Being in Touch: A metamorphosis of Jan Fabre’s The Castles in the Hour Blue into bodies of longing

Sylvia Solakidi, Center for Performance Philosophy, Surrey UK

for Λ

“Time is the substance I am made of.

Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am

the river;

it is a tiger which destroys me, but I am the

tiger; it is a fire which consumes me, but I am the fire.”

Jorge Luis Borges, “A New Refutation of Time”

A green light has sprouted in a small circle at the lower right

quadrant of her photograph. She is “active now.”

The pattern of dark photographs and those with bright green

circles changes continuously on the rectangular window of the

messenger application that is open while I write on my laptop.

Each light bears potential for a contact.

When did all these lights emerge?

As I am sitting at my writing table and I move my eyes from the

rectangular laptop screen to my rectangular window, I see the

rectangular sky segment cloudy and the lights on in several

rectangular windows of the rooms at the opposite side of the inner

yard; each light indicates human activity. The pattern of dark and

bright rectangular elements changes continuously, following the

weather and the hours of the day. The time that passes becomes a

kaleidoscopic installation of flashing lights that I cannot

affect; I cannot affect time, as I cannot contact people and

participate in their activities. An Empire of Light in

the inner yard.

In the old times, we touched each other and it was only Mr Monk

who needed antiseptic wipes after human contact. In the old times,

we were active with others outside our homes and it was only Mr

Monk who believed that “it’s a jungle out there.” This is the

title of Randy Newman’s song for the titles of the TV series about

the brilliant detective who suffered from phobias that worsened

after the loss of his beloved wife. Since March 2020, it’s a

jungle out there for everyone; the COVID-19 pandemic jungle. In

order to protect each other we must practise social distancing.

Our homes are shields from the virus and isolation is the price we

pay for safety; we trade human contact for safety. Touch is

related etymologically to both contact and contagion (Partridge

1991, 692); touch, though, has become dangerous, as if it was

related only to contagion and not to contact.

Despite a distance of no more than a few metres, people and

their activity around the inner yard are beyond my reach. My need

not to lose touch becomes more pressing with time; I am near but

not close enough. I am like Tantalus, who saw trees and rivers

withdraw, as he stretched his arms to grab fruits and drink water;

he could see what he could not have. As I am sitting at my writing

table and I am looking out of the window, the unbridgeable

distance of safety brings despair; I acquire the desperate body of

Tantalus. I can only be in touch with people online. Distance

depriving me from human contact in the physical space and

transforming contact in the digital space becomes a limitation in

my life.

The old times of touch as contact rather than contagion were

only over a year ago.[1]

Experts talk about the post-pandemic era, a new era of human

relationships. Old times bring nostalgia and post-pandemic brings

uncertainty. The distance in space that isolates one from others

is transformed into a distance from time, as I am isolated from

both past and future; I close down into a parenthesis of time. The

notion of post-pandemic implies a future as succession and

completion, a future of evolution, which closes the door behind it

and sets an unbridgeable distance from the past, the old times

when touch as contact was possible. If I lose touch with contact

and I offer touch to contagion, this parenthesis will never open

again and contact will be confined to an unreachable past.

Certainly, quarantine and physical distance are needed during the

pandemic. But why should physical distance become social and

temporal as well?

As I am sitting at my writing table, I try to make sense of my

unprecedented isolation. I read Marc Augé’s 2014 book The

Future and I realize that the future of post-pandemic is

not the only option. The future, he claims, is “a time of

conjunction,” which “always has a social dimension” and “depends

on others,” so that we may not lose touch (Chapter 1). The

parenthesis of time will make the past of touch as contact

“disappear and collapse” and will bring more “solitude in the

blank image of a terrifying future” (Chapter 2). Augé’s notion of

the future as “inauguration,” a “beginning” and a “birth” (Chapter

3), suggests that the transformation of touch from contagion into

contact can only happen during the pandemic, otherwise loss will

be irrevocable.

As I am sitting at my writing table and I am looking at the

succession of day and night in the changing pattern of lights in

the rectangular elements on my screen and outside my window, I

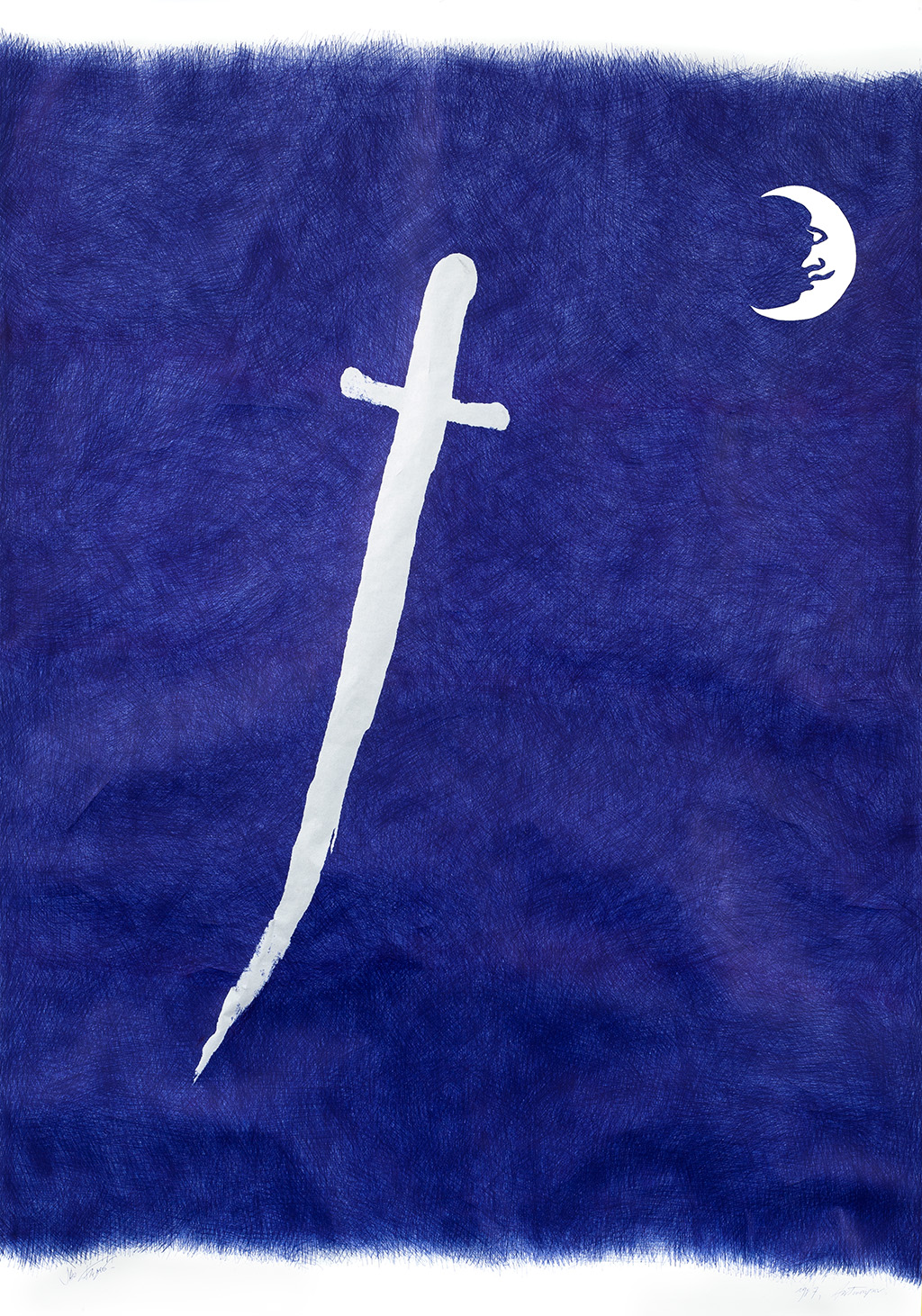

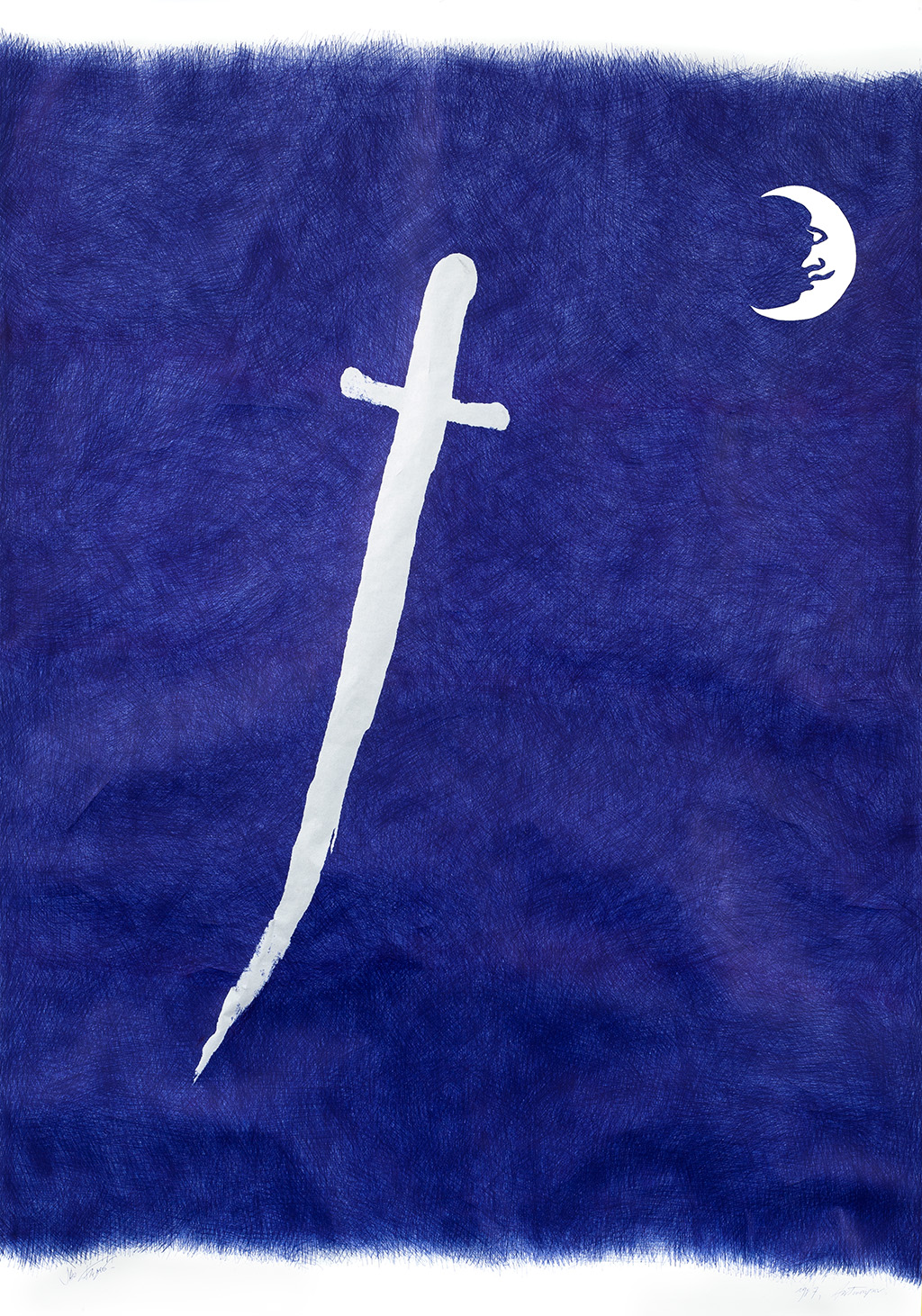

re-view an image of day and night, light and darkness, from the

old times. On a gallery wall, two rectangular drawings are hung

side by side; the day and the night, the sun and the moon, a cross

for the sun and a sword for the moon, among blue lines that cover

the surface of the drawings. Let’s follow the blue lines; where

did they stem from?

Figure 1a: Jan Fabre Cross with suns

(1987). Bic ballpoint pen on paper 238 x 165 cm. Photo: Pat

Verbruggen. Copyright: Angelos bv.

Figure 1b: Jan Fabre Sword in

the night (1987). Bic ballpoint pen on paper 238 x 165 cm.

Photo: Pat Verbruggen. Copyright: Angelos bv.

***

In the beginning was an insect. In the late 1970s, in Antwerp,

Belgium. On a white paper sheet on the top of the work table of a

young artist. What time is it? It is the Hour Blue, the time of

stillness and silence, when nocturnal animals have gone to bed and

diurnal animals are not yet awake (Bernadac 2008, 104). The Hour

Blue is a hybrid of night and day. It is not “night” since

nocturnal animals are not active; it is not “day” either, since

diurnal animals are not active. It is like an Empire of Light,

René Magritte’s series of paintings with a paradoxical combination

of a day sky with a night earth. It is the time of sleep and

transformation from night to day; it is “the hour of imagination”

(van den Dries 2001, 61).

The artist is the great nephew of the entomologist Jean-Henri

Fabre who defined the Hour Blue. And the insect was with the

artist, with Jan Fabre, who is awake and works at his table. He

was intrigued by the insect’s movement on paper and he traced it

with a blue BIC ballpoint pen (Fabre and Bekkers 2006, 23–24); he

wrote movement down. More BIC blue lines followed; the white paper

became blue with white gaps since the pen can never cover the

surface smoothly. “There is a land where drawing is writing and

vice versa […] This land lives in me and I have discovered it

through Vincent van Gogh,” Fabre writes in his diary (Fabre 2011,

15). The BIC blue lines are vibrating like those in van Gogh’s

paintings. As the Hour Blue, the hybrid of night and day, is drawn

in BIC blue pen, which is a writing instrument, each work becomes

a hybrid of drawing and Fabre’s handwriting. Out of the repetitive

BIC blue lines emerge letters, words and forms, either in blue or

in white—cuts on paper or spaces untouched by BIC, like the sun,

the moon, the stars, the sword and the cross in the works Cross

with Suns and Sword in the Night [Figures 1a and

1b]. Drawing and night are not closed down into themselves, but

open up towards writing and day, their supposed opposites.

The process of transformation from egg to adult during the life

cycle of an insect is called metamorphosis. And since an insect

triggers the drawing of the first line of Fabre’s Hour Blue, it

transforms it into an hour of metamorphosis. For Fabre, who stages

repetition in his visual and performing art, the biological

process of metamorphosis has become “an attitude in life” (van den

Dries 2001, 60). Repetition that allows the body of the artist “to

master the action” (59) is his condition for endless

experimentation (Fabre 2011, 134) and is derived from what he

considers to be the main principle of theatre that repeats itself

differently in each rehearsal and performance of a piece (Fabre

2011, 132). In Flemish, his language, the word “repetitie” stands for both repetition and rehearsal (van Dale 2008).

Metamorphosis for Fabre becomes the opening up towards new

experiences; it is a birth. Each repetition is different than the

previous one, like the forms of the body of an insect during its

life cycle. Each repetition is metamorphosis in-the-making, a

process towards a future (Fabre 2011, 139), which can be

inauguration and new beginning, according to Augé.

As I am sitting at my writing table, I try to make sense of my

unprecedented isolation from people and time by approaching the

future through Fabre’s staging of the biological notion of

metamorphosis. He is not alone in this process. In his 2021 book Metamorphoses,

philosopher Emanuele Coccia also reflects on metamorphosis as a

concept not confined to insects and their biology but as a

principle of “shared life” (174). He approaches metamorphosis as

an alternative to “evolution and progress” (9), since the

different forms of an organism do not replace one another but are

“simultaneously present and successive” (9), comprising “a

continuity of life” (3). He claims that metamorphosis is rather a

life of forms than a form of life” (54). “A single self expresses

itself” across forms (57) and none of them corresponds to a final

stage of an evolutionary process; metamorphosis is always

in-the-making. “Every living being is a chimera” of more forms,

states Coccia (55). Accordingly, Fabre privileges metamorphosis

because he “refuses to accept the body as a closed identity” (van

den Dries 2001, 66). Bodies on his stage are “hybrid,” hence

“liquid” and “rebellious,” and cannot be easily kept under

control, as they change form continuously. The Hour Blue that is

initiated by insects as a hybrid of night and day, as well as

writing and drawing, is for Fabre the hour of metamorphosis,

because the body can open up from its presumed “unique” identity

(61).

How about the body of Tantalus and its closed identity of

desperate isolation? Could it open up through a metamorphosis? As

I am sitting at my writing table, I re-view my experience of

Fabre’s Hour Blue drawings.

It is December 2018 in Milan and I visit Fabre’s exhibition The

Castles in the Hour Blue (22.09–22.12.2018) curated by

Melania Rossi in Building Gallery and Basilica of Sant’ Eustorgio.

The choice of the church does not come as a surprise. Fabre has

been influenced by the spirituality of the works of Great Masters

in Antwerp, his home city. He has even created works that are

permanently housed in Churches, such as his sculpture The man

who bears the Cross in the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp

and his installations with hearts made of red coral in the Chapel

of Pio Monte della Misericordia in Naples. As I look at the works

and I am taking down notes in BIC ballpoint pen, I keep my hands

busy, with a pen and a notepad, while my hands are eager to touch

the works. These drawings with the blue lines that scratch the

paper deep and create a relief surface are like “parchment or

prepared skin,” as Fabre states (2014, 158). Their protective

glass makes the distance from the skin of my hands to their “skin”

feel bigger; I am near but not close enough. I am desperate to

touch the works, I long for this touch. The inviting, tactile

characteristics of these drawings, though, can be perceived with

my eyes; my eyes touch them. It is not the torture of Tantalus. It

is a game of the senses. The distance between our skins is part of

this game, it makes the experience of drawings more intense, as I

am on the verge of touching the works and my imagination is

triggered by involving two senses, vision and tactility, instead

of tactility alone. The viewing experience of the drawings of the

hybrid Hour Blue becomes a hybrid of two senses, a sense

in-the-making, a metamorphosis of my senses and my viewing

experience that allows me to be in touch with the drawing without

touching it.

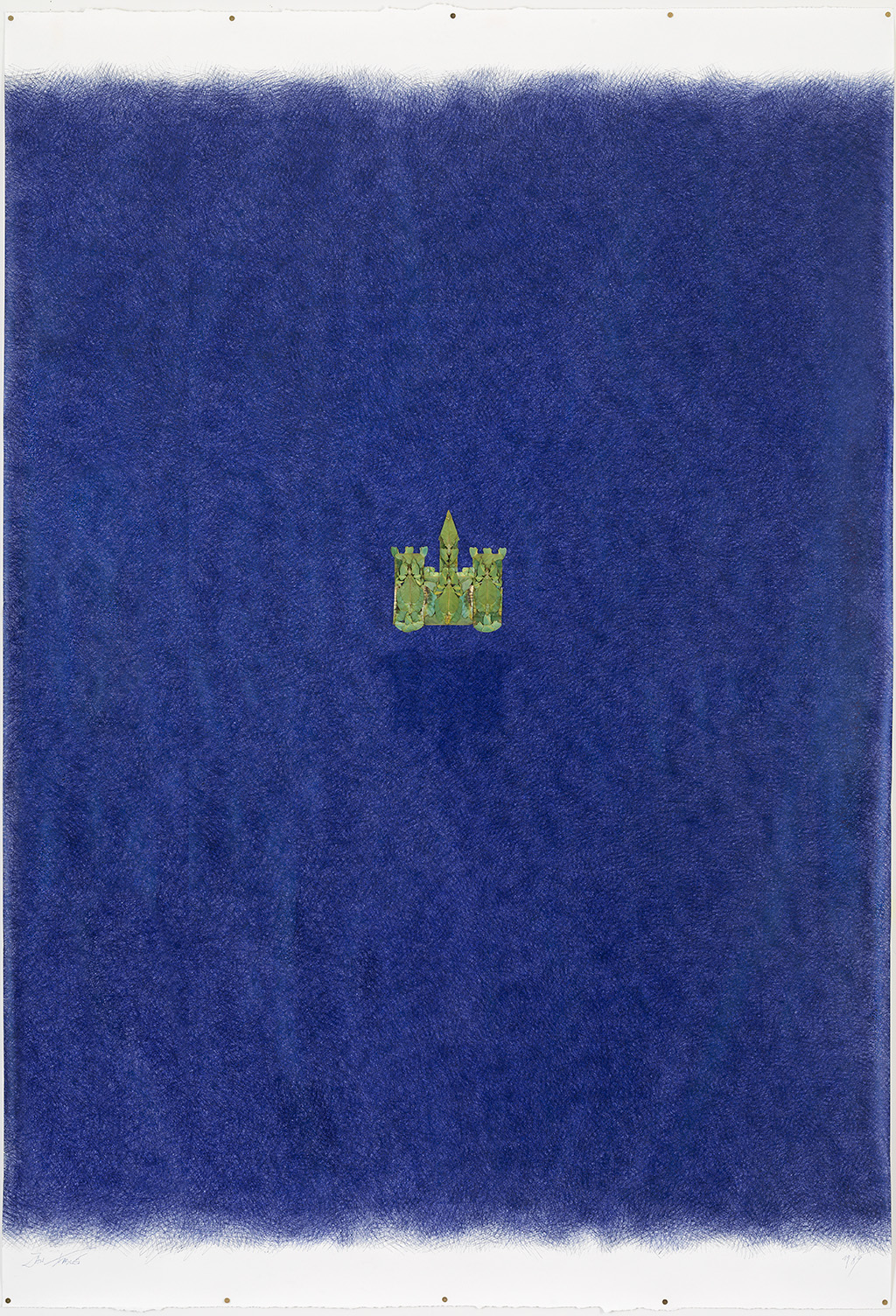

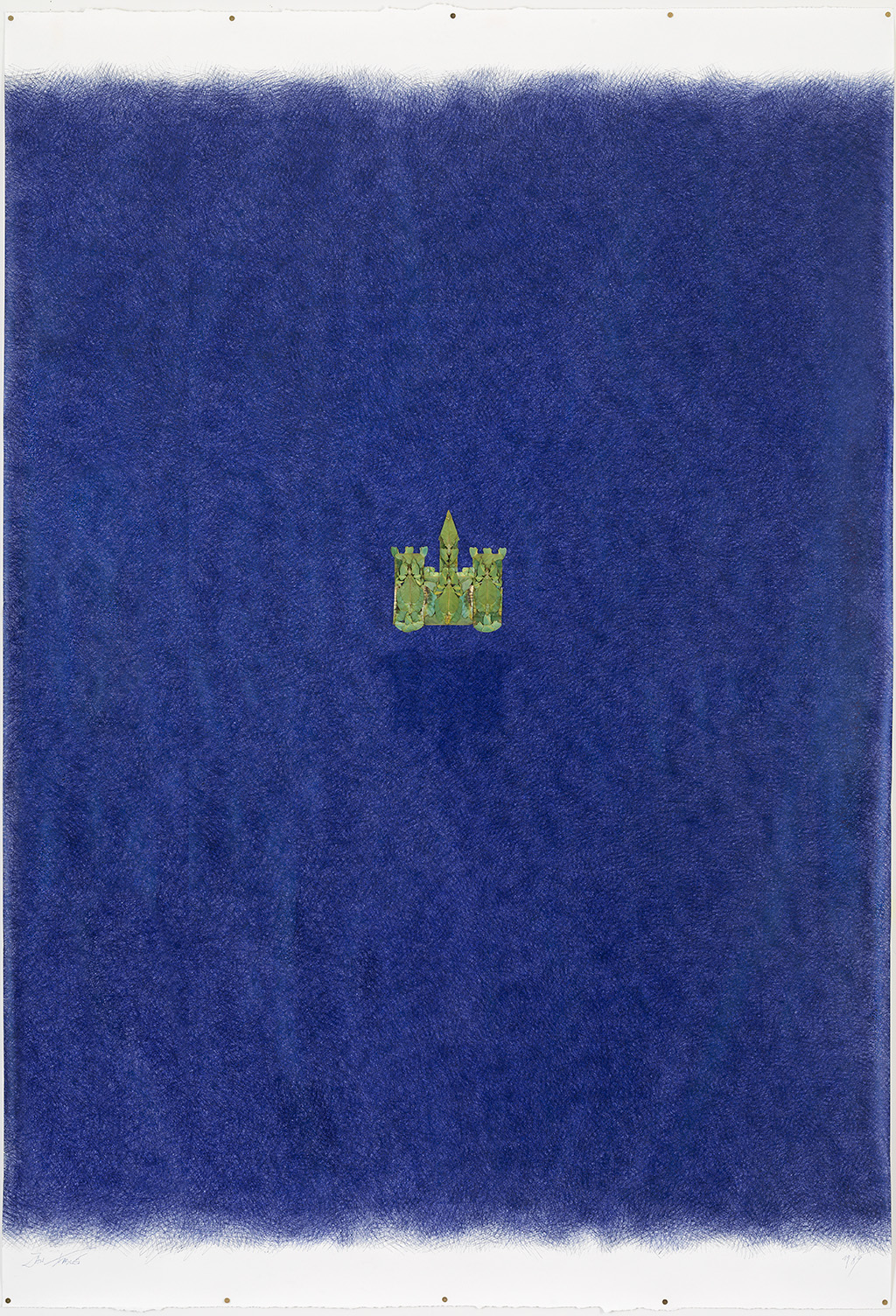

In a series of 1989–1990 drawings, castles made of plant leaves

are placed on the BIC blue lines (Figure 2). No, these are not

leaves, they have antennae… and six legs. They are insects! The

castles are made of bodies of Phyllium giganteum, an

insect species that has a hybrid phenotype and resembles a plant

leaf. These insects undergo metamorphosis to leaves and castles by

crossing over the limits of species and living organisms; they are

hybrid creatures of the Hour Blue. They tend towards the BIC blue

lines, they long for them, but are never fused with them. They are

added on the relief as distinct bodies that interact with the

“prepared skin,” they organize and orient the vibrating BIC blue

lines around them, and they shape their Hour Blue

through their BIC blue shadow. The intensity of the interaction

between castles and BIC blue lines adds to the intensity of my

viewing experience of the drawing’s tactile features.

Figure 2: Jan Fabre Dream castle in the hour

blue (1989). Bic ballpoint pen on paper with pieces of Phyllium

giganteum 168,2 x 164,5 x 6 cm (incl. frame). Photo: Pat

Verbruggen. Copyright: Angelos bv

These castles are not made of stone but of bodies of insects;

life is their building stone. More precisely, “shared life”

(Coccia 2021, 174), since insects offer them their process of

metamorphosis. For Fabre, insects are “comparable to medieval

knights,” since their exoskeletons are like armour. He believes

that an armour protects the vulnerability of existence and he

embraces metamorphosis as a way to expose and protect this

vulnerability (Bernadac 2008, 105). “The medieval universe” is a

place “where the opposites coexist,” he states. His example is the

brave Lancelot, who has an imperfection since he commits adultery.

Like a medieval knight, the insect is “hard and vulnerable” (32).

The castles in the Hour Blue are such hybrids; they are vulnerable

shields. The Hour Blue, the hybrid that is fluid and cannot be

controlled, can protect as well.

In Basilica of Sant’ Eustorgio, Fabre’s 1987 piece on artificial

silk A Castle in the Sky for René (Figure 3) was hung

like a soft wall, along the left aisle of the main body of the

church, where the Mass takes place. There are no insects in this

piece. Out of the BIC blue lines emerge various forms. As I was

about to light a candle at the chapel opposite this work, I saw a

heart; it was the main form at the upper right part of the piece.

No, it is not a heart; it is a rock, the building stone of the

castle. The piece is dedicated to René Magritte, the Belgian

painter who used to paint rocks, as well as skies, like the day

sky over the night earth in his series Empire of Lights,

and Fabre considers him to be one of his Masters. The information

next to the piece pointed to my mistake; still, I looked at the

piece and its heart was beating. A metamorphosis of the rock into

a heart took place in my viewing experience. The castle founded by

this rock is a vulnerable shield, a castle in the Hour Blue,

because its beating heart is an invitation for a contact with

those who are outside. This castle offers security not because its

rocks are as strong, but because it longs for contact. A castle

can be seen from everywhere, but life inside is inaccessible; it

is closing down and it is always ready for defence. This castle,

though, shows its beating heart and opens up, it refuses isolation

and suggests that protection is connected to interaction. In the

Hour Blue of metamorphosis, safety undergoes a metamorphosis and

the knight of the castle made of stone/heart is desperate for

others; he longs for contact.

Figure 3: Jan Fabre A castle in the sky for René

(1987). Bic ballpoint pen on artificial silk 689 x 1684 cm. Photo:

Installation during the exhibition ‘Jan Fabre. The Castles in the

Hour Blue’, Milan, 2018. Location: Basilica of Sant’Eustorgio,

Portinari Chapel. Photo: Atiilio Maranzano. Copyright: Angelos bv

And there was evening, and night is not the end of the day for

Fabre, but the beginning. The Hour Blue is his time of creativity,

when he makes his drawings and writes in his diary; he uses BIC

pen for both, as “despite the computerized world, he writes

everything by hand” (Lórán 2012, 140). “Whom can I count on?” he

asks in his Night Diary (Fabre 2011, 129). His diary is

intimate, a way to close down into his thoughts, but he longs for

interaction with others, he is desperate to open up during the

day; he has also published his intimate diaries.

He works in his home that is lit not only by electricity, but by

his creativity as well; it becomes a House of Flames, of

BIC blue vibrant flames, like the houses of his 1989–1991

installation—three rectangular boxes painted in BIC blue and a

bigger one, a “Tower,” at the end. The first box has its door

closed, the other two have their doors open at different degrees,

while the Tower’s door is wide open (Figure 4). This installation

is a hybrid of different stages of closing down and opening up; it

demonstrates metamorphosis in-the-making. I did not see this

installation in Milan. The Castles in the Hour Blue is a

touring exhibition but undergoes metamorphosis, as the curator

adapts it to each exhibition site. I saw this piece in Arras,

France, in Musée des beaux Arts, the old Benedictine Abbey of

Saint Vaast, where it was scheduled to run from 02.03.2020 to

04.05.2020, but closed early because of the COVID-19 restrictions;

I visited it on its second day, to re-view the works that I had

already enjoyed in Milan.

Figure 4: Jan Fabre Houses of flames (shrines)

(1988). Bic ballpoint blue on wood (three parts) 17 x 20 x 29 cm;

25 x 28,5 x 39 cm; 32 x 37 x 51,5 cm. Photo: Pat Verbruggen.

Copyright: Angelos bv. Jan Fabre Houses of flames (tower) (1991).

Bic ballpoint blue on wood 76 x 24 x 32 cm. Photo: Pat Verbruggen.

Copyright: Angelos bv

And there was morning and Fabre met people he could count on.

And with them he made the work Tivoli (1990), and

covered the walls of this castle with Hour Blue BIC drawings that

he prepared with friends and colleagues. The paper sheet of his

Hour Blue drawings has opened up and has become immense; he is

sharing the life of his Hour Blue with others. And others

re-create the Hour Blue with him. And others look at the works;

like me, who looked at photographs and film of the Tivoli castle

in his exhibition in Milan and Arras. His creativity of the night

undergoes metamorphosis and becomes a hybrid with the creativity

of others during the day.

And there was morning and Fabre met people he could count on.

And with them he makes theatre. During the night he prepares

himself for the rehearsals of the day by writing and making

drawings (Fabre 2011, 140); he prepares himself for the

metamorphosis of his creative rituals of the night into the

rituals in his rehearsal space, Troubleyn Laboratorium, in

Antwerp. “Ritual is essentially a birth,” as Augé insists, and

theatrical rituals are only possible with others. The

collaboration in Fabre’s theatre Laboratorium is also based on

metamorphosis, as Fabre believes that there is “one long chain

that keeps us all together” (van den Dries 2001, 61). The

biological fact that “our life […] was transmitted to us by

others” and that it is “a continuation and a metamorphosis of a

life that came before it” (Coccia 2021, 3–4), is transformed into

theatre. The paper sheet of his Hour Blue drawings has opened up

and has covered the stage of his first opera, The Minds of

Helena Troubleyn and his theatre piece Prometheus

Landscape I, after Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound

in the 1980s. The knight has admitted his vulnerability by showing

the beating heart of his castle, his own beating heart, and he

longs for sharing his activities with others. He opens the door

gradually, with caution, Safety is not achieved in total

isolation, but in cautious interaction with others. Fabre closes

down for preparation in order to open up for collaboration,

towards a future as birth and “conjunction,” as Augé states, which

materializes in his theatre pieces. A castle in the Hour Blue can

be a shield for the preservation of contact; the invitation to

shield together and protect each other.

***

In the beginning was an insect and the insect is Fabre. He is

the dung beetle, “the happy Sisyphus” of repetition. He identifies

himself with the beetle that rolls a huge ball to the peak of a

hill and lets it roll back in order to collect materials and do

the itinerary again, differently (Fabre 2002). And as an insect he

can undergo metamorphosis into a castle; he becomes a

castle in the Hour Blue.

And there was evening. In his House of Flames, Fabre cannot

sleep. He is an insomniac, “he lives the night in a continuous

manner” (Fabre and Bekkers 2006, 21). As a result, he is awake

when both nocturnal and diurnal animals sleep and he experiences

the Hour Blue. He does not only observe the Hour Blue, but he

shapes it, he makes it his own, as the BIC blue lines are directed

towards the lower right corner of the paper and give rise to his

signature; his name becomes another bunch of vibrant BIC blue

lines. As he undergoes the metamorphosis of Hour Blue every night,

he becomes the Hour Blue.

According to Coccia, “being alive does not just mean perceiving

the world […] but also constructing it, shaping it in a different

way” (155). Fabre reflects on his insomnia and explains it

creatively: “Why don’t I sleep? Because only during the night I

have the time to be who I am” (2011, 20). He approaches sleep

deprivation as a creative limitation and as he is both a Castle and

the Hour Blue, he copes creatively with time, in a way that

differs from those who can sleep. The Hour Blue, his time of

“imagination,” becomes his time of creativity because he dares to

cope creatively with its temporality.

Since his childhood, he has been building castles and listening

to chivalry stories from his father (Fabre 2011, 99). Fabre has

been dreaming to restore chivalry as a fight for a good cause

(2014, 37). The knight of despair is the main character in his

2005 theatre piece History of Tears. The knight achieves

a metamorphosis of his desperate situation, from loss of hope to

longing for something, as despair makes him believe “in an absurd

hope” (Fabre 2005, 31). This knight has a special relationship

with temporality, as he says “I sense the future” (11). The good

cause that he fights for is the search for a future through

relating to people, those who are on the same stage, where he

performs his monologues at a distance. As time goes by, he

switches from “I” to “we,” when he speaks. He longs for people, as

he longs for the future that he can already sense. His sword in

this fight is “the force of vulnerability” (11). The knight is

immortal, a hybrid of living and dead bodies, since when one dies,

another takes its place (12). His body undergoes metamorphosis of

life and death and constantly changes form. It does not have “a

closed identity” (van den Dries 2001, 66), but it is “longing for

completeness” (61). For Fabre, this completeness is “the sublime

moment when scene and audience merge into a seamless whole” (61),

the moment when the insomniac artist who works alone in his room

when everyone sleeps, undergoes a metamorphosis through the

interaction with collaborators and audience.

The future that the knight senses cannot be a time that closes

down, a future of succession, but a future of a new birth. For

Coccia, metamorphosis is “a future, an omnipresent possibility.

[…] And everything leads back to it—especially death” (83), which

is “a metamorphic threshold” (90). For Fabre, “death is the father

of metamorphosis” (2007, 135). The knight of despair is a hybrid

creature of life and death on Fabre’s stage, where death longs for

life and vice versa; in his case, “two incompatible bodies belong

to the same individual” (Coccia 2021, 174). Death, the

vulnerability of existence, is not the end but the longing for a

future of a new birth.

Fabre who experiences the night “in a continuous manner,” like

the immortal knight experiences life and death “in a continuous

manner,” explores his insomniac body as a body that undergoes

metamorphosis, as a Castle in the Hour Blue. The vulnerability of

his insomniac body becomes his strength, like the exposed

vulnerability of the beating heart of the Castle of the Hour Blue.

Alone in the night, he creates rituals to cope with his insomnia.

These rituals undergo metamorphosis in his theatre space,

Troubleyn Laboratorium, his other “castle,” with his performers in

the morning. This Laboratorium is a shield for an artistic

community, “a sheltered building” (Bousset et al. 2016, 79). The

hybrid body of metamorphosis re-creates the Hour Blue by coping

creatively with its temporality through despair that longs for a

future of “an absurd hope;” a future through longing.

I went to Arras in March 2020 to watch Fabre’s solo theatre

piece Resurrexit Cassandra (2019), and his exhibition The

Castles in the Hour Blue was opening on that day. His

Cassandra is a hybrid creature of life and death, the prophetess

who comes back to life in order to warn humans about climate

change; she is a hybrid creature of the Hour Blue, although no BIC

blue lines cover the stage like in Fabre’s theatre works of the

1980s. On my last time in the theatre and in a museum before the

pandemic, I heard a plea for metamorphosis as a future through

longing. As I am sitting at my writing table, I re-view the

exhibition that I visited twice, through this plea. Since

metamorphosis is a process of repeating differently through

hybrids, I take up Fabre’s gesture and I explore it through the

dynamics of closing down and opening up. It is not a narrative of

evolution, my writing does not progress, but unfolds in rounds of

closing down and opening up that repeat this movement differently

in the art of Fabre and my experience of isolation; it creates

hybrids of these two states instead of opposing them to each

other. The beating heart and the open door of Fabre’s castles are

an invitation to share his creativity, an attempt to cope

creatively with time that will lead to a future through longing.

It is a narrative of a future as birth, a narrative of genesis of

a temporality that takes up the genesis of Fabre’s universe of the

Hour Blue. It is told with the help of the Book of Genesis and the

beginning of the Gospel of St John, an attempt of a secular

metamorphosis of a sacred narrative, like the one performed by

Fabre in his works that are in Churches.

I re-view Fabre’s exhibition in order to hybridize my experience

from the two visits with the experience of the pandemic. Art can

become a paradigm for shaping a future, since, as Augé claims,

“art offers to one and all the opportunity to live through a

commencement.” This experience does not end when I leave the

exhibition space, I can adapt it in order to live. Whom can I

count on? If touch is not closed down in a parenthesis of time

during the pandemic but becomes a hybrid of contagion and contact

by taking its vulnerability into account, this sense can undergo

metamorphosis and lead to a future through the hybrid temporality

of longing, since when I long for something, I experience in my

present a future birth.

As I am sitting at my writing table, I watch a recording of

Penny Arcade’s performance Longing lasts Longer

(Zehentner 2021), a performance that I experienced in London in

2016. “Longing is a persistent sense of loss that attaches to

ourselves,” states Arcade. Longing is not nostalgia, since

“nostalgia is done from a safe distance,” according to Arcade, but

touch is not trapped in the old times that can only be missed, but

is opening up towards the future of a new birth. As a hybrid

temporality, “longing lasts longer, longer than anything else,” as

Arcade keeps repeating, since it does not close down into one

point in time. It is immortal like the knight of despair, and

takes different forms; longing is constantly born anew. Longing

can make metamorphosis happen because it prepares for it. As I am

sitting at my writing table, I read the novella Mokusei!

by the Dutch writer Cees Nooteboom: “When does such a thing as a

great love begin? [...] probably started with the longing for one

[…] That had been the preparation for the moment” (50). For the

moment that Fabre’s theatre company meet their audience in theatre

venues; for the moment that quarantine will end.

Longing is related to length, to distance in space and time of

waiting. When Fabre closes down in his home during the night, when

BIC blue lines cannot cover the paper smoothly and when I cannot

touch the drawings, distance does not lead to disruption of

experience but to its metamorphosis into creativity. Distance from

others, which is essential to keep us safe from the pandemic, can

be approached as a creative limitation, the way Fabre is coping

with his insomnia. As I am sitting at my writing table, I re-view

the exhibition in order to explore the possibility of a

metamorphosis of my body of the desperate Tantalus into a body of

longing. Fabre achieves metamorphosis, can I do the same?

Although the distance of a few metres among windows in the inner

yard seems unbridgeable, we can be in touch online by seeing each

other. We can change our point of view on time and refuse to

experience the pandemic as a temporal parenthesis in our lives.

Instead of leaving contact in the past, we may take advantage of

the fact that we can be on the verge of touch thanks to technology

and approach it as an opportunity which makes things more intense

and urgent. Longing becomes a pressing need for action when there

is a limitation. When touch was possible and I could not imagine

that I could be deprived of it, the viewing of Fabre’s exhibition

where touch was not allowed prepared me for it as I coped

creatively by experiencing the tactile features of drawings

through a hybrid sense of vision and touch. I was “long-prepared”

for the loss. This long preparation is called longing, a longing

for loss, by Leonard Cohen in his Book of Longing

(60–61) where he made his own metamorphosis of the poem “God

abandons Anthony” by Constantine Cavafy. The hybrid temporality of

longing extends to a past that is not nostalgia. When longing for

something, we are in touch with the whole temporality instead of

suffering inside a parenthesis of time; being in touch with time

prepares for being in touch with people.

The distance mediated by screens during a video call may

activate the game of the senses, since my gaze has been prepared

to long for tactile characteristics and the touch of skin, like

the “prepared skin” of Fabre’s drawings. In the same exhibition

space, my gaze was also prepared to touch the skin of the castle

of Tivoli, through photographs and a film. The prepared gaze does

not only perceive tactile characteristics but also creates and

changes its environment, an act that also “changes the environment

of others,” as Coccia suggests (156). Thus, the intensity of being

on the verge of touching people, leads to a metamorphosis of the

sense of touch, so that people who are in touch through screens

may participate in each other’s activities through the mutual

creation of an environment of shared life defined by longing to

touch and be touched.

French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty proposes “the flesh

of the world” as the ontological element that guarantees the

intertwining between our bodies and the world thanks to

reversibility (1968, 147), the intertwining between the body and

the world as well as between senses. Since our bodies are nodes in

the fabric of this flesh of the world, they are open to the world

and our gazes “envelop” things and bodies (131). This

reversibility makes possible the game of the senses that leads to

the hybrid sense of vision and touch. Merleau-Ponty grounds

intersubjectivity on reversibility. He describes the relationship

that we have with our own bodies not as a relationship with an

object but as a reversibility of touching and being touched: when

my two hands touch each other, each of them is both touching and

being touched from the other (1964, 166). Intersubjective

relationships happen as intercorporeal relationships when the two

hands do not belong to one body, but two: “The handshake too is

reversible” (1968, 142). Through longing I can have something

without possessing it, unlike Tantalus, who sees what he cannot

have. Others are not near but are close enough. The challenge for

which longing prepares us during the video calls is to move from

gazes that touch to touching each other; to move from having

without possessing to grasping each other’s hands.

When the digital distance is approached as a creative limitation

that may change the environment of experience, it can transform

the restrictive function of distance in the physical space as

well. The lights from the rectangular windows in my inner yard can

create the longing that has been practised online, so that I may

not be shut outside the lives of others but participate in their

activities through having without possessing them. Such

participation is possible not by visiting them, which is not safe

during the pandemic, but by realizing that by turning on and off

the light in my room I change my environment as well as theirs, as

Coccia claims (156). The light of my rectangular window is not

outside but a part of the changing pattern of lights that I

observe and corresponds to time that passes. Indeed, I can only

see one of the four sides of the rectangular inner yard and the

kaleidoscopic installation of flashing lights includes all four

sides; someone on the opposite side perceives my window as part of

the kaleidoscopic installation. Therefore, time is not outside my

room, it does not pass without me being able to have an effect on

it.

Creative coping with distance, closing down in order to open up,

leads to creative coping with time. My body is not the body of

Tantalus anymore, since by opening up towards the activities of

others it becomes a body in the course of metamorphosis, a hybrid

of temporalities of contact; the present of longing for the future

of a new contact. Longing defines my present experience and makes

it more intense, as I am not dreaming of the moment of contact

with people, but I am already in touch with them and their

activities. This also means, though, that my existence is

overwhelmed by longing; the same as metamorphosis as co-existence

of opposites and new birth is not smooth, longing involves risk.

Being desperate is not only related to loss of hope but to

willingness for great risk as well (Partridge 1991, 168). Longing

prepares for a future birth through a hybrid of vision and touch;

it does not guarantee its advent. Being on the verge, the

experience of urgency allows me to prepare to move “from longing

to skin” (Cohen 2006, 68) by opening up towards a possibility.

“Longing lasts longer than anything else,” as Arcade keeps

repeating, because opening up lasts longer. Or in Merleau-Ponty’s

words: “so long as we are alive, our situation is open” (2012,

467).

What time is it? I do not need to look at my laptop’s clock; it

is the hour of metamorphosis, the hour of longing, the Hour Blue

of the future of birth. By changing point of view upon distance,

protection not only from the pandemic but also from isolation from

past and future are achieved; only together may we protect each

other, only together may we have a future. Thanks to distance I

can become a hybrid body of longing, a body that risks the hope of

the knight of despair. I can become a Castle in the Hour Blue and

shape my Hour Blue, this essay that proposes the

temporality of longing.

***

Her green light has sprouted.

“Why are you active so late at night? Are you all right? How

about a brief chat? ... I am still sitting at my writing table,”

is my message to her.

And when my friend and I make a video call, we always touch each

other’s hands by touching our screens before we say good bye. The

idea was mine. It is the gesture that Mr Monk made when he watched

a video message that his beloved wife had recorded shortly before

her death. Our new ritual of longing until we meet again. As we

are longing for each other in order not to lose touch, we are

already in touch with each other.

Acknowledgements

The author receives funding from the TECHNE/AHRC Doctoral

Partnership

The author would like to thank Angelos/Jan Fabre for granting

permission for the publication of images of Jan Fabre’s works.

Notes

[1]

The first draft of the essay was written in London, UK during the

winter 2021 lockdown and the final version was revised in the same

London room in December 2021, when work-from-home and “be

cautious” guidance returned as a result of a surge of cases

because of a variant of COVID-19.

Works Cited

Translations from French and Dutch sources were made by

the author.

Augé Marc. 2014. The Future. London: Verso.

Kindle.

Bernadac, Marie-Laure, ed. 2008. Jan Fabre Au Louvre:

L'ange De La métamorphose. Paris: Gallimard.

Bousset, Sigrid, Katrien Bruyneel, and Mark Geurden, eds.

2016. Troubleyn Laboratorium. Brussels:

Mercatorfonds.

Coccia, Emanuele. 2021. Metamorphoses. Cambridge:

Polity Press.

Cohen, Leonard. 2006. The Book of Longing. London:

Penguin Books.

Fabre, Jan, and Ludo Bekkers. 2006. Conversation avec

Ludo Bekkers. Gerpinnes: Éditions Tandem.

Fabre, Jan. 2002. Je Marche Pendant 7 Jours Et 7 Nuits.

Paris: Ed. Jannink.

———. 2005. L'histoire Des Larmes; L'empereur De La

Perte; Le Roi Du Plagiat; Une Tribu, voilà Ce Que Je Suis;

Je Suis Une Erreur: Cinq pièces. Paris: L'arche.

———. 2007. Requiem fü r Eine

Metamorphose - Requiem for a Metamorphosis. Salzburg:

Kulturverl. Polzer.

———. 2011. Nachtboek 1978–1984. Antwerpen: De

Bezige Bij.

———. 2014. Nachtboek 1985–1991. Antwerpen: De

Bezige Bij.

Hegyi, Lórán, ed. 2012. Les années de l'Heure Bleue:

Dessins Et Sculptures, 1977–1992. Cinisello Balsamo:

Silvana Editoriale.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1964. Signs. Trans.

Richard C. McCleary. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

———. 1968. The Visible and the Invisible. Trans.

Alphonso Lingis. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

———. 2012. Phenomenology of Perception. Trans.

Donald Landes. New York: Routledge.

https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203720714

Nooteboom, Cees. 2017. Mokusei! a Love Story.

Trans. Adrienne Dixon. London: Seagull Books.

Partridge, Eric. 1991. Origins: an Etymological

Dictionary of Modern English. London: Routledge.

Van Dale Groot Woordenboek Nederlands-Engels.

2008. Utrecht: Van Dale. Kindle

van den Dries, Luk. 2001. “Jan Fabre: Metamorphology.” Interakta

4: 59–66.

Zehentner, Steve. 2021. “Penny Arcade's Longing Lasts

Longer.” Vimeo. April 19.

https://vimeo.com/groups/pennyarcade/videos/469743764

Biography

Sylvia Solakidi is at the final year of a PhD at the Centre

for Performance Philosophy, University of Surrey, which

explores contemporaneity, presence and duration in

postdramatic theatre. She has published research papers in:

Platform Postgraduate Journal, Antennae Journal,

Kronoscope Journal, Performance Research Journal,

Global Performance Studies Journal, Streetnotes

Journal, Critical Stages/Scènes Critiques.

© 2022 Sylvia Solakidi

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.