street, task-related gestures (such as potting a

plant),[17] and even

“intimate gesture[s]” that convey a feeling (Cunningham and

Lesschaeve 2009, 106). Speaking of Signals (1970), for

instance, he notes that a movement of one of his dancers suddenly

struck him as an “intimate gesture,” although he had not

intended it to be so (106). The particular combination of dancers and

the particular place the movement appeared in the sequence made it look

like a gesture of intimacy shared between partners: “you

don’t have to decide that this is an intimate

gesture,” Cunningham states, “but you do something, and it

becomes so” (106; my emphasis). This tells us something about

Cunningham as an observer (rather than a creator) of gestures:

he is able to acknowledge the evocative—even conventionally

expressive—quality of a danced gesture. Moreover, as the anecdote

suggests, he is interested in that evocative gesture,

especially if it suggests a relationship (and thus a scenario or

drama). For him, a movement has the status of a gesture when it is

eloquent of a relation (whether “found” or developed by the

dancers), or when, alternatively, it mimes or actually completes a

specific task. In sum, the word “gesture” in

Cunningham’s vocabulary references both a task-like,

“ordinary” movement and an expressive movement.

Cunningham recognizes that gestures have a signifying dimension insofar

as they are part of a culturally legible situation.

Yet “gestures” are simultaneously technical building

blocks, movements to be placed in an array and thus removed from the

contexts in which they either say something (in a system of meaning) or

do something (in a habitus). The purpose of the grids, lists,

and chance procedures that Cunningham developed over the course of his

career was to reveal through recombination new local contexts in which

decontextualized human actions might be viewed. Cunningham puts it this

way in Changes: “you do not separate the human being

from the actions he does, or the actions which surround him,

but you can see what it is like to break these actions up in

different ways” (1968, n.p.). To “break up” an action is to

interrupt it. It is to expose the modality of movement, the tonus or

type of effort supporting the intention. In short, to “break

up” an action is to seek contact with the “nakedness”

of an energy underlying “passion for her [...] anger against

him” (1952; reprinted in Vaughan 1997, 86). It is to interrupt

the flow of gestures, to expose the support that gesture is—in

Agamben’s terms—that gesture is as such. It is

also, as Cunningham puts it, to take the ground away from beneath the

feet of the spectators, to shift them toward an “abyss”

where conventional associations no longer function:

I think that dance at its best [...] produces an indefinable and

unforgettable abyss in the spectator. It is only an instant, and

immediately following that instant the mind is busy [...] the feelings

are busy [...] But there is that instant, and it does renew us.

(Cunningham in Dalva ed. 2007, n.p.)

The question remains, though, whether such suspension over an

“abyss” opens the ethical dimension or whether instead that

dimension opens as one crosses the abyss, in an interval that

also promises connection. Winterbranch is a study of what

happens when one “breaks up” an action—in this case,

the action of falling. A fall can be broken, cinematically interrupted,

but a falling body inevitably lands.

Part IV. Falling in Winterbranch

Winterbranch

dates from a phase in Cunningham’s career when he was less

interested in incorporating “ordinary gestures” than in

investigating what the fundamentals of a dance vocabulary might be.[18] In the early

1960s, he began to focus on what he called “facts in

dancing”: “I have a tendency to deal with what I call the

facts in dancing,” he explained to David Vaughan, his archivist

(Vaughan 1997, 135).[19] Influenced,

perhaps, by the Classical Hindu Rasa theory of the “eight

permanent emotions,” he sought to reduce his vocabulary to a set

of eight essential movement varieties, without, however, attaching any

particular emotive value to them. We find in the “Choreographic

Records” for Crises (1960), for instance, the following

list: “Bend /Rise /Extend /Turn /Glide /Dart /Jump /Fall”

(box 3, box 11, Cunningham, n.d.). After identifying these eight

“facts,” the choreographer then declined them into

sub-categories, thus exploring systematically the anatomical

possibilities of the human body. Here, Cunningham exemplifies the

“materialist” sensibility of John Cage and the composers of

“la musique concrète” who maintained that the

materials of a craft could be enumerated in a non-hierarchical,

a-semantic taxonomy with no reference to their value in a harmonic

system. In Cunningham’s “The Impermanent Art” we hear

an echo of Cage’s aesthetics as they are presented in

“Lecture on Something” (1959). Cage: “each something

is really what it is.” Cunningham:

A thing is just that thing […]. In dance, it is the simple fact

of a jump being a jump, and the further fact of what shape the jump takes my emphasis]. This attention given

the jump eliminates the necessity to feel that the meaning of dancing

lies in everything but the dancing, and further eliminates

cause-and-effect worry as to what movement should follow what movement,

frees one’s feelings about continuity, and makes it clear that

each act of life can be its own history: past, present and future, and

can be so regarded, which helps to break the chains that too often

follow dancers’ feet around.” (Reprinted in Vaughan 1997,

86)

For Winterbranch, Cunningham chose to focus not on the

“jump” but rather on the “Fall.”[20] The dance is

composed of eighteen sections, each of which centers on a different way

of falling (Winterbranch “Choreographic Records,”

Cunningham, n.d.). However, when he writes in the passage above that

the “simple fact of a jump” is complicated by a

“further fact”—namely,” “what shape the

jump takes”—he departs from a strict Cagean materialism.

That the first “fact” has to be accompanied by a

“further fact” (a movement has to be realized by a

particular person in a particular sequence) indicates that the

categories of movement themselves are “facts” only in a

virtual sense. That is, they exist as classes of physical action to be

actualized in a particular phenomenalized “shape.” Even in

a classroom exercise,, “a “Bend,” for instance, is

contoured by the movement that comes before and the movement that

follows; “a “pré-mouvement,” as Hubert Godard

terms it, anticipates and orients what will come next (Ginot and Marcel

eds. 1998, 224–9). That is why the movement’s place in a

sequence is so vital to the manner in which it will be performed, and

thus to the manner in which it will strike the eye. Just as the

“fact” of extending a hand to the sternum of one’s

partner might, as in Signals, become “a

“gesture” recognized as “intimate,” so too a

“Bend” “Twist,” or “Fall” might be

phenomenalized as a gesture resonant with expressive, dramatic, even

semantic force when executed in a particular sequence by a particular

dancer and under the unique conditions of a theatrical performance. As

Jill Johnston wrote succinctly in 1963, in a Cunningham dance

“the gesture is the performer; the performer is the

gesture” (10).

Thus, what Cunningham calls “the attention given the jump”

excludes neither his interest in nor his desire to solicit the input of

the individual dancer. On the contrary, such attention (cultivated in

the dancer as well) allows each one to discover and reveal his or her

singularity: “from the beginning I tried to look at the people I

had, and see what they did and could do... You can’t expect this

one to dance like the other one. You can give them the same movement

and then see how each does it in relationship to himself, to his being,

not as a dancer but as a person” (Cunningham and Lesschaeve 2009,

65).[21] Especially

during the 1950s and 1960s, Cunningham was acutely attuned to the

movement qualities as well as the personalities of his dancers. In

fact, he often began the choreographic process by compiling “a

“gamut” of movements—one gamut for each

dancer—that would serve as the fundamental movement vocabulary

for the piece, thus taking full advantage of the unique

“shapes” each dancer tended to make when actualizing the

dancing “fact.”

However, Winterbranch is concerned less with highlighting the

qualities of a particular dancer than with the “Fall,” one

of the eight movement “facts” on Cunningham’s list.

Cunningham explained to Jacqueline Lesschaeve that he “wanted to

make a dance about falling” (Cunningham and Lesschaeve 2009,

101). So, quite simply, he “worked on falls” (101). first

alone in the studio and then with the dancers he had in the Company at

the time: Carolyn Brown, Viola Farber, Barbara Lloyd, William Davis,

and Steve Paxton. In his account of the work he insists repeatedly that

his main interest was in “the idea of bodies falling,”

resisting the implication—made by Lesschaeve and

others—that he had any other message in mind (Vaughan 1997, 137).

While admitting that the dance caused “a “furor”

whenever it was performed, he remains coy in the Lesschaeve interview,

acknowledging but never validating the strong reactions to which it

gave rise:

In Sweden they said it was about race riots; in Germany they thought of

concentration camps, in London they spoke of bombed cities; in Tokyo

they said it was the atom bomb. A lady with us took care of the child

[Benjamin Lloyd] who was on the trip. She was the wife of a sea captain

and said it looked like a shipwreck to her [...]. Everybody was drawing

on his own experience, whereas I had simply made a piece which was

involved with falls, the idea of bodies falling. (Vaughan

1997, 135, 137)

Carolyn Brown, who danced in Winterbranch throughout the 1964

tour, writes in her autobiography Chance and Circumstance that

“In Germany, interestingly, no one thought to liken Winterbranch to the Holocaust, although this happened

regularly in other European countries” (2007, 389). Meanwhile,

the reviewer for the London Times wrote that “Winterbranch is a disturbing work [...] The dancers, dressed

in all-over black like wartime commandos, writhe and grope their way

through gloom” (1964, 4). After a New York performance in 1967

Don McDonagh commented that Winterbranch had been

“variously interpreted as a plea for civil rights and a

shipwreck” (1976, 289). And Arlene Croce, reviewer for Ballet Review, wrote that “Winterbranch seems

to me a pre-vision of hell” (1968, 25).[22] But whether

critics identified Winterbranch with Auschwitz, the

battlefield, or hell, they all remarked on what Brown calls “the ethos of Winterbranch; darkness, foreboding, terror,

devastation, alienation, doom” (2007, 477).

Before proceeding to a closer analysis of the movement content of Winterbranch, we need to recall both the artistic and the

political contexts of the work. With respect to the artistic context,

Cunningham was in the process of assimilating developments in the New

York dance scene, developments that—at least for a short

period—caused him to rethink his dance vocabulary. Members of the

Judson Dance Group, including Yvonne Rainer, Simone Forti, and Trisha

Brown, started incorporating everyday and task movement into their

works as early as July 1962 (see Banes 1993). Simultaneously, the

“Junk Art” and Fluxus movements of the 1960s encouraged the

incorporation into performance and exhibition spaces of urban detritus

and industrial waste.[23] Winterbranch reflects both these trends. Further, the

directions that Cunningham gave to his Artistic Director of the time,

Robert Rauschenberg, reveal the influence on his work of his own

personal experience. These directions are particularly precise, more

detailed and explicit—and thus constraining—than Cunningham

typically supplied. He even republished in Changes: Notes on Choreography elements of the letter he wrote

to Rauschenberg in which he outlines his preferences for décor and

lighting:

The lighting is done freely each time, differently, so that the rhythms

of the movements are differently accented and the shapes differently

seen, partially or not at all. I asked robert rauschenberg [sic] to

think of the light as though it were night instead of day. i

don’t mean night as referred to in romantic pieces, but night as

it is in our time with automobiles on highways, and flashlights in

faces, and the eyes being deceived about shapes by the way the light

hits them. There is a streak of violence in me...I was interested in

the possibility of having a person dragged out of the area while lying

or sitting down. (Reprinted in Vaughan 1997, 135–7)

As Mark Franko has noted, the scene on the highway seems to be taken

right out of Cunningham’s personal experience while touring in

the infamous VW van with Rauschenberg, Cage, and his Company members

(1992, 146; also see Cunningham and Lesschaeve 2009, 106). Responding

to Cunningham’s directions, Rauschenberg invented a lighting

arrangement that would approximate an experience of the highway at

night he knew only too well, creating stark contrasts between total

obscurity and blinding illumination by cueing the lightboard to follow

an aleatory order of soft beams determined according to a chance

algorithm that changed for each performance. For the music, Cunningham

commissioned an original piece from La Monte Young, a composer who was

very much in vogue at the time. Young offered 2 Sounds, a

minimalist composition that has become over the years the object of a

lively polemic. 2 Sounds juxtaposes a screechy tone, produced

by dragging an ashtray against a mirror, with a more resonant low tone,

produced by stroking a piece of wood across the surface of a Chinese

gong. The first ten minutes of the dance are performed in absolute

silence. Cunningham heightened the contrast between the silent

beginning and the second half by amping up the volume of La Monte

Young’s score to a decibel level that most spectators (and

dancers) found—and still find—intolerable. Finally,

Rauschenberg added a piece of junk art to the scenography, a combine

composed of whatever he could find around the set at the time. (Don

McDonagh describes it as “a strange little machine with winking

lights... a cartoon version of an official police car.” [McDonagh

1976, 288–9]). Rauschenberg designed not only the sets and

lighting but also the costumes; he chose to dress the dancers entirely

in black with contrasting white sneakers on their feet. As for the

make-up, Rauschenberg elaborated on the sneaker motif: he applied a

black smudge under the eyes of each dancers, evoking in this way the

protective stroke of black that football players apply when they have

to play in a brightly-lit stadium. Significantly, during the rehearsals

for the Opéra Ballet production in Lyon, Jennifer Goggans directed

the dancers to scuff up and dirty the white sneakers as much as

possible presumably to give the impression—as in the original

production—of a grubby workspace, a stage graced only by the

clutter of unused equipment in the back.

Goggans’s explicit directive (to dirty the shoes) in the context

of the 2016 reconstruction confirms that none of the directions

Cunningham gave were indifferent or expendable. Clearly, he intended to

create a frame for the movement, he wanted to conjure a very specific

mood. Thus it was misleading to state—as he did—that any

association made by the spectators would be drawn “from

individual experience” alone. The lighting, the grubby

décor, the make-up, and the costumes all collude to render the

“falls” of Winterbranch not simply “facts in

dancing” but, more specifically, facts framed in a certain way.

That frame—the menace of nighttime darkness—remains a

constant throughout all performances of the piece. It is by no means

insignificant that Winterbranch, when excerpted later on for

an Event, was still performed in the original constumes and lighting;

as dance critic Nancy Dalva notes perspicaciously in her 2005 review,

of the Events at the Joyce Theater in New York, Winterbranch

was

presented in its own special outfits—namely black

jumpsuits—and its own almost completely dark, glancing, harsh

light. This was unusual for Events—I don’t know of any

other dance for which this is done—when the material is usually

stripped of its usual presentation context. (Dalva 2005, 18) [24]

The question is, to what extent does the dance material for Winterbranch rely on this “presentation context”?

Much of the choreography is period-specific; that is, we find in many

of the dances of the 1960s dance figures that evoke the workings of

machines—pulleys, pistons, and levers. A trio that occurs near

the end of Winterbranch is only a slight modification of a

trio found in Crises (1960); the turning figures in which one

dancer rolls over another prefigure similar figures found in Walkaround Time (1968). At the same time, the

“presentation context” of Winterbranch encourages

us to look at these figures and the gestures they contain not only as

mechanical but also as task-like, the variety of movement that would be

accomplished under the flickering, irregular lighting of an apocalyptic

landscape. At various points a dancer is dragged off the stage by means

of a small square black rug; we witness the effort involved in tugging

or carrying a body off stage and recognize the unmistakable silhouette

of a still figure wrapped in a shroud and transported on a stretcher.

The theme of the body as dead weight is thus impossible to miss,

although this theme seems to be contrasted with another, that of the

body as eloquent weight. It is as though Cunningham were

exploring the difference between what Agamben calls “bare

life” and “form-of-life,” that is, between

“naked life” and “a life that can never be separated

from its form” (or “shape”) (2000, 2–3). On the

one hand, the associations the audience makes with these

figures—victims of a holocaust, sinners writhing in

hell—are overdetermined by the context in which they are

presented; on the other, the gestures as performed arguably project

meanings that the scenography merely underscores.

Consider, for instance, the opening of the dance. A male

dancer—Cunningham, in the original

production—traverses the stage from back stage left to back stage

right lying on his back, wrapped tightly in a black tube that prevents

him from using his arms. (During the rehearsals for the 2016

reconstruction, Goggans referred to the tube as a “body

bag.”)[25] In the

original production, Cunningham held a flashlight so that while he

slithered and writhed, the beam would light up different areas of the

stage. The figure is thus at once a passive victim of the constraining

bag and an active participant in setting the mood of the piece.

Cunningham may have insisted that in choreographing Winterbranch he was merely interested in “the idea of

falling,” but the many props of the dance suggest that “the

idea of falling” was—even for him—by no means denuded

of symbolic implications.

The following sections of the dance also emphasize the weight of the

body, both as a thing to be manipulated and as a force to be countered

or taken into account. Soon after the opening solo, a man and woman

enter into a duet that resembles the awkward manoeuvres of a mechanical

pulley: one serves as a counterweight to the other. The man holds the

arm of the woman, who, to begin with, is lying on her side on the floor

facing the audience. Little by little he succeeds in lifting her torso,

head, and hips off the ground by leaning his feet against hers and

pulling her toward him with all his force. As soon as the woman is

upright, she begins to descend toward the other side, supported only by

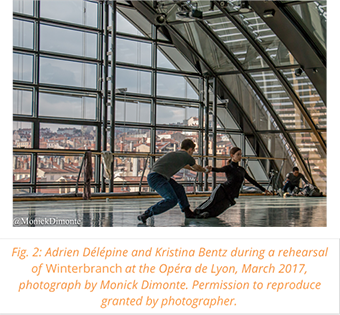

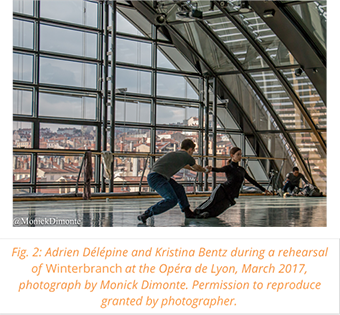

the counterweight of the man (see fig. 2). A few minutes later, the two

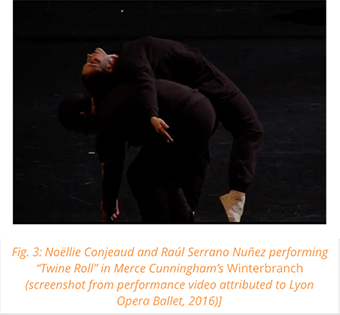

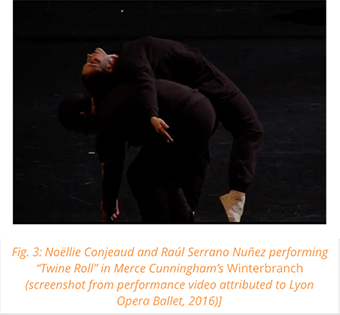

dancers form a figure that resembles a rotating ball inside a socket

(see fig. 3).

The following sections of the dance also emphasize the weight of the

body, both as a thing to be manipulated and as a force to be countered

or taken into account. Soon after the opening solo, a man and woman

enter into a duet that resembles the awkward manoeuvres of a mechanical

pulley: one serves as a counterweight to the other. The man holds the

arm of the woman, who, to begin with, is lying on her side on the floor

facing the audience. Little by little he succeeds in lifting her torso,

head, and hips off the ground by leaning his feet against hers and

pulling her toward him with all his force. As soon as the woman is

upright, she begins to descend toward the other side, supported only by

the counterweight of the man (see fig. 2). A few minutes later, the two

dancers form a figure that resembles a rotating ball inside a socket

(see fig. 3).

In both cases (the pulley and the ball-and-socket), the falls are

carefully controlled; we observe a calculated and steady displacement

of weight as the woman holds herself rigid, manipulated (but also

protected) by the motions of the man. In the second phrase, however,

which Cunningham referred to in his notes as the “twine

roll,” the woman makes herself completely vulnerable, rolling

over the back of the man, her back arched, exhibiting her pubis,

stomach, chest and throat to the audience. Meanwhile, the man

transforms himself into a support for her weight, bearing his burden

(the woman) as he shifts her toward the ground (see fig. 3).

In both cases (the pulley and the ball-and-socket), the falls are

carefully controlled; we observe a calculated and steady displacement

of weight as the woman holds herself rigid, manipulated (but also

protected) by the motions of the man. In the second phrase, however,

which Cunningham referred to in his notes as the “twine

roll,” the woman makes herself completely vulnerable, rolling

over the back of the man, her back arched, exhibiting her pubis,

stomach, chest and throat to the audience. Meanwhile, the man

transforms himself into a support for her weight, bearing his burden

(the woman) as he shifts her toward the ground (see fig. 3).

The duet seems to juxtapose contrasting tonalities: we witness industry

qualified by empathy, a task is executed with exquisite care. The

slowness of the first apparition of the “twine-roll” (it

will be repeated twice) invites the specator to contemplate the skill

of the dancers who are performing it. At one point during the

rehearsals I asked one of the women who performed the

“twine-roll,” Chaery Moon, what she thought the gestures

meant, what she was imagining as she executed the phrase. Her answer

was that she had no time to think about what her gestures might mean

because the balancing operation was so difficult to execute. The

challenge, she said, was to remain conscious of what her partner was

doing at every moment, to adjust her movements to the

micro-adjustments of his back muscles, to attend to the slow

but inexorable shifts of his weight beneath her prone

frame. In order to avoid falling and injuring herself, she had to

remain riveted on the incremental displacements of his weight,

displacements that were always in response to her own redistributions

of weight.

On the one hand, Moon’s account implies that the relationship

between the dancers was nothing more than a relation of weight. Of course, to some extent, this

relation characterizes all dance duets (especially ones in which there

are lifts), but this dancing “fact” is usually disguised by

mannerisms or narrative contexts. During the rehearsals for the

reconstruction, Goggans was careful to foreground this relation of

weight. Presumably channelling Cunningham, she explicitly instructed

the two dancers to avoid suggesting an amorous relation while

performing the “twine-roll.” At one point, the male and

female dancers (Mario Menendez and Chaery Moon) clasped hands as a way

of maintaining their balance. Goggans swooped down to correct them,

insisting that if they needed to hold hands to prevent themselves from

falling they could do so but only if their gesture remained invisible to the audience.

‘Do it in such a way that no one sees you’re touching each

other,’ she advised. To her mind, at least, any rapport between

dancers that might emerge over the course of the rehearsals had to be

muted; any plot that could be projected had to be suppressed.

The “twine-roll” appears twice more in the course of Winterbranch. The second time we encounter this phrase it is

executed by three couples simultaneously at a brisker pace. The third

and last time the “twine-roll” appears in the dance it is

performed at a much faster pace. As a result, the woman in each couple

is destabilized, caught off balance. Unable to calibrate her movements

to those of the man beneath her, she comes crashing down to the floor.

Each appearance of the “twine-roll” is thus distorted

either by slow motion or acceleration, indicating that Cunningham was

indeed interested in seeing how a “fact in dancing” could

appear each time in a different “shape.” Throughout the

1950s and 60s, deceleration and acceleration were among the means

Cunningham used to detach a potentially signifying gesture from a

particular context. Cunningham had other means at his disposal as well,

such as the breaking up or disaggregation of gestural continuities. We

can see how this disaggregating technique functions in another duet,

one that I will refer to, for lack of a better title, as “leaning

towards.” The “leaning towards” phrase is revelatory,

for it contains gestures that we recognize as meaningful (part of a

legible vocabulary of “intimate” human gestures) but that

suddenly become deprived of their context, shifting us into that

“abyss” toward which Cunningham directs his viewers. In

“leaning towards,” a man and a woman lean toward each other

until they balance precariously only a mere centimeter apart. Poised in

relevé, they execute a hinge in parallel, back to back. The male

dancer twists his upper body to the side, keeping his hips straight

ahead, then he extends his arms in the direction of the woman. Balanced

also in a hinge, she leans closer to him; he leans closer to her. But

they never touch. It is as though the man were reaching out to catch

the woman in her fall, a fall that never comes.

In the context of the phrase, his gesture could easily be read as a

gesture of protection. The moment is rich with longing and frustration,

proximity and distance, all the ingredients of a romantic duet. An

instant later, the woman abruptly stands up straight and the man

repeats the same protective gesture—as if to catch her—but

at a speed that the eye can barely register. This time, the gesture we

registered earlier as protective, takes on a mechanical quality; it is

detached from anything the other dancer is doing, emptied of affect and

integrated into what seems to be an arbitrary sequence of rapid,

interrupted, almost spasmodic gestures that bring the man to the floor.

We understand at this juncture that the gesture which seemed a moment

ago to be a gesture saturated with meaning, a “protective”

gesture, has been abstracted from its earlier function—as were

the accelerated gestures of the “twine roll.” Momentarily,

we glimpse something close—but not identical—to a

“fact in dancing,” an element in a taxonomy of such

“facts,” part of an alphabet or gamut of possible moves.

Isolated and abstracted, “to lean toward” seems to mean

little more than “to lean toward.”

But a question remains: Can a gesture be entirely liberated from a

context to reveal itself as “fact”? To answer that question

we need to consider the “shape” of the “fact”

and how that shape comes to appear. On one level, we might define the

shape that phenomenalizes the fact as the peculiar orientation the fall

takes when inserted into a continuity—here, when the hinge

appears first as part of a flowing protective gesture, then suddenly

abruptly as part of a chain of broken-up gestural bits. This

orientation can be considered the first order of shaping, the degree

zero of choreography as a time-based art. But this shape, inflected to

be sure by its place in a continuity, does not actually exist until it

has been executed by an individual dancer. That dancer also contributes

to “the further fact” that modifies—and in modifying

actualizes—the “fact in dancing.” The dancer,

that is, brings to the now oriented fact-shape not simply a momentum

and a rhythm but also an emotional color or mood. Finally, in addition

to the shape the “fact” takes within the continuity and the

singular dancer’s performance of it, there is the scenography,

the “presentation context” that ineluctably influences the

way the oriented, performed fact-shape will be perceived.

Given that for Winterbranch Cunningham opted for such a highly

charged presentation context, it is highly unlikely that he believed

the dance was just about “falling” or that ultimately he

wanted it to be interpreted as such. His careful directions to

Rauschenberg and his attempt to preserve the original scenographic

details of the work during Events indicate that an interpretative frame

for the movement mattered to him a good deal. The historical context of Winterbranch helps explain why this might have been so. The

period of the 1960s was one in which dance works addressed in

increasingly explicit ways contemporary political events. By 1964,

spectators would have been particularly alert to allusions in modern

dance to scenes of violence: The United States had just entered into

the war in Vietnam in 1961, and 1964 in particular was a year of

escalating violence, both in the air and on the ground. (The Gulf of

Tonkin attack was conducted on August 2, 1964.) If Cunningham wanted at

that very moment to display the simplicity of “facts in

dancing,” he made very little effort to guarantee that simplicity

in Winterbranch. Far from attempting to suppress associations

with recent and current events, he allowed them to multiply. The black

costumes, the rugs that serve as stretchers, the lighting evocative of

surveillance strobes—all these elements converge to amplify the

mood of menacing violence that the public couldn’t but apprehend.

Even at the level of the danced gestures themselves, which accelerate

over the course of the dance until they are performed at a frenetic,

break-neck speed, Cunningham seems to have been working with far more

than “the idea of bodies falling” (Vaughan 1997, 137).

In addition, there is much evidence to suggest that

“falling” carried many personal and literary associations

that Cunningham continued to explore throughout his career. His

“Choreographic Notes” are full of allusions to H. C.

Earwicker (Here Comes Everybody), the hero of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake who, let us recall, dies of a fall. There is no

reason to exclude the possibility that Cunningham associated the

“fact” of falling with literary figures, historical events,

religious symbols, and personal preoccupations, and that all of these

associations are present in the piece.. In any case, the cultural

associations of the act of falling are never far from the surface of Winterbranch. And how could it be otherwise? Falling is

without doubt the most symbolically weighted physical action that

exists.[26] It is by no

means clear, then, that the “fall,” as a gesture, could be

revealed, or even approached, as just a “fact.”

In addition, there is much evidence to suggest that

“falling” carried many personal and literary associations

that Cunningham continued to explore throughout his career. His

“Choreographic Notes” are full of allusions to H. C.

Earwicker (Here Comes Everybody), the hero of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake who, let us recall, dies of a fall. There is no

reason to exclude the possibility that Cunningham associated the

“fact” of falling with literary figures, historical events,

religious symbols, and personal preoccupations, and that all of these

associations are present in the piece.. In any case, the cultural

associations of the act of falling are never far from the surface of Winterbranch. And how could it be otherwise? Falling is

without doubt the most symbolically weighted physical action that

exists.[26] It is by no

means clear, then, that the “fall,” as a gesture, could be

revealed, or even approached, as just a “fact.”

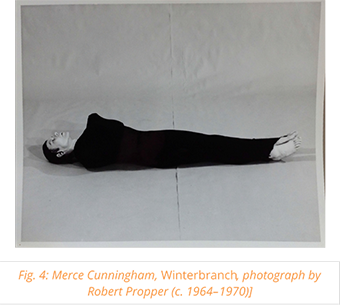

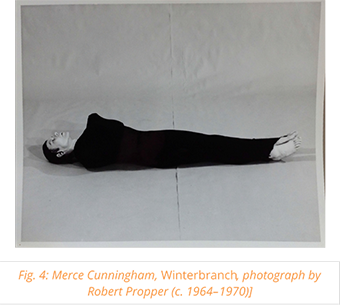

As if to bring the point home, Cunningham produced with the

photographer Robert Propper a series of studio stills of Winterbranch in the late 1960s that underscore the mortuary,

religious, and even pornographic implications of falling. Studio shots

are in general an untapped but important source of information about

Cunningham’s dances, for they indicate how he wanted the dance to

be publicized, emblematized, and recalled. Those taken by Propper are

particularly eloquent. In figure 4 we see Cunningham lying prone in his

black tube, a flashlight protruding strangely from the wrap, thus

suggesting a curious displacement—yet lingering presence—of

the erotic drive.

As if to bring the point home, Cunningham produced with the

photographer Robert Propper a series of studio stills of Winterbranch in the late 1960s that underscore the mortuary,

religious, and even pornographic implications of falling. Studio shots

are in general an untapped but important source of information about

Cunningham’s dances, for they indicate how he wanted the dance to

be publicized, emblematized, and recalled. Those taken by Propper are

particularly eloquent. In figure 4 we see Cunningham lying prone in his

black tube, a flashlight protruding strangely from the wrap, thus

suggesting a curious displacement—yet lingering presence—of

the erotic drive.

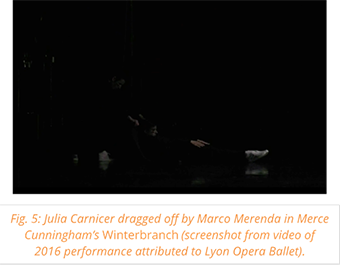

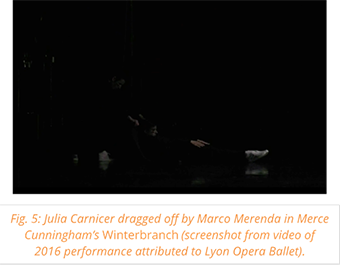

At no point in the dance does the male dancer lie in the position

Cunningham assumes for Propper’s photograph. However, near the

middle of the piece, a woman, lying still and prone on her back, is

indeed wrapped in one of the black carpets and dragged offstage by a

male partner (see fig. 5).

The studio still thus captures something central to the piece, not

“falling,” but rather the state of “having

fallen,” the weight of the stilled body as a material object

that, when presented on the stage, implies a narrative, a dramatic past

(“having fallen”). The question is, then, whether the

ethics of Cunningham’s dance should be located in what he

consistently represented as his refusal of symbolism, a resistance to

culturally over-determined meanings, or whether instead his ethics

inhere in both the movement and the presentation context, a

set of choreographic and staging decisions that at once confirm those

cultural meanings and put them to the test?

Part V. Conclusion: Winterbranch and the Ethics of Gesture

As in the example Agamben provides of the pornographic gesture suddenly

interrupted to expose its mediality, so too the gestures in Winterbranch expose their mediality, their quality as movement

support, while nonetheless retaining their connection to a frame, a

context, that suggests a way to interpret them. At times, Cunningham

seems to want to leave that frame behind, to remind us that the frame is a frame (not the “thing” itself), and even to

claim that it is ethical—or at least emancipatory—to do so.

And yet, I doubt Cunningham ultimately believed that it is either

ethical or emancipatory to seek to leave all frames behind, to suppress

all “particular forms” or “shapes,” to expose

the dancing “fact” as such. That would mean neglecting to

make a new continuity of the fragmented, disaggregated gestures with

which he worked (and he always emphasized with his dancers the need to

discover, in their own bodies, that new continuity); it would mean

suppressing the independence of the individual dancer who provides the

dynamic, the “shape,” the emotional color; it would mean

removing all scenographic choices and rejecting all studio stills in an

effort to keep the movement clean of context. If Cunningham sometimes

leaned in that direction, Winterbranch is clearly not an

example of that tendency.

Carolyn Brown hits the mark when she refers, in the passage quoted

earlier, to “the ethos of Winterbranch: darkness,

foreboding, terror, devastation, alienation, doom” (2007, 477).

Cunningham must have intuited that in 1964 it was time to produce a

more topical piece, to expose the fact that falling bodies are

eloquent, they are not just “facts” to be manipulated or

carted away. Winterbranch suggests that because we are human,

even simple shifts in weight can speak, can have something to

say—even if it is simply that the body is in danger of being

hurt. In that sense, Winterbranch is from beginning to end a

meditation on the body as a sensate, living organism subject to injury.

The pulley- and piston-like figures underscore the fragility of the

dancers as they lift and set one another down. The make-up Rauschenberg

devised for the dance points to the element of risk: the black smudges

under the eyes of the dancers at once protect them, literally, from the

blinding lights and suggest that vulnerability; the black smudges

recall to spectators the fact that the dancers, as sensate beings,

require protection. And this sense that dancers require protection

characterizes Cunningham’s approach to dance in general. He is

known to have adjusted his choreography—even if chance derived

and supposedly fixed—to prevent one dancer from colliding with

another, or to better control a lift. Choreography was always, for him,

a manifestation of care as well as an unfolding of the seemingly

impossible permutations suggested by chance. Thus it is not surprising

that elements of care are built into his technique. When I spoke to two

of the dancers cast to perform the phrase “leaning

towards,” Chiara Paperini and Tylor Galster, I learned that they

were both experiencing pain in their lower backs while performing the

hinge.[27] Trained

largely as classical ballet dancers, they were not used to executing

the kind of off-center hinges that are a primary building block of

Cunningham’s technique and choreographic vocabulary. During the

rehearsals Goggans, a seasoned Cunnngham teacher as well as dancer,

advised Paperini and Galster to make use of the muscles of the abdomen

to support the lower back in the hinge (as all Cunningham-trained

dancers learn in technique class). The care the dancers had to exercise

to protect their backs while performing the hinge must be considered a

significant part of the actualization of the dancing

“fact,” a component of its “shape” as

performed. It is precisely this aspect of the actualization that

constitutes what is gestural in the gesture: a sensitivity to the body

as a support, as a lived support. If Agamben and Cunningham

share an interest in the suspension of “communication” in

favor of “communicability,” if both view that suspension as

opening the ethical dimension, Cunningham adds a further element to

which he, as a choreographer and dancer, is acutely sensitive. That

element is the dancer’s own experience—as a medium, a

support for meaning, but also as a person living and shaping that

support-ness, that “media character,” on a stage.

The gesture in “leaning toward” that I interpreted as

protective demands focused concentration on the part of the dancer: she

must tighten the muscles of the abdomen, straighten the lower back, and

draw the sacrum in. To some extent, this skillful use of the muscles

becomes automatic over time; yet the effort involved always leaves a

trace in performance, what I have called elsewhere “the affect of

skill” (see Noland 2002, 120–35). This primary affect

already directs the gesture toward the pole of expression and meaning;

it gives the gesture its first shape, its first frame. Agamben shows

some sensitivity to this layer of lived experience when he writes in

“Le Geste et la danse” of “the dance of dancers who

dance on stage, the accomplishment of their skill as dancers and their power to dance as

power” (12; my emphasis). What Agamben refers to as the

dancers’s “skill as dancers” is not

“nakedness”; there is nothing pre-cultural or natural about

it (Cunningham in Vaughan 1997, 86). In fact, as an example of

technique it can be traced back to a very precise historical moment.

Dance technique, or skill, is a language; it is acquired, an

“accomplishment” that might, at times, afford an experience

of the “abyss.” It is the “linguistic” element

in gesture, a manifestation of our “linguistic nature,” or,

more precisely, of our natural disposition to be acculturated, to

acquire languages and skills, to become a vocal or gestural support for

signs. To stage this skill in its clearest form was always one of

Cunningham’s cherished goals—one could even say one of his

ethical goals. But skill is not the same thing as mediality “as

such,” or “expression as such,” or

“communicability” as “milieu pur.” Skill is

dirty and sweaty; it bears the marks not only of the person who attains

it but also of a specific training developed at a specific point in

time. As Winterbranch seems to insist, skill as exercised by a

dancer on stage is an invitation to a reading, an invitation to

interpretation, that, at certain historical junctures, it might be

unethical to ignore.

Winterbranch

can be said, then, to occupy one pole on a large spectrum of works in

Cunningham’s repertory, none of which—I maintain against

the grain—ever achieves, or could achieve, a display of energy in

its “naked” form. Winterbranch incessantly, even

doggedly, drags its gestures toward legibility, toward communication

and message, even as they are interrupted, suspended, exposed as the

instances of technique they also are. As in Agamben’s account,

the two orders—or extreme poles of the spectrum—co-exist:

the gesture is a sign (“communication”) and the gesture is

a support, a medium (“communicability”). The ethical

dimension is not opened, then, by seeking to suspend, to remain in an

“abyss” of endless mediality understood as a thing in

itself (“as such”). The ethical dimension is opened by

recalling that suspension is itself suspended, that we are

“condemned to meaning,” as Merleau-Ponty put it, and that

communication is a betrayal but also a chance. If at certain moments in

history it might be more ethical to press for the suspension of

semantics, even of expression, at others it might be more ethical to

emphasize the semantic and expressive weight a gesture can support.

There is ultimately no one way for art to be ethical, nor one way for

it to be political.[28]

It is impossible to ensure that a communication will be successful,

just as it is impossible to ensure that “nothing” will be

communicated at all. If the stage can display anything, it is that

fact.

Notes

[1] That Winterbranch was indeed a controversial work is

confirmed by the reviewers who saw it and the dancers who danced in