Introduction: Towards an Ethics of Gesture

Lucia Ruprecht, Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge

‘The gesture is the exhibition of a mediality: it is the process of

making a means visible as such. It allows the emergence of the being-in-a-medium of human beings and

thus it opens the ethical dimension for them’, Giorgio Agamben

writes in his Notes on Gesture (2000a, 58).[1]

This special section of Performance Philosophy takes

Agamben’s statement as a starting point to rethink the nexus

between gesture and ethics. While both are bound together here, their

association is not evident at first sight. What is an ethical gesture

if we assume that ethics concerns a good ‘way of being, […]

a wise course of action’, which is the Greek definition? Or, if

we go with the moderns, when we take it that ‘ethics is more or

less synonymous with morality’, with ‘how subjective action

and its representable intentions’ relate to a ‘universal

Law’, as in Immanuel Kant (Badiou 2001, 1–2)? What is such

a gesture if we understand by ethics, with Alain Badiou, a specific

relationship between subjective action and the extraordinariness of

what this philosopher calls ‘the event’—that

is, a ‘fidelity’ to particular, radical experiences of art,

science, politics, and love (67)? What might a Levinasian gestural

ethics look like, one that is grounded in the immediacy of an

‘opening to the Other’ which disarms the reflexive subject

(19)? Gesture has indeed been described as an opening of the body

beyond itself, as something that is often, or perhaps even necessarily,

relational. In her Inclinations: A Critique of Rectitude

(2016), Adriana Cavarero develops a decidedly gestural ethic which is,

as the title suggests, based on the posture of inclination: a bending

of the body towards those who are vulnerable and dependent, and whose

need of protection is as actual and given as that of a child. More

generally, it has been argued that the body in gestures is

‘attracted by the world, by an already existing object, by the

achievement of a future action that I can already perceive’, and

so is suspended vis-à-vis its opposite at a distance that allows a

specifically gestural ‘tension’ to ‘flourish’

(Blanga-Gubbay 2014, 125, 127). This implies that gesture often avoids

touch—although it may not exclude it—and thereby foregoes

the possessiveness of the haptic (Mowat 2016).

The ethical is tied to action and acting, to the ways in which one

conducts one’s life.[2]

Despite its diverse conceptualisations in the history of philosophy,

current understanding of the topic in cultural theory tends to rest on

a distinction between moral codes and ethics, which has found one of

its most acute formulations in the twentieth century in Michel

Foucault’s genealogical project.[3]

James Laidlaw describes it succinctly:

Foucault distinguishes between what he calls moral codes—rules

and regulations enforced by institutions such as schools, temples,

families and so on, and which individuals might variously obey or

resist—and ethics, which consists of the ways individuals might

take themselves as the object of reflective action, adopting voluntary

practices to shape and transform themselves in various ways […].

Ethics, including these techniques of the self and projects of

self-formation, are diagnostic of the moral domain. (2014, 29)

The gestural, by contrast, seems to come into its own where it departs

from what is usually considered manifest action, where it is taken out

of the functionality of an ‘operational chain’ (André

Leroi-Gourhan) to assume expressive or pantomimic power. Expressivity,

however, is only one element of gesturality, and functionality can be

handled creatively. As Asbjørn Grønstad, Henrik Gustafsson,

and Øyvind Vågnes outline in the introduction to their recent

collection Gestures of Seeing (2017), Vilém

Flusser’s influential theory of gestures distinguishes between

‘good and bad gestures’ in relation to how they interact

with a given apparatus, for instance the camera.[4]

Bad gestures, in this setting, follow the camera’s presumed

rules; good gestures imply ‘the active resistance of the

photographer to become a function of the apparatus she uses. The

gesture of photography, then, is an effort of resistance against the

apparatus (the program or code) by using it in ways not intended or

imagined by its inventors’ (2). Agamben’s expanded use of

the term apparatus thus seems to be in (unacknowledged) conversation

with Flusser. He writes: ‘I shall call an apparatus literally

anything that has in some way the capacity to capture, orient,

determine, intercept, model, control or secure the gestures, behaviors,

opinions or discourses of living beings’; and Flusser’s

effort of resistance returns in Agamben’s ‘hand-to-hand

combat with apparatuses’ to bring back to ‘common

use’ that which ‘remains captured and separated’ in

them (Agambem 2009, 14, 17). By differentiating ‘good’ from

‘bad’ modes of technical interaction, Flusser declares

photography to be an ethical (and indeed also philosophical) practice.[5]

He conceives of gesture as a ‘movement’ of good usage that

cannot be ‘objectively explained by [its] purpose or

function’: it ‘expresses the freedom to act and

resist’, in order to ‘truly communicate’

(Grønstad et al. 2017, 1). ‘To understand a gesture defined

in this way’, Flusser (2014) argues, ‘its

“meaning” must be discovered. […] The definition of

gesture suggested here assumes that we are dealing with a symbolic

movement’ (3).

The gestures of photography will recede, in the following, behind those

of film, dance, performance art, and philosophical discourse. But even

if photography is not one of the central media in this enquiry,

Flusser’s account of it advances our argument by thinking

together expression, communication, and action: we do things with gesture. That which has been introduced above

as gesture’s abstaining from (haptic) acting must, then, be

qualified. As the following contributions will amply demonstrate,

gesture—whether it is considered within or beyond the paradigm of

expression—does not evade the act; it possesses an agency that

might be called acting otherwise. It is in the forms, kinetic

qualities, temporal displacements, and calls for response which this

acting-otherwise entails that a gestural ethics takes shape. In other

words, gestures can act ethically as they en-act what they name, even

if their naming must always remain contested. Carrie Noland (2009)

argues that a gesture is a performative: ‘it generates an

acculturated body for others—and, at the same time, it is a

performance—it engages the moving body in a temporality that is

rememorative, present, and anticipatory all at once’ (17).[6]

As Rebecca Schneider will show, this temporality of gestural

performance is also reiterative and citational, bearing a capacity for

bringing back that which has been enacted before, but also enabling

reformulation and difference. Focusing on gesture’s

relationality, Schneider introduces a decidedly ethical slant to

political discussions of reiteration.

Despite the fact that the contributors to this special section do not

necessarily share the same definitions of gesture, a focus on the

ethical potential of gestural acts as singular instances of physical,

filmic and writerly performance unites their approaches. All of them

tease out the ethics of the works and acts that they address: dances by

Ted Shawn (Alexander Schwan) and Merce Cunningham (Carrie Noland),

films by François Campaux (Astrid Deuber-Mankowsky), John Ford,

George Stevens, and Clint Eastwood (Michael Minden), gestures of hail

and of political protest (Rebecca Schneider), and gestures of

philosophical criticism in Walter Benjamin (Mark Franko).

Indeed, all authors also trace, what Laura Cull (2012) in her Deleuzian

exploration of the immanent ethics of theatre calls, an ethical feeling

of ‘respectful attention’ or ‘attentive

respect’ in their various objects of enquiry (237).[7]

Gesture emerges more broadly as the gesturality of dance or as a

gestural mode of thinking and writing, and more narrowly, in specific

instances of expressive or functional movement, or of movement that

hovers at the cusp between the narrative and the non-narrative.

The following will both introduce the argument of each of the

contributors and continue to develop some of the overarching questions

posed by our collaborative investigation of the ethics of

gesture—what it might mean, what it might look like, and what it

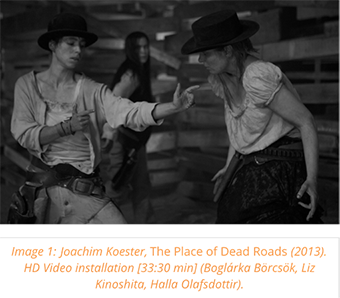

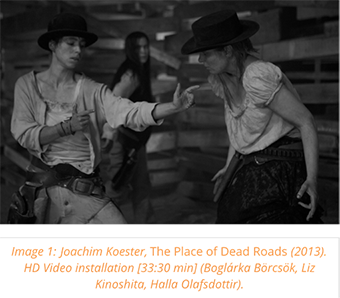

might do. Along the way, I will discuss two highly gestural video

installations by Danish artist Joachim Koester,The Place of Dead Roads (2013) and Maybe this act, this work, this thing (2016), which serve as

performed commentaries on the questions at hand.

Gesture, Potentiality, and Act in Agamben

To return to Flusser for a moment: His pictures are produced by a

photographer who communicates a subjective position in the shape of a

philosophical idea by leaving a kind of ‘fingerprint’ on a

surface (2011, 286). In Flusser, it is precisely the communication of

this intention which turns the activity of taking a photograph into a

gesture. He thus subscribes to a theory of expression that Agamben in

his understanding of gesture actively negates. Rethinking entirely

‘our traditional conception of expression’ (2002, 318),

Agamben’s gestures do not have any circumscribed intention. What

they communicate is ‘communicability’ (2000a, 59), the

dwelling in language of human beings. Agamben’s turn towards

mediality in his ‘Notes on Gesture’ has been much discussed

(see Grønstad and Gustafsson 2014), and will be productively

reread and probed with regard to filmic, dancerly and critical

performances in several of the following contributions. I will not

therefore go back to the essay’s argument in any detail here, but

will highlight one of its ethical concerns: that it is the emptying-out

or, with Simone Weil, ‘decreation’ (Saxton 2014, 62) of

meaning that frees gesture to become a carrier of potentiality; which

is, in Agamben, the condition for ethical choice. ‘The point of

departure for any discourse on ethics is that there is no essence, no

historical or spiritual vocation, no biological destiny that humans

must enact or realize’, he writes in The Coming Community (1993). ‘This is the only

reason why something like an ethics can exist, because it is clear that

if humans were or had to be this or that substance, this or that

destiny, no ethical experience would be possible—there would be

only tasks to be done’ (43).[8]

Where, then, is the place of the act in Agamben’s ethics of

potentiality? In the epilogue to The Use of Bodies (2016), the

ninth and final instalment of the Homo Sacer project, entitled

‘Toward a Theory of Destituent Potential’, Agamben explains

the relation between potential and act in Aristotle:

Potential and act are only two aspects of the process of the sovereign

autoconstitution of Being, in which the act presupposes itself as

potential and the latter is maintained in relation with the former

through its own suspension, its own being able not to pass into act.

And on the other hand, act is only a conservation and a

‘salvation’ (soteria)—in other words, an Aufhebung—of potential. (267)[9]

The operationality of Aristotle’s ‘potential/act

apparatus’ (276), however, must be interrupted to reach the

destituent potentiality towards which Agamben’s epilogue is

geared. What does Agamben mean by destituent potentiality? He uses the

term ‘destituent’ for grasping the paradoxical nature of

‘a force that, in its very constitution, deactivates the

governmental machine’ (2014, 65). This force does not simply

destroy a power or a function, but liberates ‘the potentials that

have remained inactive in it in order to allow a different use of

them’ (2016, 273). He conjures up a situation where potential

becomes a ‘constitutively destituent’

‘form-of-life’ (277):[10]

a ‘properly human life’ (277) from which, quoting Spinoza,

a ‘joy’ is born, where ‘human beings contemplate

themselves and their own potential for acting’ (278). Agamben

links destituent potentiality to a process of rendering inoperative or

neutralising operations in order to expose them, which is echoed in the

emptying-out of meaning that frees gesture to appear as such, and to

become a carrier of potentiality. Such destitution attempts to think an

act that does not act, or a non-act that acts: a (de)act(ivat)ing,

perhaps; or an acting-otherwise.[11]

The destituent is connected in Agamben to the advent of various kinds

of newness. With reference to Benjamin’s ‘Critique of

Violence’, the new emerges in the shape of the ‘proletarian

general strike’ (269): ‘“on the destitution [Entsetzung] of the juridical order together with all the

powers on which it depends as they depend on it, finally therefore on

the destitution of state violence, a new historical epoch is

founded”’ (268). With reference to Christ’s

deposition from the cross, the new emerges in the shape of redemption:

‘in the iconographic theme of the deposition […] Christ has

entirely deposed the glory and regality that, in some way, still belong

to him on the cross, and yet precisely and solely in this way, when he

is still beyond passion and action, the complete destitution of his

regality inaugurates the new age of the redeemed humanity’ (277).

With reference to the imagined politics that is intimated at the end of The Use of Bodies, destitution emerges, finally, in the shape

of a ‘constituted political system’ that embraces within

itself ‘the action of a destituent potential’, for which

[i]t would be necessary to think an element that, while remaining

heterogeneous to the system, had the capacity to render decisions

destitute, suspend them, and render them inoperative. […] While

the modern State pretends through the state of exception to include

within itself the anarchic and anomic element it cannot do without, it

is rather a question of displaying its radical heterogeneity in order

to let it act as a purely destituent potential. (279)

The vocabulary of contemplation, exposure, and display that informs the

preceding discussion leads us back, then, to the realm of the ethics of

(gestural) art, which (together with politics, in Agamben) names

‘the dimension in which works—linguistic and bodily,

material and immaterial, biological and social—are deactivated

and contemplated as such in order to liberate the inoperativity that

has remained imprisoned in them’ (278). Inoperativity is

associated with the energies of ‘anomie’ and of an

‘anarchic potential’ (273), that which is without law,

command or origin; that is—to draw on Agamben’s gestural

understanding—without pre-given meaning.[12]

Gestural acting-otherwise certainly includes strategies that, by making

given gestural routines inoperative, opens up a space for experiment,

improvisation, reflection, and the new. While anarchic and anomic

elements—from the resignification to the running wild of

gestures—do appear in the following case studies,

acting-otherwise is only partly characterised by such excessive forms

of inoperability. Often, subtler ways of modifying the operative

continuum will come to the fore, such as: the detaching of gestures of

violence from their usual ends, as in Koester’s The Place of Dead Roads; the delicate filmic

defamiliarisation, through slow motion, of the process of applying a

brush stroke, as Deuber-Mankowsky shows; or the rhythmical punctuation

of the continuum of thought with caesuras in Benjamin’s

‘physiological’ style, as traced by Franko. Noland’s

suggestion to consider gestural agency as ‘differential rather

than oppositional alone’ is path-breaking here, as it allows us

to study ‘a whole range of deviations from normative

behaviour—from slight variation to outright rejection—while

simultaneously construing the normative as equally

wide-ranging in its modes of acquisition’ (2009, 3).

Gestural Acting-Otherwise

Alexander Schwan’s essay ‘Ethos Formula: Liturgy and

Rhetorics in the Work of Ted Shawn’ (2017) opens this special

section by exploring forms of gestural normativity and ‘spiritual

vocation’ that fall to the wayside in Agamben’s gestural

ethics. Addressing how such gestural normativity is not only acquired,

but passed on through ethical attitudes ‘encoded’ in

movement patterns, Schwan turns to the other side of Agamben’s

self-reflexive modernism, exemplified by Ted Shawn’s liturgical

dances. With a head-nod in the direction of Aby Warburg’s pathos

formulae, Schwan suggests using the term ‘ethos formulae’

for postures and gestural routines which are ‘motivated by

decision-making rather than emotional content’’, while

still retaining a relationship with a form-giving or task-setting law.

Shawn’s choreographic aesthetics—or in fact,

ethics—is set within the greyzone between liturgy and modernist

dance and thus proves to be a rich ground for ethos formulae.

Influenced both by François Delsarte’s nineteenth-century

system of gestural meaning-making and his own Methodist background,

Shawn’s choreographic ‘decisions’ were guided by the

gestural ‘tasks’ which they carried out, and the

codifications which they performed. If gestures, as has been argued

above, can act ethically as they en-act what they name, Shawn made sure

that this ‘naming’ remained recognisable:

Standing upright and having his hands folded in front of his solar

plexus, he opened his arms slowly and symmetrically, raising them to a

point where his fingers still pointed to the ground and his open palms

reached towards the audience in a gesture of devotion, greeting and

blessing. (Schwan 2017, 32)

Moving from the gestural rhetoric of liturgy to that of the Western,

forms of generic recognisability are at stake in Michael Minden’s

essay too. His ‘Ethics, Gesture and the Western’ (2017)

begins with a brief discussion of Koester’s The Place of Dead Roads, which I would like to address in more

detail before turning to Minden’s argument. Koester’s

installation presents a group of four androgynous dancers in

nineteenth-century cowboy gear who are engaged in an apparently

involuntary, almost feverishly obsessive pantomimic reenactment of the

stock postures, gestures and moves of the Western genre: they eye and

circle each other chins down, launch into chimeric gun battles, revolve

as if lassoing, bounce as if riding a horse, convulse as if being hit

by a bullet or even ‘step-dance as if having their feet shot at

in the saloon’ (Börcsök 2017).

Sometimes, the recognisability of their moves is not so much a matter

of the latter’s mimetic shapes than of their ‘effort

quality’, to use Rudolf von Laban’s term: it is with

abruptness that the dancers swing around or stop and start movement

sequences, reminding us of the hypervigilance and the speedy reactions

of gunfighters. One description speaks of a deconstruction of the Wild

West’s ‘ritualised gestures’ (Camden Arts Centre

2017), pointing up the fact that the choreography (which was created by

Koester together with the striking performers Pieter Ampe,

Boglárka Börcsök, Liz Kinoshita and Halla Olafsdottir)

takes generic gestures out of their embedding in a plot structure. It

also takes them out of their usual gender assignment, as each dancer

enacts a vocabulary that would be considered largely masculine within

the genre-framework. At the same time, displacements of genre

vocabulary across body parts produce cross-over genderings: the

circling wrist movement of (a man’s) lassoing returns in the

undulations of a woman’s hips. For Noland, gesturality consists

not least in the fact that ‘movements of all kinds can be

abstracted from the projects to which they contingently belong’,

so that, ‘accordingly, they can be studied as both discrete units

of meaning and distinct instances of kinesis’ (2009, 6).

Koester’s video installation incites this kind of study. Detached

from their sites and props, from their usual operationality and from

narrative context, his gestures are performed in a space that is

similarly abstracted, segmented by loosely mounted wooden walls which

suggest make-shift cabins. The soundscape is denaturalised, amplifying

the inhales and exhales of breath, the shuffling of feet, and muffled

blows. A form of muffling also affects the field of the visual, with

the dancers moving in and out of shallow zones of focus, and even

moving in and out of camera frames, as if each medium shot defined a

new stage-like square.

Sometimes, the recognisability of their moves is not so much a matter

of the latter’s mimetic shapes than of their ‘effort

quality’, to use Rudolf von Laban’s term: it is with

abruptness that the dancers swing around or stop and start movement

sequences, reminding us of the hypervigilance and the speedy reactions

of gunfighters. One description speaks of a deconstruction of the Wild

West’s ‘ritualised gestures’ (Camden Arts Centre

2017), pointing up the fact that the choreography (which was created by

Koester together with the striking performers Pieter Ampe,

Boglárka Börcsök, Liz Kinoshita and Halla Olafsdottir)

takes generic gestures out of their embedding in a plot structure. It

also takes them out of their usual gender assignment, as each dancer

enacts a vocabulary that would be considered largely masculine within

the genre-framework. At the same time, displacements of genre

vocabulary across body parts produce cross-over genderings: the

circling wrist movement of (a man’s) lassoing returns in the

undulations of a woman’s hips. For Noland, gesturality consists

not least in the fact that ‘movements of all kinds can be

abstracted from the projects to which they contingently belong’,

so that, ‘accordingly, they can be studied as both discrete units

of meaning and distinct instances of kinesis’ (2009, 6).

Koester’s video installation incites this kind of study. Detached

from their sites and props, from their usual operationality and from

narrative context, his gestures are performed in a space that is

similarly abstracted, segmented by loosely mounted wooden walls which

suggest make-shift cabins. The soundscape is denaturalised, amplifying

the inhales and exhales of breath, the shuffling of feet, and muffled

blows. A form of muffling also affects the field of the visual, with

the dancers moving in and out of shallow zones of focus, and even

moving in and out of camera frames, as if each medium shot defined a

new stage-like square.

If the physical vocabulary of the Western is thus derealised and

exposed in its dance-like gesturality, the mechanically repetitive

performance of the dancers also exhibits the automatism with which

gestural regimes enter bodies, especially when automatic reaction is a

matter of survival in violent encounter. Koester refers to such

automatisms when speaking of a gestural move that he and the performers

called the ‘electric gun’, which they defined as an

‘electric current connected to holding a gun which would cause

the hand, the arm and sometimes the whole body to shake and

vibrate’ (Koester 2017b). Not only are bodies shown to be

radically immersed in and driven by their motor actions, we also get

the impression that many of their strategic moves are always already

infected by the tremors of combat trauma. This automatic gesturality

undergoes subtle changes in the course of the film, which is looped

indefinitely in the gallery space. Sequences where the dancers perform

the expected (if defamiliarised) score build up towards less

painstakingly executed, less obviously scripted and more anarchic

passages. Described by Koester as instances of a ‘happy

dance’ that ‘can be seen as an attempt to end the spell of

historic violence’ (2017a), these sequences constitute passages

of unleashed gestural force, moments of gestural recovery which at the

same time resemble gestural crises. Agamben’s fairly clear-cut

dialectic of gestures lost and regained (see Agamben 2000a) is

complicated here: While the bodies of the performers are bound up

within functioning representational patterns as long as they follow the

guiding rhetoric of the Western, they are performed by the

gestural vocabulary which they use; once they start performing

their own gestures, they cease to signify.

In an essay on contemporary Flemish dance, Rudi Laermans (2010)

describes such passages into non-signification with recourse to Agamben

as a foregrounding of ‘the body as a medium of non-verbal

expressivity that becomes notable as such only when the will to express

something is hampered by the very same body’ (411).[13]

This aesthetic of ‘gesturing dance’ variously discloses

‘the performing body as a failing medium of expressivity’,

one that paces out ‘the very limits of the body as a medium of

communication and representation, while still not giving up an

underlying sense of humanism’, or focuses on ‘the

borderline zone where physicality becomes expressive but does not yet

fully represent something. The very presence of the moving body then

crosses out its unavoidable “being in representation” when

performing in front of an audience’ (411–412). The Place of Dead Roads belongs on this terrain of gesturing

dance. Its choreographic oscillation between representationality and

non-representation thrives in the liminal spaces between the operative

and the inoperative, the scripted and the non-scripted. It derives its

ethics from the attentiveness and the reflectiveness with which it

crosses from one side to the other, or lingers on the various degrees

of entanglement between the two.

It is important to note that the muscular reactions, which have entered

the bodies’ neurophysiological set-up and form their motoricity,

are tied in Koester’s video installation to a history of

violence. By mimicking, rather than enacting, aggressive and defensive

moves—‘the performers never touch the revolvers they wear,

despite their obsessive miming of the gestures of aiming, shooting

etc’., writes Minden (2017, 40)—by in fact turning

functionally motivated movement into gestural movement, this history of

violence is placed at one remove, and finally interrupted when the

dancers slip into non-signification. What returns at this point is a

gestural acting-otherwise that abstains from launching into the

fully-fledged haptics of (violent) action. No longer-operational

movement is put to new use as gesture. The ethico-critical impact of

Koester’s work, then, participates in a genealogy that goes back

to Bertolt Brecht and Walter Benjamin. In her recent rereading of the

second version of Benjamin’s essay on Brecht’s epic

theatre, Judith Butler emphasises how gesturality, in this tradition,

can be defined as abstention from violent deed. Butler focuses on a

scene which Benjamin uses to explain how interruption becomes a

precondition for the production of gestus, and thereby for

discovering—in the sense of relearning to see, and possibly

change—the ‘conditions of life’ (Benjamin 1982, 152).

It is a scene from the stock elements of melodramatic middle-class

family drama in which the sudden entrance of a stranger prevents the

mother from hurling a bronze bust at her daughter, and the father from

calling a policeman from the open window. ‘Benjamin stops the

scene quite suddenly’, Butler (2015) writes,

giving us only the gesture, the frozen image, but not the act of

violence itself.

The gesture, then, functions as the partial decomposition of the

performative that arrests action before it can prove lethal. Perhaps this kind of stalling, cutting, and stopping establishes an

intervention into violence, an unexpected nonviolence through an

indefinite stall, one effected by interruption and citation alike. In

other words, the multiplication of gestures makes the violent act

citable, brings it into relief as the structure of what people

sometimes do, but does not quite do it—relinquishing the

satisfaction of the complete act for what may prove to be an ethos of restraint [my emphasis], if not a critical act of

nonviolence. (41)

Minden observes such an ethos of restraint in the John Wayne

character’s iconic lifting of his niece towards the end of John

Ford’s The Searchers, characterising it as a gestural

moment ‘in which a stronger person forbears from violence’

and ‘dominance’ (42). While literally stalling or foregoing

cruelty, moments like these also reflect back on gesturality as such,

drawing attention to its foregoing of the (possibly violent) act. But

Minden also addresses violence head-on. He joins Agamben in thinking

about gesture as a formal frame for communicability, and he relates

this to the similar function of genre. Even though few genres might be

more ‘generic’ than the Western, Minden argues, genre here

does not necessarily mean ‘destiny’ (Agamben 1993, 43).

Therefore, it does not have to be broken or ‘subverted’,

but should be considered a potentiality within which there are spaces

for ethical reflection. If genre thus provides the conditions for

communicability—for telling a story—its exposure of its own

narrative structures draws our attention to its intrinsic ethical

potential. As Minden shows, such an instance of exposure—or

‘exploitation’ (46)—of genre at the climax of Clint

Eastwood’s 1992 Unforgiven opens violence to

philosophical reflection by making ‘explicit’ and leaving

‘unresolved’ the Western’s ‘violent

payback’ formula (David Foster Wallace cited in Minden 2017, 48).

To come back to Agamben’s wording in The Use of Bodies,

the incommensurate or exceptional quality of the violent bloodbath that

takes place at the end of Unforgiven—its

‘anarchic’ and anomic nature—is removed from its

inclusion/exclusion within the establishment of justice, to be

displayed in ‘its radical heterogeneity’. Its ethical

appeal then consists in the fact that it acts indeed, despite its

manifest nature, ‘as a purely destituent potential’ (2016,

279). Fulfilling with hyperbolic excess and thereby at once remaining

within and deactivating generic demands, haptic violence itself becomes

gestural.

Astrid Deuber-Mankowsky’s essay ‘The Paradox of a Gesture,

Enlarged by the Distension of Time: Merleau-Ponty and Lacan on a

Slow-Motion Picture of Henri Matisse Painting’ (2017) leaves

Agamben behind, to address little-discussed gestural thinking in Lacan,

in juxtaposition to Merleau-Ponty and Benjamin. Deuber-Mankowsky

provides a close reading of Merleau-Ponty’s and Lacan’s

reactions to a slow-motion sequence of Matisse painting, shot in 1946

by François Campaux. Addressing how Merleau-Ponty and Lacan read

the minute hesitations of Matisse’s hand, Deuber-Mankowsky argues

for a gestural ethics that is rooted not so much in the

phenomenological body (as in Merleau-Ponty) or in the self’s

implication in its foundational relationship to a

‘gesturally’ organic unconscious (our relationship

‘to the organ’ [62], as in Lacan), but in the experimental

setting of the filmic medium: Benjamin’s technologically enhanced

‘room for play’ (Spielraum). This room for play is

characterised less by resistance against or combat with the apparatus,

as in Flusser and Agamben, but by the latter’s use as creative

and heuristic tool. Theodor W. Adorno, Deuber-Mankowsky reminds us,

took the technological dimension of this room for play seriously, and

saw its influence on literature too. He criticized Benjamin for linking

it, in his work on Kafka, to a Brechtian theatrical aesthetic rather

than a cinematic one. Adorno himself thought of Kafka’s gestures

as akin to the aesthetic of the silent movie (see Adorno 2001, 70),

situating them in the historical context of a modernist crisis of

representation that was perceived to be marked, not least, by a

‘dying away of language’. The specific animation or

life-force of Kafka’s gesturality, Deuber-Mankowsky argues, thus

appears to be infused with the technological energy of media of

reproduction, whose ‘rhythm […] reappears in gesture as a

trembling’ (63). Think, for instance, of the quivering élan

of ‘Desire to be a Red Indian’ (Wunsch, Indianer zu werden), or of the larger oscillations of

the two ‘gestural’ celluloid balls in ‘Blumfeld, an

Elderly Bachelor’ (Blumfeld, ein älterer Junggeselle), pointing up the dynamic (and

material) quality of the filmic medium.[14]

Gesture, here, becomes one of the fulcra of media change, and it is its

very embodiedness that allows it to do so. In the case of Kafka,

literary gesturality achieves a seismographic quality, one which is

reflective not only of the fact of a media revolution, but also of this

revolution’s not yet entirely firmed-up technicity; of a rhythm

that is not yet always, and in every instance, effortless. The

typically mechanical quality of the gestures that Kafka observes, that

he notes down in his diaries, and that serve as inspiration for the

bodily conduct of his protagonists often gives rise to the impression

that its functionality is in danger. In his Paris travel diary of 1911,

Kafka (1964) describes a man and two women in a hotel lobby: the

man’s ‘arm continually trembled as if at any moment he

intended to put it out and escort the ladies through the centre of the

crowd’. A few pages later we read about the less formal etiquette

of the brothel visit—where a gap-toothed ‘[girl]’ was

‘[a]nxious lest I should forget and take off my hat’ (456,

459). In his diary accounts of social gestures, Kafka notices moments

where codes of conduct draw special attention to themselves. They are

not naturally enacted—or avoided—but affected by a specific

kind of stress that bears on the potential of social automatisms to

fall out of kilter at any moment, making inoperative too, perhaps, the

conventionalised ‘busy-bodyness’ (Santner 2015, 102) which

they sustain. Butler considers this a kind of psychosocial dysfunction

with an implicit potential for transformation when she writes:

for the most part mechanical tends to be associated in popular language

with automatic, yet every mechanism has within itself the possibility

of not quite working as smoothly as it should. So though the mechanism

is governed by the reproduction of social relations through the

reproduction of the subject, there is sometimes “play” in

the mechanism, which means that it can veer in a different relation, or

it can, indeed, fall apart and fail to reproduce in the way for which

it is designed. Most of Kafka’s efforts to treat the mechanical

foreground this constitutive possibility of breakdown, or malfunction.

(Butler 2015, 23–24)

Technicity, in this context, is not just an indicator of shaky or

alienating rationality, or of hyper-intellectual

‘cybernetics’, as in Merleau-Ponty. The technical is also

defined by a ‘productivity’, as Deuber-Mankowsky writes,

which ‘revolutionizes not only perception, but the very relation

between the subject and knowledge’ (62).

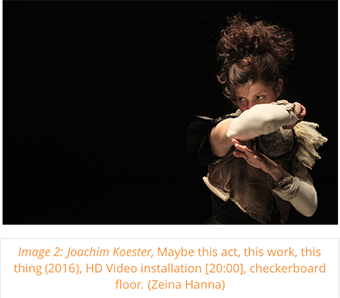

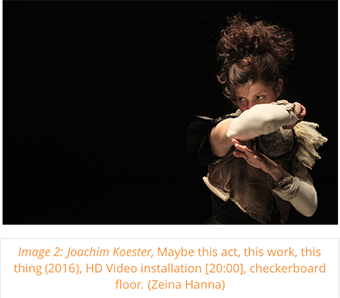

Koester’s video installation Maybe this act, this work, this thing, showcases this immense

promise of a filmic room for play, but also a sense of limitation or

malfunction in the shape of a certain gestural stress. Maybe this act is set in the very same turn-of-the-century

media revolution, as the writing of Benjamin and Kafka. It features two

dancers whose costumes indicate their association with the vaudeville

tradition in a stylised way, reenacting rather than reconstructing the

slightly worn glamour of pre-twentieth-century performance

practitioners. Koester’s film, the descriptive material argues,

conveys the advent of cinema through the bodies of vaudeville

performers. Mimicking the apparatus of a new world that threatens their

livelihood as stage actors, they simulate shutters of cameras and

projectors, quivering electricity and the whirring celluloid. Their

movements are amplified by the sounds of their heels hoofing, limbs

shuffling and voices muttering with a sense of desperate urgency that

echoes the cultural revolution that dawned with the film industry.

(Camden Arts Centre 2017)

Despite this situation of endangerment, the choreography also conveys

that the unfamiliar, different and expanded gesturality of the

apparatus enters the body in creative ways; it is productive of a new

kinaesthetic. Maybe this act is performed by Boglárka

Börcsök and Zeina Hanna, and choreographed by Liz Kinoshita

(both Börcsök and Kinoshita were also involved in The Place of Dead Roads). Börcsök’s webpage

includes an early draft by Koester that suggests a séance in which

the performers become spiritualistic ‘media’ for the new

medium of film: ‘They are channeling the spirit(s) of the newly

developed cinematic apparatus, miming the machine, embodying the

machine. As the spirit(s) enter they are transformed into cogs and

wheels and moving belts. […] Their movements are accompanied by

occasional moaning; like squeaks of metal and sizzling of hard

rubber’ (Börcsök 2017). Over the course of its

creation, however, the performance began to incorporate more agency:

the performers, Koester writes, are in fact ‘working on a new act

in a dimly-lit theater’ (STUK 2017), and do not seem to be in a

permanent state of possession, but of fine-tuned perceptiveness and

concentration. We are witnessing a rehearsal situation, where the

dancers are trying out poses—maybe this one, maybe

that—whispering to themselves, ‘marking’, that is,

suggesting gestural movement sequences instead of performing them to

completion. Rehearsing and working-towards become the (ethical) act in

this video installation. More casual, explorative passages are set off

against more frantic ones; routines are occasionally

metaphorical—such as a short tap dance section, or a brief

gesture of introduction, hands on lapels, mouth whispering ‘here

we are’—but more often metonymic—in other words,

suggesting a contiguity between body and filmic

apparatus—shoulders shuddering, fingers flickering, forearms

cutting squarely through the air. If Adorno (1996) writes

pessimistically in Minima Moralia of technology’s impact

on our ‘most secret innervations’, that it is making

gestures ‘precise and brutal’, expelling from movements all

‘hesitation, deliberation, civility’ (40), Koester opens up

a counter-vision, ‘an alternative space of possibility through

technologies, bodies and minds’ (STUK 2017), which is a space of

gestural room for play.

Despite this situation of endangerment, the choreography also conveys

that the unfamiliar, different and expanded gesturality of the

apparatus enters the body in creative ways; it is productive of a new

kinaesthetic. Maybe this act is performed by Boglárka

Börcsök and Zeina Hanna, and choreographed by Liz Kinoshita

(both Börcsök and Kinoshita were also involved in The Place of Dead Roads). Börcsök’s webpage

includes an early draft by Koester that suggests a séance in which

the performers become spiritualistic ‘media’ for the new

medium of film: ‘They are channeling the spirit(s) of the newly

developed cinematic apparatus, miming the machine, embodying the

machine. As the spirit(s) enter they are transformed into cogs and

wheels and moving belts. […] Their movements are accompanied by

occasional moaning; like squeaks of metal and sizzling of hard

rubber’ (Börcsök 2017). Over the course of its

creation, however, the performance began to incorporate more agency:

the performers, Koester writes, are in fact ‘working on a new act

in a dimly-lit theater’ (STUK 2017), and do not seem to be in a

permanent state of possession, but of fine-tuned perceptiveness and

concentration. We are witnessing a rehearsal situation, where the

dancers are trying out poses—maybe this one, maybe

that—whispering to themselves, ‘marking’, that is,

suggesting gestural movement sequences instead of performing them to

completion. Rehearsing and working-towards become the (ethical) act in

this video installation. More casual, explorative passages are set off

against more frantic ones; routines are occasionally

metaphorical—such as a short tap dance section, or a brief

gesture of introduction, hands on lapels, mouth whispering ‘here

we are’—but more often metonymic—in other words,

suggesting a contiguity between body and filmic

apparatus—shoulders shuddering, fingers flickering, forearms

cutting squarely through the air. If Adorno (1996) writes

pessimistically in Minima Moralia of technology’s impact

on our ‘most secret innervations’, that it is making

gestures ‘precise and brutal’, expelling from movements all

‘hesitation, deliberation, civility’ (40), Koester opens up

a counter-vision, ‘an alternative space of possibility through

technologies, bodies and minds’ (STUK 2017), which is a space of

gestural room for play.

The movement of the camera is highly perceivable here, sometimes giving

the impression of swinging back and forth in a slightly wonky way, as

if attached to the pendulum of a huge clock which both keeps time and

is dizzied by its change. Koester explains that he and the dancers

wanted the camera to be like a ‘third performer’ so that

‘sometimes the cinematographer would move as much as the

performers themselves’, filming ‘360 degrees’.

‘This eliminated the feeling of a privileged direction and

created the impression that the performers were not only “looking

for an act”, but also “for an audience”’

(Koester 2017b). Media competition becomes a form of not-quite-settled

media cooperation, reflecting back on the historical moment at the

beginning of the twentieth century, but also pointing up the capacity

and élan of screendance in the gallery space. Dance’s

modification by filmic intervention, that is, should not be considered

under the sign of loss (of liveness, presence, and immediacy), but as

the beneficial result ‘of a particular kind of longing for

kinesthetic stimulus that emerges from the space of optical

media’, as Douglas Rosenberg puts it (2012, 14–15). Optical

media allow us, not least, to observe gesture from great proximity, and

to do so repeatedly. They enable an enhanced kind of perception and a

specific kind of attentiveness, generating an echo in the viewer of the

dedicated focus of the performers on the new kinetic world of the

apparatus.

In light of the preceding remarks, an ethics of gestural

acting-otherwise can be further specified as appearing in a situation

that is suspended between the possibility of malfunction and the

potential of room for play. We might talk of a gestural ethics where

gesturality becomes an object for dedicated analytical exploration and

reflection on sites where this gesturality is not taken for granted,

but exhibited, on stage or on screen: in its mediality, in the ways it

quotes, signifies and departs from signification, but also in the ways

in which it follows a forward-looking agenda driven by adaptability and

inventiveness. Noland’s essay ‘Ethics, Staged’ (2017)

returns to these questions when asking: ‘What do dance gestures

expose that ordinary gestures do not? Why would such an exposure be

“ethical” in Agamben’s terms? And why would (his

notion of) the ethical rely on a stage?’ (67). One answer to

these questions is Agamben’s emphasis on the value of

contemplation, on the above-cited ‘joy’ of ‘human

beings’ who ‘contemplate themselves and their own potential

for acting’ (2016, 278). This emphasis on self-reflection and

potentiality might be challenged, of course. Cavarero—without

engaging with Agamben—does so by developing her ethics of the

inclined posture from the immediate givenness of a ‘sure and

practical love, so everyday and spontaneous that it does not express

signs of suffering or self-sacrifice, and even less of excessive

self-awareness’ (2016, 174). Noland’s essay, in turn,

scrutinises Agamben, bringing to the fore how the

‘gesturality’ of gesture is exposed, on stage, and in

dance; and furthermore, how such exposure, while carrying ethical

potential, cannot ever be exclusively ‘pure’.[15]

This reading is especially provocative as it focuses on the major

proponent of twentieth-century ‘pure dance’, choreographer

and dancer Merce Cunningham, through the 2016 reconstruction of his

1964 choreography, Winterbranch. Noland critically engages

both with the tenets of Cunningham scholarship and with Agamben’s

mediality of gesture by writing ‘[a] means is never pure

[…] it can in fact never be exposed as “an end in

itself”’ […] the means is itself mediated by what it bears’ (72). Rereading

Agamben’s analysis of pornography, Noland questions the idea that

Agamben ‘opens the ethical dimension […] at the point where

communication is lost’. Instead, she argues that he does so

at the point where saying ‘something in common’ (the

clearly legible pornographic gesture) and saying ‘nothing’

(the gesture interrupted, exposed as a gesture) occur simultaneously.

[…] He points us toward that ambiguous point where a narrative

unfolds and yet that narrative is suspended, revealing a

‘stratum’ ‘not exhausted’ by a narrative

[…], a point where the communication is interrupted, yet still

‘endured’. (72)

Noland locates the ethics of Winterbranch precisely at this

point—the choreography ‘practices an ethics of gesture

insofar as it suspends movement between an “impure”

manifestation (“passion for her”, “anger against

him” [Cunningham quoted in Noland 2017, 73]) and raw human

kinesis imagined as a “pure” support’.

Noland’s essay also demonstrates that strategies for the exposure

of gesturality go beyond Brecht’s and Benjamin’s emphasis

on interruption, still very present in Butler’s engagement with a

stalling ‘ethos of restraint’ (2015, 41). Noland singles

out, for instance, the modifications of one of Winterbranch’s partnering movements, where a female

performer rolls in a deep arch across the bent back of a male

performer, while the front of her body is exposed. Depending on the

style and speed of its execution, this movement, which is based on the

relation of weight between two people, exposes its gestural potential

by creating impressions ranging from protectiveness to possible crash.

When executed carefully, however, it draws out nuances of

‘kinaesthetic awareness’ (Brandstetter 2013)—of how

it might feel to perform a movement—which might be re-imagined in

an equally kinaesthetic sense by an audience who tunes into the dancing

on stage (also see Reynolds 2007 and Foster 2010).

Mark Franko’s essay, ‘The Conduct of Contemplation and the

Gestural Ethics of Interpretation in Walter Benjamin’s

“Epistemo-Critical Prologue”’ (2017), observes an

equally kinaesthetic (and ethical) sensibility in Benjamin’s

style of thinking and writing. Franko is concerned with the gestural

quality of literary and philosophical interpretation, with the

‘rhythm’ and ‘relative velocity’ that structure

‘the operations of critical attention’ (91) which Benjamin

describes in his prologue (Vorrede) to

The Origin of German Tragic Drama (Ursprung des deutschen

Trauerspiels)

. Benjamin is addressing his own method here, and Franko shows how this

method is defined by a discontinuous temporality. Meticulous in its

detours, it is marked by the intermittency of breathing, and by the

stops and starts of turning towards and stepping back from the object

of study.[16]

Gesturality, in this case, is less a matter of content than of mode, of

the temporal and spatial choreography of what Franko calls the conduct

of contemplation.[17]

Franko argues that the ethics of such conduct lies in the

‘essential rapport’ and ‘performative relation

[…] with the interpretive content of the analysis and, hence, to

the artwork or works under scrutiny’ (91)—in our example,

German baroque drama. The sequentiality of contemplation that

‘always encounters its own death in and as expired breath’

thus adapts to the broken historicity of baroque drama as mourning

play, which is fragmented by ‘mortality and decay’ (95,

99). Franko’s ‘essential rapport’ might, in

Badiou’s words, be called a gesture of ethical

‘fidelity’ to the Trauerspiel, brought about by

Benjamin’s radical experience and ‘sustained

investigation’ of the genre (Badiou 2001, 67).

Franko’s elaboration of Benjamin’s gestural method, then,

also goes beyond Agamben’s pure mediality of gesture. And again,

a questioning of violence comes into play. Here, with Franko’s

elucidation of Agamben’s use of Benjamin’s idea of

‘violence as pure medium’, which leads Agamben to

‘the idea of gesture in his later essay as itself the

communication of communicability, or a means without end’ (93).

Arguing for a more complex understanding of gesture and the ethics of

gesture in Benjamin, Franko considers gesturality as instrumental to

the methodology of philosophical criticism. This is less a matter of a

presumed fullness or emptiness of gesture, than it is of the fact that

‘any gestural “manifestation” becomes caught up in

reflection’, as Franko suggests (102–103). This burden of

reflection affects the temporality of processes of reading and

understanding. He specifies: ‘While the communication of

communicability would presumably be instantaneous and

swift’—as swift as ‘the sovereign decision’, or

a physical act of violence—‘the ethical gesturality that

emerges as method in the Vorrede is founded on a rejection of

the “purity” of gesture because said purity must by

definition remain inaccessible to a hermeneutics’ (103).

Benjamin’s enhanced gestural awareness links a style of writing

and thinking to the bodily performances of gesture which are discussed

in the other contributions to this special section. Rather than the

differences between writerly, dancerly, and filmic gestures (see Ness

2008 and Noland 2008), our focus on ethics seems to draw out their

fault lines. A gestural ethics is also a prime site for the fault lines

between theatre, dance (or film) studies, and performance studies.

Gestural practice or action is a performance that does not require the

proscenium stage (or screen); as Noland (2009) argues: ‘the term

“gesture” […] encourages us to view all movements

executed by the human body as situated along a continuum—from the

ordinary iteration of a habit to the most spectacular and

self-conscious performance of a choreography’ (6).

Schneider’s approach exemplifies this sense of the expanded

gestural stage. Her contribution, ‘In our Hands: An Ethics of

Gestural Response-ability’ (2017), not only revisits her own

thinking and writing about gesture across her work to date, but also

indicates the directions that it might take in the future, and the kind

of ethics this might yield.

As the final piece of this special section, Schneider’s essay

opens up the field in more than one way. Taking the form of a

conversation that was triggered by a number of questions that I posed

to begin with, it might be called a ‘response’, but it also

develops an ethics of ‘response-ability’ that goes beyond

the singular writing situation, to reflect on relationality as a

fundamental ethical category of calling out, and answering calls.

Rethinking her explorations inThe Explicit Body in Performance and Performing Remains of gestural reiteration and citation, and

their potential to at once reinstate the same and bring about the

different, Schneider engages with the gesture of the hail. Both

predicated upon a fundamentally ethical relationality (see Benjamin

2015, Levinas 1969) and susceptible to ideological investment, the hail

epitomises the operations of the ‘both/and’, a logic of

conjunction that structures and punctuates Schneider’s thoughts

on gesture: from the classic Brechtian tactic in which performance both

replays and counters conditions of subjugation to Alexander

Weheliye’s reclamation of this tactic for black and critical

ethnic studies. The gesture of the hail leads us, then, to the gesture

of protest of the Black Lives Matter movement. The hands that are held

up in the air both replay (and respond to) the standard pose of

surrender in the face of police authority and call for a future that

might be different. By doing so, this gesture of protest literally

stages what has been called, at the beginning of this introduction, a

Levinasian ‘opening to the Other’, albeit in a situation of

threat and resistance to threat: a gesture of disarmament which also

disarms the onlooker.

Without going back to Agamben, Schneider’s response also

radically questions the viability of a pure mediality of gesture, as

such a proposition would need to be predicated upon the assumption that

everyone has equal opportunity to blend in with the unmarked agent of

this mediality, the ahistorical ‘liberal humanist figure’

(Weheliye 2014, 8) of white Man. What her response-ability thus equally

effectuates, is a shift away from potentiality as unmarked space.

Following Schneider’s argument, gesture’s acting-otherwise

can only ever be accomplished by the ways in which gestures act on

their own implication in the signifying structures of gender,

sexuality, race, and class, on how these structures play out

relationally across time and space, and between historically and

locally situated human beings.

To conclude: A note of thanks. A series of serendipitous moments made

this project possible. It began in summer 2015, when I was encouraged

to apply for conference support by a newly-established network—an

application that was, in the end, unsuccessful. But instead, the

Schröder Fund and the German Endowment Fund of the Department of

German and Dutch at the University of Cambridge stepped in, and my

thanks goes to the boards of these two funds, especially to Sarah

Colvin. In his editorial note to that summer’s issue of Dance Research Journal, Mark Franko (2015) suggested that the

assembled contributions, which included an article of mine, together

worked ‘toward an ethics of gesture’ (1)—a

formulation which I found so pertinent that it stuck in my mind, so

much so that I turned it into the title of the symposium that I

organised at Emmanuel College, Cambridge in April 2016. Thanks are due

to Alyce Mahon and Andrew Webber, who chaired sessions during the day

and enriched the discussion with their interventions. I also thank

Emmanuel College for the provision of conference facilities and for a

memorable dinner. All but one of the contributions to the symposium are

documented in this special section. Jonas Tinius, for whose input I

remain grateful, decided to publish his contribution elsewhere; Rebecca

Schneider agreed to embark on a question-based revisiting of her work

on gesture instead of contributing her conference paper, leading to a

shared intellectual journey that proved as exciting as it was

enlightening—my heartfelt thanks are due to her. A brilliant

gesture workshop at the Warburg Institute London, which took place in

December 2016, confirmed my sense that a renewed engagement with

gesture in and beyond Agamben was warranted, and I thank Andrew

Benjamin and Christopher Johnson for their hospitality and for

facilitating such stimulating discussions during that event. I had the

good fortune of being able to attend a seminar by Mark Franko at

Gabriele Brandstetter’s series of research colloquia at Free

University Berlin in January 2017, where he developed the elegant

gestural reading of Benjamin’s epistemo-critical prologue which

is testified to in his present contribution to this special section. I

would also like to extend my thanks to Joachim Koester, whose art

instigated much of the thinking in this introduction, and who so

generously shared his works and insights.

I am thrilled that Performance Philosophy agreed to publish

the following array of articles, and my thanks goes to the editors,

especially to Theron Schmidt, for their support throughout the

publication process; to the anonymous reviewers, for their careful

reading and expert advice; to Rosa van Hensbergen, for her brilliant

editorial and administrative assistance and wonderful dance

conversation; and, last but not least, to all of the contributors, for

their stellar work, and for the enthusiasm with which they entered into

this collaborative exploration of how gesture acts otherwise.

Notes

[1] Giorgio Agamben first published this text in 1991 under the title

‘Notes sur le geste’ in the cinema journal Revue Trafic, founded in the same year by French film

critic Serge Daney.

[2] Note here the topic of this year’s Performance Philosophy conference (Prague 2017),

‘How does Performance Philosophy Act? Ethos, Ethics,

Ethnography’.

[3] For current research in the anthropology of theatre and performance

that engages with the ethics of theatre and rehearsal practice as a

form of Foucauldian self-cultivation, see, for example, Tinius

(2015).

[4] Flusser’s theory was published in German in 1991, the same

year as ‘Notes sur le geste’. In 2014, an English

translation appeared under the title Gestures.

[5] ‘The gesture of photographing is a philosophical gesture, or

to put it differently: since photography was invented, it is

possible to philosophize not only in the medium of words, but also

in that of photographs. The reason is that the gesture of

photographing is a gesture of seeing, and so engages in what the

antique thinkers called “theoria,” producing a picture

that these thinkers called “idea”’ (Flusser 2011,

286).

[6] Even though Carrie Noland’s seminal Agency and Embodiment (2009) does not explicitly focus on

the ethics of gesture, its engagement with the agency of

kinaesthetic experience, and with the subtleties and varieties of

gestural deviations as well as norms, provides cornerstones for the

present enquiry.

[7] See also André Lepecki’s notes on Gilles Deleuze and an

ethics of dance, as ‘a project of affirming life as a desire

to activate powers (pouissance) and affects that are not

bound to organizational tyrannies or majoritarian imperatives on

how to live one’s life’ (2007, 119).

[8] For a discussion of this passage, see also Minden and Schwan in

this special section.

[9] Aufhebung is used here in the Hegelian sense of both

‘abolishment’ and ‘preservation’.

[10] For Agamben’s use of ‘form-of-life’, see the

following: ‘By the term form-of-life, […] I

mean a life that can never be separated from its form, a life in

which it is never possible to isolate something such as naked life.

[…] It defines a life—human life—in which the

single ways, acts, and processes of living are never simply facts

but always and above all possibilities of life, always and above

all power (Agamben 2000b, 3–4).

[11] In contrast to Agamben’s ‘action of a destituent

potential’, my use of ‘acting-otherwise’ shifts

the emphasis from philosophical reflection to corporeal practice,

while retaining Agamben’s differentiation between action that

constitutes something and action that is potential and destituent.

I suggest ‘acting-otherwise’ as a general formula that

needs to be fleshed out and made specific by addressing the

particularities of singular gestural practice, which take

precedence over and might challenge philosophical consistency. It

would be fruitful, but goes beyond the scope of this introduction,

to include a third term here, Deleuze and Guattari’s ‘ agencement’, as used recently by Erin Manning

(2016). As opposed to agency’s focus on an individual or a

group’s volition, agencement values ‘modes of

experience backgrounded in the account of agency’, especially

those that deviate from neurotypicality; agencement also

‘carries within itself a sense of movement and

connectibility’ (123), questioning any clear-cut dialectic of

willed/unwilled action.

[12] Agamben’s use of ‘gag’ in Notes on Gesture as ‘something that could be put in

your mouth to hinder speech’, but also ‘in the sense

‘of the actor’s improvisation meant to compensate a

loss of memory or an inability to speak’ (2000a, 59) is

another way of naming that which he, in The Use of Bodies,

calls the ‘constitutively destituent’ (2016, 277).

[13] It should be noted here that the dancers who perform in The Place of Dead Roads are all linked to the Flemish

dance scene which Laermans addresses.

[14] Andrew Webber writes: ‘The balls are, suitably enough, made

of celluloid: fabricated, that is, as objects of projections for a

theatrical home-movie’ (Webber 1996, 327).

[15] For a helpful philosophical discussion of ‘purity’, see

Cull (2012, 229–234).

[16] Compare Koester’s amplification of the sounds of

breath-taking in The Place of Dead Roads, and

Minden’s remarks on gestures of breath in his contribution to

the special section.

[17] Franko’s gestural ethics of interpretation should therefore

not be confused with Agamben’s ‘gestic

criticism’, which is concerned with the

‘intention’ of the work or works that are being studied

(1999, 77).

Works Cited

Adorno, Theodor W. 1996. Minima Moralia. Translated by E. F.

N. Jephcott. New York: Verso.

———. 2001. ‘Letter of 17. 12. 1934’. In

Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, The Complete Correspondence 1928–1940, edited by Henri

Lonitz, translated by Nicholas Walker, 66–72. Harvard: Harvard

University Press.

Agamben, Giorgio. 1991. ‘Notes sur le geste’. Translated by

Daniel Loayza. Revue Trafic 1, 31–36.

———. 1993. ‘Ethics’. In The Coming Community, translated by Michael Hardt, 43–44.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

———. 1999. ‘Kommerell, or On Gesture’ in Potentialities: Collected Essays in Philosophy, edited and

translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen, 77–85. Stanford: Stanford

University Press.

———. 2000a. ‘Notes on Gesture’. In Means Without End: Notes on Politics, translated by Vincenzo

Binetti and Cesare Casarino, 49–60. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.

———. 2000b. ‘Form-of-Life’. In Means Without End: Notes on Politics, translated by Vincenzo

Binetti and Cesare Casarino, 3–12. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.

———. 2002. ‘Difference and Repetition: On Guy

Debord’s Films’. In Guy Debord and the Situationist International: Texts and Documents, edited by Thomas McDonough, translated by Brian Holmes, 313–319.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

———. 2009. ‘What is an Apparatus?’ In What is an Apparatus and Other Essays, translated by David Kishik

and Stefan Pedatella, 1–24. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

———. 2014. ‘What is a Destituent Power?’

Translated by Stephanie Wakefield. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1068/d3201tra

———. 2016. The Use of Bodies. Translated by Adam

Kotsko. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Badiou, Alain. 2001. Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil. Translated by Peter Hallward. London: Verso.

Benjamin, Andrew. 2015.

Towards a Relational Ontology: Philosophy’s Other Possibility.

New York: Suny.

Benjamin, Walter. 1982. ‘What is Epic Theatre?’. In Illuminations, translated by Harry Zohn,149–156. New York:

Harcourt.

Blanga-Gubbay, Daniel. 2014. ‘Life on the Threshold of the

Body’. Paragrana 23 (1):122–131.

https://doi.org/10.1515/para-2014-0012

Börcsök, Boglárka. 2017a. ‘Maybe This Act, This Work,

This Thing by Joachim Koester (2016)’. Boglárka Börcsök. Accessed October 5.

https://boglarkaborcsok.wordpress.com/dancer-performer-collaborator/the-place-of-dead-roads/

———. 2017b. ‘The Place of Dead Roads by Joachim

Koester (2013)’. Boglárka Börcsök. Accessed

October 5.

https://boglarkaborcsok.wordpress.com/dancer-performer-collaborator/the-place-of-dead-roads/

Brandstetter, Gabriele. 2013. ‘Listening: Kinesthetic Awareness in

Contemporary Dance’. In

Touching and Being Touched: Kinesthesia and Empathy in Dance and

Movemen

, edited by Gabriele Brandstetter, Gerko Egert, and Sabine Zubarik,

163–179. Berlin: De Gruyter.

https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110292046.163

Butler, Judith. 2015. ‘Theatrical Machines’. Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 26 (3):

24–42.

https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-3340336

Camden Arts Centre. 2017. ‘What’s on: Joachim Koester. In the

Face of Overwhelming Forces’. Camden Arts Centre. Accessed

October 5.

https://www.camdenartscentre.org/whats-on/view/koester

Cavarero, Adriana. 2016. Inclinations: A Critique of Rectitude.

Translated by Amanda Minervini and Adam Sitze. Stanford: Stanford

University Press.

Cull Ó Maoilearca, Laura. 2012. Theatres of Immanence: Deleuze and the Ethics of Performance.

Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Deuber-Mankowsky, Astrid. 2017. ‘The Paradox of a Gesture, Enlarged

by the Distension of Time: Merleau-Ponty and Lacan on a Slow-Motion Picture

of Henri Matisse Painting’. Performance Philosophy 3 (1):

53–65.

https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2017.31164

Flusser, Vilém. 2011. ‘The Gesture of Photographing’. Journal of Visual Culture 10 (3): 279–293.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412911419742

———. 2014. Gestures. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816691272.001.0001

Foster, Susan Leigh. 2010. Choreographing Empathy: Kinesthesia in Performance. New York:

Routledge.

Franko, Mark. 2015. ‘Editor’s Note: Toward an Ethics of

Gesture’. Dance Research Journal 47 (2): 1–2.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0149767715000248

———. 2017. ‘The Conduct of Contemplation and the

Gestural Ethics of Interpretation in Walter Benjamin’s

“Epistemo-Critical Prologue”’. Performance Philosophy 3 (1): 91–106. https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2017.31166

Grønstad, Asbjørn, and Henrik Gustafsson, eds. 2014. Cinema and Agamben: Ethics, Biopolitics and the Moving Image. New

York: Bloomsbury.

Grønstad, Asbjørn, Gustafsson, Henrik, and Øyvind

Vågnes, eds. 2017. Gestures of Seeing in Film, Video and Drawing. New York:

Routledge.

Kafka, Franz. 1964. Diaries 1910–1923. Edited by

Max Brod, translated by Joseph Kresh, Martin Greenberg and Hannah Arendt.

New York: Schocken.

Koester, Joachim. 2017a. ‘The Place of Dead Roads’.

Wall-mounted description at Camden Arts Centre, London, where the video

installation was exhibited from 28 January to 26 March 2017.

———. 2017b. Email conversation with Lucia Ruprecht. April

29.

Laermans, Rudi. 2010. ‘Impure Gestures Towards ‘Choreography in

General’: Re/Presenting Flemish Contemporary Dance,

1982–2010’. Contemporary Theatre Review 20 (4):

405–415.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10486801.2010.50576

Laidlaw, James. 2014. ‘The Undefined Work of Freedom:

Foucault’s Genealogy and the Anthropology of Ethics’. In Foucault Now: Current Perspectives in Foucault Studies, edited by

James Faubion, 23–37. Cambridge: Polity.

Lepecki, André. 2007. ‘Machines, Faces, Neurons: Towards an

Ethics of Dance’. TDR 51 (3): 118–123.

https://doi.org/10.1162/dram.2007.51.3.118

Levinas, Emmanuel. 1969. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Translated by

Alphonso Lingis. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press.

Manning, Erin. 2016. The Minor Gesture. Durham: Duke University

Press.

Minden, Michael. 2017. ‘Ethics, Gesture and the Western’. Performance Philosophy 3 (1): 39–52.

https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2017.31160

Mowat, H. B. 2016. Gesture and the cinéaste: Akerman/Agamben, Varda/Warburg

(doctoral thesis).

https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.6333

Ness, Sally Ann. 2008. ‘Conclusion’. In Migrations of Gesture, edited by Sally Ann Ness and Carrie Noland,

259–279. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Noland, Carrie. 2008. ‘Introduction’. In Migrations of Gesture, edited by Sally Ann Ness and Carrie Noland,

ix–xxviii. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

———. 2009. Agency and Embodiment: Performing Gestures/Producing Culture.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674054387

———. 2017. ‘Ethics, Staged’. Performance Philosophy 3 (1): 66–90.

https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2017.31165

Reynolds, Dee. 2007.

Rhythmic Subjects: Uses of Energy in the Dances of Mary Wigman, Martha

Graham, and Merce Cunningham

. Hampshire: Dance Books.

Rosenberg, Douglas. 2012. Screendance: Inscribing the Ephemeral Image. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Santner, Eric. 2015.

The Weight of All Flesh: On the Subject-Matter of Political Economy, edited by Kevis Goodman. New York: Oxford University Press.

Saxton, Libby. 2014. ‘Passion, Agamben and the Gestures of

Work’. In Cinema and Agamben: Ethics, Biopolitics and the Moving Image, edited by Asbjørn

Grønstad and Henrik Gustafsson, 55–70. New York: Bloomsbury.

Schneider, Rebecca, and Lucia Ruprecht. 2017. ‘In Our Hands: An

Ethics of Gestural Response-Ability. Rebecca Schneider in Conversation with

Lucia Ruprecht’. Performance Philosophy 3 (1): 107–24. https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2017.31161

Schwan, Alexander. 2017. ‘Ethos Formula: Liturgy and Rhetorics in the Work of Ted Shawn’. Performance Philosophy 3 (1): 22–38. https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2017.31168

STUK. 2017. ‘Programme: Maybe This Act, This Work, This Thing

(Joachim Koester)’. STUK. Accessed May 5.

http://www.stuk.be/en/program/maybe-act-work-thing

Tinius, Jonas. 2015. ‘Aesthetics, Ethics, and Engagement:

Self-Cultivation as the Politics of Engaged Theatre’. In

Anthropology, Theatre, and Development: The Transformative Potential of

Performance

, edited by Alex Flynn and Jonas Tinius, 171–202. Basingstoke:

Palgrave Macmillan.

https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137350602.0017

Webber, Andrew J. 1996. The Doppelgänger: Double Visions in German Literature.

Oxford: Clarendon.

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198159049.001.0001

Biography

Lucia Ruprecht is an affiliated Lecturer at the Department of German and

Dutch, University of Cambridge, and a Fellow of Emmanuel College. Her

Dances of the Self in Heinrich von Kleist, E.T.A. Hoffmann and Heinrich

Heine

(2006) was awarded Special Citation of the de la Torre Bueno Prize. She has

co-edited Performance and Performativity in German Cultural Studies (with

Carolin Duttlinger and Andrew Webber, 2003), Cultural Pleasure

(with Michael Minden, 2009) and New German Dance Studies (with

Susan Manning, 2012). From 2013 to 2015, she was an Alexander von Humboldt

Fellow at the Institute of Theatre Studies, Free University Berlin. She is

currently completing the manuscript of a book entitled

Gestural Imaginaries: Dance and the Culture of Gestures at the

Beginning of the Twentieth Century

, under contract with Oxford University Press.

© 2017 Lucia Ruprecht

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Sometimes, the recognisability of their moves is not so much a matter

of the latter’s mimetic shapes than of their ‘effort

quality’, to use Rudolf von Laban’s term: it is with

abruptness that the dancers swing around or stop and start movement

sequences, reminding us of the hypervigilance and the speedy reactions

of gunfighters. One description speaks of a deconstruction of the Wild

West’s ‘ritualised gestures’ (Camden Arts Centre

2017), pointing up the fact that the choreography (which was created by

Koester together with the striking performers Pieter Ampe,

Boglárka Börcsök, Liz Kinoshita and Halla Olafsdottir)

takes generic gestures out of their embedding in a plot structure. It

also takes them out of their usual gender assignment, as each dancer

enacts a vocabulary that would be considered largely masculine within

the genre-framework. At the same time, displacements of genre

vocabulary across body parts produce cross-over genderings: the

circling wrist movement of (a man’s) lassoing returns in the

undulations of a woman’s hips. For Noland, gesturality consists

not least in the fact that ‘movements of all kinds can be

abstracted from the projects to which they contingently belong’,

so that, ‘accordingly, they can be studied as both discrete units

of meaning and distinct instances of kinesis’ (2009, 6).

Koester’s video installation incites this kind of study. Detached

from their sites and props, from their usual operationality and from

narrative context, his gestures are performed in a space that is

similarly abstracted, segmented by loosely mounted wooden walls which

suggest make-shift cabins. The soundscape is denaturalised, amplifying

the inhales and exhales of breath, the shuffling of feet, and muffled

blows. A form of muffling also affects the field of the visual, with

the dancers moving in and out of shallow zones of focus, and even

moving in and out of camera frames, as if each medium shot defined a

new stage-like square.

Sometimes, the recognisability of their moves is not so much a matter

of the latter’s mimetic shapes than of their ‘effort

quality’, to use Rudolf von Laban’s term: it is with

abruptness that the dancers swing around or stop and start movement

sequences, reminding us of the hypervigilance and the speedy reactions

of gunfighters. One description speaks of a deconstruction of the Wild

West’s ‘ritualised gestures’ (Camden Arts Centre

2017), pointing up the fact that the choreography (which was created by

Koester together with the striking performers Pieter Ampe,

Boglárka Börcsök, Liz Kinoshita and Halla Olafsdottir)

takes generic gestures out of their embedding in a plot structure. It

also takes them out of their usual gender assignment, as each dancer

enacts a vocabulary that would be considered largely masculine within

the genre-framework. At the same time, displacements of genre

vocabulary across body parts produce cross-over genderings: the