Caroline Wilkins, Independent Composer/Performer/Researcher

John Schad · Fred Dalmasso, Derrida | Benjamin, Two Plays for the Stage, Palgrave Macmillan 2021, ISBN 978-3-030-49806-1 ISBN 978-3-030-49807-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49807-8 video trailer: https://vimeo.com/503549632

Derrida | Benjamin is a remarkable volume that brings together theatre, performance and philosophy. It takes the form of an introduction by John Schad that places both philosophers within a ‘theatre of the world’ (Schad 2021, 4). For Benjamin this world is a series of tiny theatres to be found in the museum, the fairground, the puppet play, or the staircase drama enacted in an apartment building. Derrida draws much darker parallels with the world of the French insane-asylum, its inspection-and-spectacle, or the theatre of killing exemplified by acts of murder and the death camps. The two plays follow, each displacing its key philosopher to a different time/place. A conclusion by Fred Dalmasso relates the various strategies used in both plays to a context of performance philosophy. Each play, whilst reaffirming the presence of theatre within the thinking of Derrida and Benjamin, explores at the same time an underlying absence of the main character that is highlighted by these strategies.

Throughout the book certain key themes emerge that related, on first reading, to a performative context surrounding my own spontaneously awoken audio memory. References in the plays to Artaud’s theatre-world or Benjamin’s love of miniature machines, for example, evoke sounds taken from my own compositions. Sometimes I recall reading a similar ‘theatre of sounds’ to the ones described by the authors, in a work by another contemporary author, or I make analogies between techniques of film and staging, as outlined by Dalmasso in his stage notes, and those of sound. Themes such as the syncope, disruption or darkness all have parallels in terms of audio. I re-invoke ‘theatres of the world’ that are reflected in environmental sound, whether natural or machine-made, chance encounters with voices in a public building or sinister acts of eavesdropping. These sonic ‘events’ lose their original context, become ambiguous and timeless, in a suspension of narrative that allows for other unconscious associations to surface on the part of the listener. Each section of ReListening begins with a series of phrases / sentences emerging from the original content that is added to my remarks and followed by a response in sound. The sonic material itself stems from my creative archive of recordings. Specialising in the area of sound theatre, I also critique the traditional role of background sound in plays, acknowledging music and sound’s capacity to equally generate a dramaturgical argument alongside word and image. This approach results in independent lines that intersect, collide as well as support, and create multiple realities during the course of a piece of theatre.

The sections can be roughly headed as follows:The performative text,The theatre of machines and objects,The theatre of shadows and ghosts,Film and sound in theatre, The syncope, The ‘art of the impossible’ (Dalmasso 187, citing Badiou [1982] 2009, 317), and The unimaginable.

Inevitably there will be cross-references between some of these themes, but they are all linked by Dalmasso’s concluding quote from Benjamin on the statement and counter-statement that ‘displace each other in order to think each other’. Highlighted by the former as a definition of performance philosophy, it re-affirms that thought moves, shifts, goes back and forth in dialogue (Dalmasso 189, citing Benjamin 2002, 410).

Derrida as an actor in dialogue with the other. His texts are performative. The seminar as a theatre. His stage directions to self, written into the text, act as multiple voices. An actor/thinker on the stage. A process of speaking to the self / the other in/as performance.

Benjamin’s radio as a ‘Voice Land’ (Schad 3, citing Benjamin [1932] 2014, 247).

The ‘radical un-decidability of meaning’ in Artaud’s theatre, as quoted by Derrida (Schad 3) is a play (jeu) of fluidity, of suspension, of meaning as performance. I find a parallel here with the Russian Futurist language zaum, meaning ‘beyond sense’ (Wilkins 2010 / 2017). The following excerpt is taken from a poem by Alexei Kruchonyck entitled Zaum in Tiflis. Written in 1917, it reflects a break with narrative in favour of the force or weight of each vocal sound, inviting an essentially acoustic engagement with the words.

Track 1: zaum 7 (length 02:55), from Zaum: Beyond Mind, Wilkins/Ben-Tal, 2009. Reproduced with permission from the authors.

Benjamin’s love of machines as miniature theatres, their role as performers. His attachment to objects that contain a world, leaving their traces behind by haunting the stage in their presence.

The following is an excerpt from a longer work for several historical mechanical instruments that would have been familiar to the philosopher in his time. (My apologies for the unedited abruptness of the ending.)

Track 2: miniature musical box, (length 02:01), excerpt from Music for mechanical instruments, 1986, Wilkins, reproduced with permission.

Object-beings that retain a kind of memory, one that can remain in sonic form, such as the keyboard instrument that remembered all that was played upon it in D’Alembert’s Dream by Diderot ([1769] 1830).

Benjamin’s theatre of objects extends to the exterior worlds of streets or a staircase in Naples, where the scene unfolds itself. A contemporary example of this is found in the works of author Elena Ferrante such as Troubling Love (Ferrante 1992. See also Martone and Ferrante 1995).

Ghost voices that appear during the two plays. Shakespeare’s often-used stage direction to his characters: ‘Enter fleeing ’ (Schad 8). His characters draw breath and take air from the audience who become their witness. Another parallel reality occurs during performance.

Benjamin addresses radio listeners as ‘invisible’ (Schad 9 citing Benjamin [1929] 1996–2003 250); the audience performs in a theatre of hospitality, there is faith, on the part of the performers, in the shelter of audience presence:

Tracks 3 and 4: Talking Bust (length 01:58) and Windswept Angel (length 00:18), taken from the original script to The Panacousticon, 2016, Wilkins, reproduced with permission.

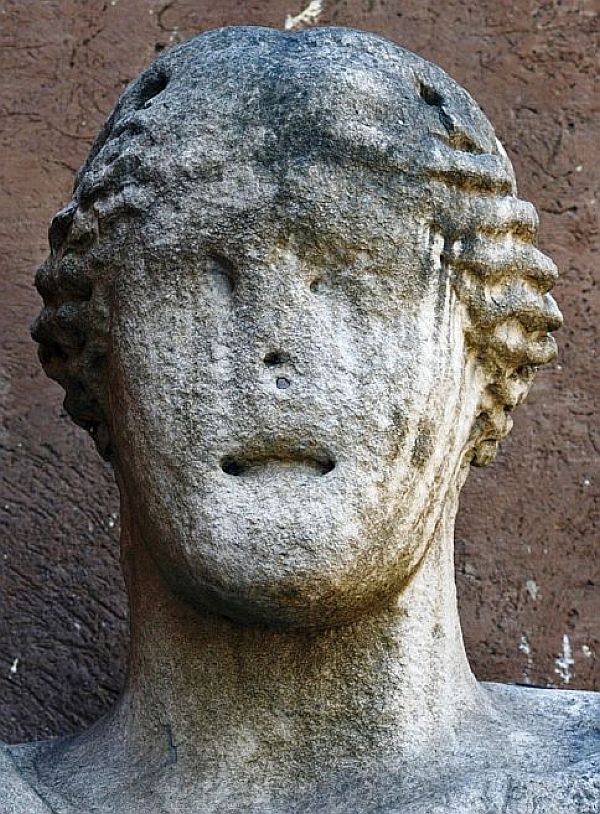

Figure 1: Madame Lucrezia, the talking statue, creative commons

Figure 2: Angelus Novus, Paul Klee (1920), creative commons.

Film plays a central role in both the content and performance of Benjamin. I compare Dalmasso’s use of film in the play’s production with sound, which can also be used in the same way as a dramaturgical device.

The original sound listed for Derrida evokes Oxford (where the play is set in 1968) and includes background sounds of WWII, the sea, clocks, telephones and steam trains. However, in my view, sound could assume more than an atmospheric role here. It has theatrical possibilities. It can be used dramaturgically in theatre as an active protagonist. It can also be distant, past, absent, but occupy the performance space as another world not visually represented.

Dalmasso’s ‘long shot’ and ‘close-up’ of film projected live on to the performance space during Benjamin evokes a ‘micro-choreography’ of limbs that dissolve into images (184). They have their equivalent in sound. For example, a change of audience sonic perception can occur through the electronic magnification (amplification) of small sound-objects onstage, transforming a microcosmic world into a macrocosmic one. The work of theatre-maker Heiner Goebbels, such as Max Black, is a perfect example of this (Goebbels 2017).

Dalmasso also uses a bird’s-eye view of the stage by placing a camera above the action, recalling, as he acknowledges, a technique used by theatre/filmmaker Lars von Trier (2022). It engenders a virtual, labyrinthine view of the stage that takes place in parallel with the live action, creating a perspective of distance, a past, an absence. This has its equivalent, for example, in the use of panoramic sound recordings:

Tracks 5 and 6: Multiple voices resonating in dome of building, Perugia (length 02:01) and Sea cave, Cornwall (length 01:59). Field recordings by the composer, Wilkins. Reproduced with permission.

An in-between, a time-lag. In musical terms it means to vary the emphasis on a series of sounds and thus avoid a regular rhythm, accenting a weak instead of a strong beat or introducing a sudden change of time.

The various meanings of the word according to Marsilio Ficino, as referenced by Dalmasso (2001), include that of the sleep or the swoon, signifying a state of emptying, a release. In terms of sound this comes close to a suspension of time generated by the repetition of cyclic sounds, or by a series of compressions, collisions, sonic frictions. A non-narrative form of musical discourse that cuts into its own sonic material, producing fragments not normally included – parentheses, a-vocal sounds, hesitant repetitions.

The gap, according to Dalmasso, that renders groundless/speechless on ‘coming-to’ (188) from a state of syncope. Speech as an ‘audible gaping’ (188) invokes Figure 1 of Lucrezia, the Talking Statue:

Track 7: zaum 2 (length 01:53), Wilkins/Ben-Tal, O. 2009. Reproduced with permission from the authors.

An emergence of something that arises unexpectedly, from the recesses of a situation, if it is indeed allocated a place of possible disruption.

Un-thought.

Badiou’s ‘language of flight […] locating a vanishing point’ (Dalmasso 187 citing Badiou [2008] 2009 132):

Track 8: zaum 1 (length 00:35), Wilkins/Ben-Tal, O. 2009. Reproduced with permission from the authors.

Darkness onstage, the end of a film, the un-heard of:

in sonic terms the flip-side of a recorded source such as the mechanism of a piano roll re-winding like that of a reel of film. Or the shellac disc of a gramophone repeating at the end of its ‘locked groove’ (Wilkins 1986).

Extraneous sound exposed as an underside, a reversal:

Track 9: excerpt from Mecanica Natura (length 02:00), radiophonic work, (Wilkins, 1999). Reproduced with permission from the author.

Dalmasso’s ‘collective cantillation’ (188), a play of chanting, reciting voices, delves into an unconscious world that surfaces unknowingly.

It recalls Track 6 of my sonic fragments:

multiple voices of an audience recorded in the resonant space of an anteroom before a performance.

This encounter with two plays framed by their authors’ essays has led me on a journey of creative responses that plunge into a personal aural memory and association of things read or otherwise experienced. For the practitioner-philosopher this journey reflects a movement of thinking through doing, in other words, through performing, whereby the two can never really be separated. There is the philosopher- actor addressing their own multiple identities, leaving each of these strands open to interpretation. A ‘theatre of the world’ is created, one in which objects and everyday occurrences can assume another more timeless role. Parallel realities occur within the plays, both between the performers themselves and with their audiences. There is an ambiguous sense of time and space, of absence and presence, made possible by combining different strategies of theatre taken from film, sound, gesture, word and scenography. The result is an expansion of thought into areas of perception not otherwise encountered. What is unknown is allowed to surface and re-encounter conscious thought on a slightly different plane. The suspension of the possible occurs through surprise, shock, and an emptying of expectations. Freed from representational values, creative thought delves into multiple levels of existence, giving initial credence to its powers of un-thought in the process.

These are some of the arguments that invite performance philosophy into the arena of this book and vice versa. Derrida | Benjamin has profound importance for any practitioner working in this field through its framing of the performative within the act of thinking. Indeed, from the viewpoint of any future realisation of the plays themselves there is tremendous scope for their adaptation to other forms of live/virtual performance, such as radio drama, film, inter-medial performance and even installation-performance.

Badiou, Alain. [1982] 2009. Theory of the Subject. Translated by Bruno Bosteels. London: Continuum.

———. [2008] 2009. Pocket Pantheon. Translated by David Macey. London: Verso.

Benjamin, Walter. 2002. The Arcades Project. Translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

———. [1929] 1996–2003. “Children’s Literature” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, 2.1 vols, eds. Howard Eiland and

Michael W Jennings, and Gary Smith, pp. 250–256. London: Harvard University Press.

———. [1932] 2014. “Much Ado About Kasper”, in Radio Benjamin, edited by Lecia Rosenthal, translated by Jonathan Lutes et al. London: Verso.

Dalmasso, Fred, Véronique Dalmasso, and Stephanie Jamet, eds. 2017. La syncope dans la performance et les arts visuels: Syncope in Performing and Visual Arts. Paris: Le Manuscrit.

Diderot, Denis. [1796, 1830] 1966. Rameau’s Nephew / D’Alembert’s Dream, translated by J. Barzun and R. H. Bowen. London: Penguin.

Ferrante, Elena. 1992. Troubling Love. Translated by Anna Goldstein. Rome: Europa Editions.

Ficino, Marsilio. 2001. Platonic Theology, 6 vols. Translated by Michael J. B. Allen. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Goebbels, Heiner. 1998. Max Black, music theatre. Accessed April 29, 2022. www.heinergoebbels.com; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RPUtkzqOf0M; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C5t7yPlcHfM

Janecek, Gerald. 1996. Zaum: The Transrational Poetry of Russian Futurism, San Diego: San Diego State University Press, Accessed March 21, 2023.

Jones, Leona, and Caroline Wilkins. 2022. “With W/Ringing Ears.” In Performance Philosophy 7(2): 149–156. https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2022.72350

Martone, Mario, and Elena Ferrante. 1995. L’Amore Molesto, film. Lucky Red (2004. Italy, DVD). Accessed April 29, 2022. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0112352/; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1EY_FFfT-KM

Rokem, Freddie. 2015. “The Processes of Eavesdropping: Where Tragedy, Comedy and Philosophy Converge.” Performance Philosophy 1: 109–118. https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2015.1120

Von Trier, Lars, 2022. Accessed April 29, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lars-von-Trier

Wilkins, Caroline. 1986. Piece for accordion and phonograph : for solo accordion & gramophone. https://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/workversion/piece-for-accordion-and-phonograph/6895

———. 1986. Music for mechanical instruments : electro-acoustic work.

https://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/workversion/music-for-mechanical-instruments/6893

———. 1999. Mecanica natura : radiophonic work. https://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/workversion/mecanica-natura/19638

———. 2016. “The Panacousticon: By way of echo to Freddie Rokem.” Performance Philosophy 2(1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2016.2179

———. 2017. “Zaum: Beyond Mind — Beyond Time?” Polysèmes: La Démesure du temps. https://doi.org/10.4000/polysemes.1906

Wilkins, Caroline, and Oded Ben-Tal. 2010. Zaum : beyond mind : sound theatre for voice and live/interactive electronics. https://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/workversion/zaum-beyond-mind/24538

Independent composer/performer/researcher Dr. Caroline Wilkins completed a practice-based PhD in Sound Theatre at Brunel University, London in 2012. She comes from a background of new music performance, composition and theatre, and has worked extensively on solo and collaborative productions involving these. Her particular interest lies in exploring new forms within the field of inter-medial sound theatre.

She has presented extensively at (inter)national conferences and published articles / essays in both book and journal form, including O.U.P., Intellect Books and Journal of Performance Philosophy.

Website: http://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/artist/wilkins-caroline

© 2023 Caroline Wilkins

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.