Christina Kapadocha, East 15 Acting School, University of Essex

The following practice aims to support you in sensing and cultivating embodied thinking through self-directed touch as the ground of your reading experience. I would like to fully acknowledge the limitations of not being “in the room” with you, but also explore the participatory possibilities presented here towards an experiential perception of this article’s critical analysis. I will intentionally not interrupt this facilitation with contextual information at this point, even though underlying philosophical ideas can easily be discerned and will be brought up later in this writing.

The invitation is to approach each offered principle with curiosity and creativity, taking as much time as you need for each step and the transitions in between. If helpful, you could also expand your reading experience by watching Video 1.[1] In the spirit of fostering agency in your reading experience, if you choose to watch the video as part of this introductory practice, I prompt you to respond to your own witnessing—possibly pausing, rewinding, skipping, or simply observing.

Video 1: https://vimeo.com/1141672269

This is a practice on touch or physical contact. Non-sexual—I have to bring this “in the room”—personal, self-directed, caring, hopefully resourceful touch. The secret is that intentionally this study does not involve physical contact with someone else. “How is that possible?” you may ask. Hopefully you will sense….

First, as I open up the theme of touch or physical contact, my invitation to you is to softly, without overthinking, attend to three words that come up in your mind when you read the words “touch” or “physical contact”. Acknowledge them, try not to judge them, write them down or speak them aloud, and simply keep them in your attention.

Now let’s delve deeper into what touch can be, focusing on your individual embodied experience based on five principles: 1. source of contact; 2. points of contact; 3. pressure of contact; 4. movement of contact; and 5. contact with the space.

Find a comfortable sitting position wherever you are. I would like to offer the first principle in this “reading” of touch we are exploring—the “source of contact”. Can we agree that when we think of source of contact the first organs that may come to our minds are our hands? If so, I would like to invite you to mindfully bring your hands together in any way you wish to. As if you are about to greet yourself. You may not have to change anything if your hands are already somehow together. Just to give you options in case this will bring you more comfort, it may be palm to palm. It may be interlacing your fingers. It may be one hand on top of the other with your palms facing up. It may be one palm facing down the other palm facing up. When you arrive there, I have a philosophical question for you but let’s try not to make it too heavy. Can you distinguish which hand is touching and which hand is touched?

Now I would like for you to focus on the actual “points of contact”, let’s delve into the detail. As your hands are meeting, which little bits come together? Is it the tips of your fingers with the bottom of your palm? It can be the tips of your fingers touching the knuckles of the other hand. It can be the full surface of your palms meeting. My invitation is for you to start moving between smaller and larger points of contact. Only that, dwell in the simplicity of that. Allow this journey, this ongoing transition from smaller to larger points of contact. Only with your hands. I would like for you to notice how we start playing with some sort of hand-based, touch-based “choreography”. Only with that; the journey from smaller to larger points of contact.

As you do that, I would like to introduce the next principle—“pressure”. What if you allow your hands to meet as if you touch the surface of water? As if you don't want to change something; as if you don't want to direct; just be there, zero of pressure, no pressure at all. And notice—because I’m with you through my own experience—what may be happening to your breathing? What may be happening to your attention? What may be happening even before you allow this contact which gives space in the experience—or at least this is the intention. Respond to what feels right and supportive for you; start adding pressure only to the extent it feels nice; play with different levels of pressure. It may be just adding a little bit of resistance; it may be offering more pressure. The more you play with that, notice how the different levels of pressure starting from your hands can affect the rest of your body.

Of course, we have been moving through our hands, but movement hasn’t been our primary guide. So now I would like for you to focus on “movement”. What sort of movements can come up between your two hands? It may be rubbing; it may be brushing; it may be patting; it may be tapping; it may be stroking; it may be active stillness. Allow yourself to go for any sort of movement you wish to explore in between your hands; another step in this touch-based, hand-based “choreography”. And, as you’re focusing on movement, you may realise that the source of contact is there; that the points of contact are still there; that the levels of pressure are very much still there.

When you establish this awareness, let’s return to the source of contact. Now, I invite you to take whichever movement feels right for you, and start using it on the rest of your skin body. It may be that you take patting and you literally start mapping the rest of your skin organ. Don’t forget any little bit of this “landscape”. You may wish to shift from one movement to another when you meet different areas of your skin organ. It may be brushing in the length of your limbs; it may be tapping on your face; it may be using the wholeness of your palm and just allowing a little bit of stillness. You may start realising the sounds that can come up. As you do that, you may find yourself wanting to become a little bit more active; you may not. But if you do, please feel free to respond.

If you’re there—I want to give you all the options—you may start noticing that you can move away from only hands-to-body, and you can start meeting more unexpected points of contact. It may be your upper arm meeting the inner part of your thigh. It may be your elbow and your knee. Start mapping all the different possibilities of points of contact through the full source of your skin organ.

Now you may realise that organically you meet the “skin of the space”; and you meet the skins of the space if you come across different qualities. From body-to-body points of contact, move your attention to body-to-space points of contact. Listen and facilitate the size and the extent to which these come up for you. You may notice that now the source is the wholeness of your skin. You might have moved beyond your hands, but you still have the clarity of very specific points of contact. Focus on the points of contact that want to move you, whether body-to-body or body-to-space points of contact. Observe that you still play with pressure. It can be quite interesting to go for the zero of pressure in relation to the skin of the space; and then adding pressure, what comes up? Keep playing with movement; you can slide, you can stomp, you can rest, you can observe. Notice your points of contact and then allow them to move you.

Go for it, bring all the principles together through your curiosity.

As part of this integration, you may find yourself wanting to sound or to speak through your first-person observations. You could try saying “I touch and …” or follow through with any other verbal or non-verbal creative expression that emerges. You might also take this further into writing, noticing any new expressive forms that arise from the attention you have cultivated. Acknowledge how you wish to bring this practice to a close. Do you notice that we have set up the ground of a dramaturgy together?

This experiential opening serves, in practice, as an entry point into what I introduce here as inter-embodied dramaturgies within participatory performance practices. Inter-embodied dramaturgies propose both a practical and theoretical—or, in one word, praxical—framework for cultivating critical awareness and facilitating contingent dynamics between practitioners and participants. As a set of philosophical principles embedded in practice, they seek to foster inter-embodied attention infused with ethical perspectives on diverse interconnection and differentiation. As a praxical methodology grounded in its philosophical implications, it offers a flexible structure that enables participation to unfold across both participatory workshop and performance contexts, supporting adaptable modes of inter-embodiment through self-directed touch and somatically inspired facilitation.

More specifically, the outlined tactile principles were developed through the Practice-as-Research (PaR) project From Haptic Deprivation to Haptic Possibilities, which explores somatically inspired methods for cultivating creativity, care, wellbeing, and the beneficial potentials of touch through participatory research activities.[2] Initially designed in response to COVID-19 physical distancing guidelines in performance training and production, the project centres on a structured investigation of self-directed touch. This is touch initiated and managed by oneself in relation to one’s own physicality and environment. Italicised extracts in this article are drawn from the documented facilitation of the performance-workshop Are We Still in Touch?, which anchors the project’s in-person group activities and serves as a case study of an evolving inter-embodied dramaturgy. These extracts, alongside video documentation, are embedded to offer a direct connection to the performance-workshop as inter-embodied dramaturgy in practice.

In this context, dramaturgy is understood both as the arrangement of structure and content within the project’s practical sessions and performance-workshops, and as a dynamic practice integral to the process of performance-making. Thus, although the performance-workshop discussed here is not a participatory performance per se, it is considered an event that manifests a form of dramaturgy—one that can potentially lead to a performance as part of a sustained creative process. This understanding aligns with postdramatic perspectives that extend dramaturgy beyond traditional performance settings and recognise all compositional elements that contribute to performance-making, including how bodies act and interact.[3] For instance, dramaturg and academic researcher Maaike Bleeker (2023) outlines her expanded concept of “doing dramaturgy” and thinking through practice, pointing out “new perspectives on what dramaturgy can be, and how it can be part of creative processes” (24). Drawing on Fiona Graham (2017) and David Williams (2010), Bleeker notes that “every performance, and many other things as well [such as meetings, conferences, presentations] can be said to have a dramaturgy that is embodied in how they are constructed” (24).

Notably, and in resonance with Bleeker’s ideas on expanded dramaturgies, I observed that the five principles introduced in the opening practice—source of contact, points of contact, pressure of contact, movement of contact, and contact with the space—together with the arising structures, movement, and poetic language can be considered a form of dramaturgy. Furthermore, I began to cultivate a dramaturgical awareness: one attuned to inter-embodied narratives, emergent structures, and non-verbal expressions co-created with participants. This evolving awareness additionally aligns closely with Vida Midgelow’s (2015) concept of “dramaturgical consciousness” in improvisatory dance performance: an embodied, reflexive, and critical awareness that enables practitioners to navigate “uncertain territories” with adaptability and responsiveness—qualities she identifies as fundamental to dramaturgical practice (110–111). A similar requirement for contingent reflexivity also underpins the PaR and somatic methodological strands of this project. They are summarised as openness to the “not-yet-knowing” in PaR (Heron and Kershaw 2018, 37), and a cultivated availability to what lies beyond conscious knowledge in somatically informed embodied inquiry (Leigh and Brown 2021, 15–19). As a practitioner-researcher who initiates and facilitates this investigation, I step into the dynamic role of the performer-facilitator, simultaneously becoming an active dramaturg. Midgelow’s notion of dramaturgical consciousness refers to how the practitioner, the improviser in her context, can assume dramaturgical responsibilities from the inside of the practice’s embodied experience, without separating improvisation from dramaturgy and critical awareness (2015, 177).

Inspired by this evolving dramaturgical consciousness within a research methodology that brings together PaR and somatically inspired inquiry in performance praxis, this article does not aim to offer a comprehensive study of dramaturgy. Instead, it engages with dramaturgical thinking as an emergent conceptual framework developed in dialogue with the project’s philosophical underpinnings grounded in embodied phenomenology and feminist perspectives on inter-embodiment. My approach acknowledges a dynamic conversation with existing dramaturgical discourses, such as Bleeker’s and Midgelow’s concepts introduced above, in which embodied, practice-based, and critical perspectives on dramaturgy intersect with a specific focus on inter-embodied ethics, care, and meaning-making.

The term inter-embodied dramaturgies is introduced here to highlight and expand on how dramaturgy can emerge not from a singular, objectified view of the body as a physical entity for composition, but through inner-outer dynamics, interrelational plurality, and the differentiated lived experience of conscious, sensing, and thinking co-participation.[4] Importantly, this view resists an essentialised notion of the unified or idealised body as a fixed, universal category. Instead, it embraces a de-essentialised understanding of embodiment as multiple, situated, and co-constituted between diverse individuals through relational contexts. Here, embodiment is not confined to an individual’s physical form but is understood as a shifting condition of being-with others—shaped by inner–outer dynamics and by differences (ethnic, racial, cultural, perceptual, ethical, etc.)—and unfolding through conscious, reciprocal engagement.

To elaborate on intercorporeal dynamics and how self-directed touch cultivates inter-embodied potentials—even without direct contact with another person—this research draws on Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s embodied phenomenology, particularly his notion of flesh. Merleau-Ponty’s foundational concepts are extended through feminist critique that foregrounds difference and plurality in contrast to the universalising and unifying tendencies of his fleshiness. Through the lens of touch, inter-embodied resonances are explored in praxis, aligning with principles of relational proximity articulated by Sara Ahmed and Jackie Stacey in Thinking Through the Skin (2004). Ahmed and Stacey frame inter-embodiment as “a way of thinking through the nearness of other others, but a nearness which involves distantiation and difference” (7). Inter-embodiment here refers to a relationality that acknowledges both proximity and separation, enabling the experience of connection with others while maintaining individual perspectives and agency. Ahmed’s broader ethical orientation towards “being with” differently (2000; 2005; 2006) further supports the project’s investigation of self-directed touch not as an autonomous or predetermined act, but rather a latently interrelational one that evolves within a shared field of diverse embodiment.

Praxically, the project’s tactile nature is inevitably situated within a framework of “haptic dramaturgy” (Walsh 2014, 58), contributing to PaR academic studies that investigate interrelational dynamics and participation through somatically informed approaches to touch. In addition to Midgelow’s artistic research within the context of dance dramaturgy, other relevant examples include Lisa May Thomas’ (2022) investigations into touch-based interpersonal dynamics, particularly within technologically mediated processes; Paula Kramer’s (2025) focus on tactility and environments (2025); and Emma Meehan’s (Carter and Meehan 2020) research on aspects of interpersonal touch and chronic pain in performance and health contexts. Haptic Possibilities contributes to these approaches by placing self-directed touch at the centre of the investigation. Especially in the wake of societal shifts catalysed by the pandemic, including issues of isolation and mental health, carefully facilitated personal tactile experience appears to afford not only individual embodied presence and agency but also deeper relationality and collective dramaturgical inquiry.

Moreover, the performance-workshop Are We Still in Touch?, as a case study of an inter-embodied dramaturgy, extends beyond the methodological intersections of dance and somatic practices examined in the above PaR studies. It broadens the awareness of multidisciplinary dramaturgical participation by studying open invitations for participants to become co-creators, co-performers, and co-investigators positioning them as active contributors to an emergent dramaturgy. Drawing, among other influences, on my Greek cultural and theatre background—which, while white, sits outside dominant Euro-American traditions—the philosophical and practical underpinnings of the practice also contribute to critiques of the essentialised body within somatic dance methodologies. These critiques include Doran George’s (2020) challenge to the concept of the “natural body” in somatics, Royona Mitra’s (2021) intersectional analysis of supposedly “democratic” touch in Contact Improvisation (CI), and Sarah Holmes’ (2023) investigation of white fragility and privilege in somatic discourse.

Within this expanded and critically informed framework, the performance-workshop investigates inter-embodied dynamics and emergent dramaturgical processes through the facilitation and performativity of the integrative role of the performer-facilitator. The practice asks: What new dramaturgical and ethical possibilities arise when participatory, somatic, and performance methodologies intersect? How might the roles of facilitator and performer co-constitute one another through embodied presence and responsiveness? And crucially, how can touch that does not involve direct physical contact still generate experiences of inter-embodiment and relationality? In this context, dramaturgy is carefully designed in advance, yet flexible enough to accommodate the particularities and emergent dynamics of each group.

Aiming to echo the nature of this structure in this reading experience, I opened this article by guiding you through the basic Are We Still in Touch? dramaturgical steps: 1. considering three words on touch; 2. experiencing the five principles of self-directed touch; and 3. reflecting creatively. In the following sections, I will maintain the performance-workshop’s structure in dialogue with critical aspects on inter-embodied dynamics between myself and the project participants. The complementary video documentation similarly follows the unfolding of the process and preserves the cohesive development of the practice as it was experienced across different iterations.[5] Beyond demonstrating the practice itself, the embedded videos aim to illustrate the principles of the discussed methodology through examples of dynamic and diverse inter-embodiment, analysed throughout this article. To this end, I integrate in the writing specific video excerpts, as I did for the opening practice above, and “curate” your attention to what I consider potentially valuable contributions to wider participatory practices and research. Nevertheless, I do not mean to be prescriptive; you may prefer to engage with the videos in a different manner.

Based on what Robin Nelson (2022) identifies as “moments of insight” in PaR (55, 90), I aim to acknowledge such moments in the performance-workshop and unpack inter-embodied dynamics in them based on this discussion’s critical framework. By combining conceptual information and critical analysis (in standard format) with video documentation, facilitation extracts (in italics) and participants’ reflections (as quotes), my objective is to invite a holistic engagement with the discussed argument and methodology, both cognitively and experientially. The Are We Still in Touch? material interwoven here draws from the fourth iteration of the performance-workshop, as it took place at the Siobhan Davies Studios in South London on July 2, 2023. This iteration, compared to others, leveraged the artistic identity of the space, the spaciousness of the studio and the performance backgrounds of most participants. These factors expanded possibilities for performativity and facilitated diverse video documentation of the process.[6] Additionally, prior to the session, I planned to test more overtly dramaturgical components of “haptic scenography”, adding floor cushions, fabrics, and other natural materials like ropes for participants’ active engagement (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Participant interacting with hanging ropes as part of the Are We Still in Touch? haptic scenography at Siobhan Davies Studios, London, July 2, 2023. Scenography collaborator Mayou Trikerioti. Photo by Christa Holka.

Bringing together the practical and theoretical components outlined above, this article analyses how the structure and content of the Are We Still in Touch? dramaturgy can create a space for co-expression, co-performance, and inter-embodied thinking between participants and the practitioner-researcher. This contingent dramaturgy seeks to challenge structures of embodied homogeneity, hierarchical themes, and deterministic expectations, positioning performance philosophy, conceptual philosophy, and embodied practice in dynamic interaction. Ultimately, this discussion proposes that inter-embodied dramaturgies, as part of participatory performance and research practices, can both contribute to performance praxis and deepen ethical awareness in collective care, potentially opening new pathways for relational and societal transformation.

Are We Still in Touch? begins as the performer-facilitator, myself, extends a non-verbal welcome to all individuals in the studio, inviting eye contact as a somatic gesture from participants who choose to actively engage. With eye contact approached as a complex and intimate gesture of somatic witnessing, this opening aims to set the tone for the performance-workshop’s focus on relationality while acknowledging the interaction between the practitioner and each person in the group. From a dramaturgical perspective, this enactment exemplifies what Bleeker (2023), building on Donna Haraway’s concept of response-ability, articulates in her discussion of doing dramaturgy as “a praxis of care that involves the capacity to attend to and respond within the messy worlds we inhabit and participate in” (1). In my experience within the moment, presented in the brief Video 2 below, the non-verbal communication of this intended care cannot be assumed, and I am fully aware of my ethical responsibility to cultivate it attentively as each event unfolds.

Video 2: https://vimeo.com/1141672300

The initial non-verbal welcome through eye contact is followed by contextual information, including a brief introduction to my professional identity and the Haptic Possibilities project. In resonance with Bleeker’s association of dramaturgical practice with ethical and caring response-abilities, grounded in specific skills and expertise, I recognise the ethical need to outline my professional journey. In doing so, I frame the facilitation of the performance-workshop within a trajectory of sustained development spanning nearly two decades. Educationally, I highlight key steps: graduating from the Greek National Theatre Drama School (2008), completing fully funded postgraduate studies in the UK—an MA in Acting (2011) and a PaR PhD in Actor Training (2016)—and obtaining a diploma as a Somatic Movement Educator and Therapist (2016). It is important for me to clarify to participants that, while movement therapy informs my work, it is not its primary intention; rather, it operates as an undercurrent supporting the performance-workshop’s somatic dimensions.

Although I do not explicitly state this, my professional trajectory also influences how I attune to inter-embodied dynamics within the group through a somatic mode of witnessing. In the somatic practice of Authentic Movement, studied as part of the Integrative Bodywork and Movement Therapy (IBMT) Diploma training I undertook, somatic witnessing refers to an embodied state of active engagement, requiring the witness to attend to others while remaining attuned to their own physicality, senses and sensations, feelings and imagery (see Adler 1999, 154; Hartley 2004, 63–67). While this witnessing attention has primarily therapeutic applications, modifications of somatic witnessing inform my methods as an active performer-facilitator within the performance-workshop. These modifications, manifested in the form of verbal and/or non-verbal interactions, aspire to cultivate inter-embodied dynamics between myself and the participants, while I maintain a conscious awareness of my own experience. This process also reflects Midgelow’s concept of dramaturgical consciousness within the dancer’s improvisation.

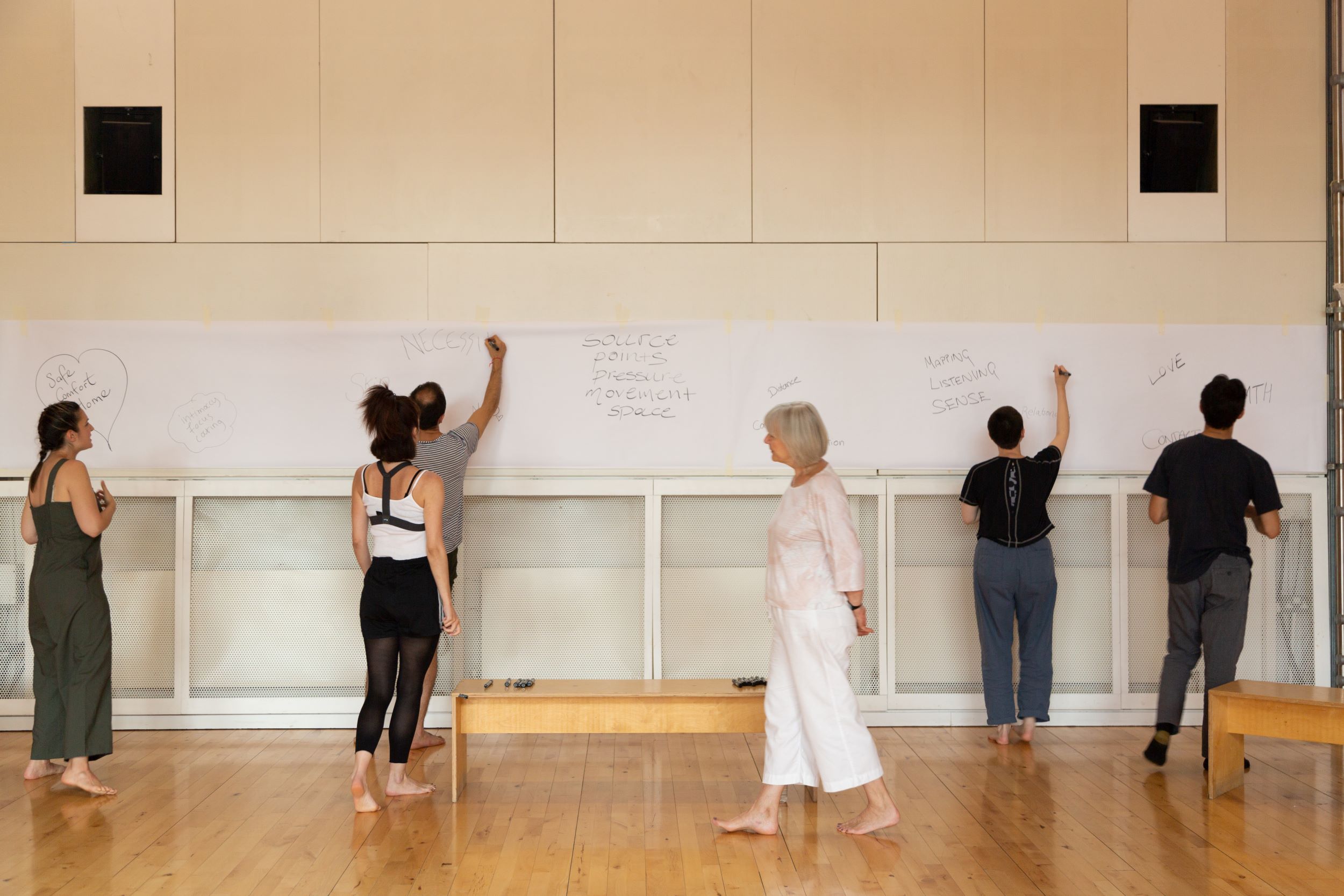

For instance, my first invitation to participants is to think and write down three words on touch based on free cognitive association, as I also prompted you in the opening practice. I explain that they may choose to record their words privately on their questionnaires or more playfully by writing them with markers on large paper rolls placed on one wall and one side of the floor (see Fig. 2). My witnessing in this section involves sensing how the arising words register in my body and voice as I read them out loud. In Video 3 you can observe this physical-vocal interaction and how my voice shifts from higher to lower pitch as I read different words and move between spots in the space, responding dynamically to the participants’ contributions. I understand this mode of witnessing as a dramaturgical component that opens possibilities for performativity and for emergent associations between different words. In my perception, this witnessing intrinsically becomes a method for navigating dramaturgical consciousness as it arises relationally between the performer-facilitator and the participants. My intention is not to impose or monopolise the expression but to recognise and validate all associations through my own embodied process, while fostering active engagement, creative, and critical awareness within the collective.

Video 3: https://vimeo.com/1141672316

Fig. 2. Performer-facilitator and audience-participants interact as the participants write on the large paper roll on the wall and they observe each other’s responses. Are We Still in Touch? at Siobhan Davies Studios, London, July 2, 2023. Photo by Christa Cholka.

To transparently interrupt my prominence in the room, I then invite participants to look around at each other’s words and verbally express their responses either to what they wrote or to someone else’s contributions.[7] This shift aims to decentralise my authority and support the project’s emphasis on reciprocal relationality. As part of my facilitation, I explain that the intention behind these prompts can be summarised in the phrase “to feel the skin of the group” or, more precisely and in line with the project’s focus on plurality and differentiation, to feel the skins within the group. This articulation and practice resonate directly with Sara Ahmed’s conceptualisation of “the skin of the community”, which describes how the negotiation of physical proximity and distance is affectively shaped through processes of alignment and disalignment.

In her essay on affect and boundary formation, Ahmed (2005) writes: “it is through moving toward and away from others or objects that individual bodies become aligned with some others and against other others, a form of alignment that temporarily ‘surfaces’ as the skin of the community” (104). By inviting participants to respond to one another’s words and presences, the facilitation actively engages with Ahmed’s proposition that community is not given but is surfaced. It is emergent, taking shape through movement and affective proximity. The participants’ shared yet differentiated responses give rise to what Ahmed terms a “temporary alignment”, which in the context of the workshop becomes an inter-embodied texture of togetherness. Rather than seeking unity, the practice supports a felt sense of plural belonging that embraces difference.

Participants appear to align as they bring up connections between tactile warmth and calm, touch as a way of feeling visible, mapping the body, communicating between other animals (such as chimpanzees), and surviving. I verbally echo sentences from their responses like “it helps me feel calmer” and “[it] makes me feel present, alive, here, visible, seen”. In this context, alignment manifests as a collective reference, forming a temporary “skin of the group” that holds, rather than overrides, the particularities of each participant’s contribution. This approach to collective subjectivities also echoes the project’s investigation of embodiment as active, interrelational and diverse dynamics that connect us by being bodies with processes such as thinking, imagining, feeling, sensing, and creating, along with evolving interactions with our environments and others. This philosophical framing of somatically inspired embodiment underpins the project’s methodological framework.

From actor-training to performance environments, my research has been occupied by critical interrogations of mind-body, inner-outer, self-other intersubjective dynamics using somatically inspired methods such as gestures, movement, touch, verbal or sound input (see Kapadocha 2016; 2018; 2021; 2023). These dynamics, as modes of being and perceiving, are philosophically aligned with Merleau-Ponty’s discourse on embodied phenomenology, his notions of the lived body and the flesh. Adding to phenomenological ideas introduced by Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty ([1945] 2002) emphasises the experience of the world through a body which is simultaneously object and subject of perception: as “we are in the world through our body” and “we perceive the world with our body” we also rediscover our self as both a natural self (an object) and a subject of perception (239). The most important aspect in the connection with the world for Merleau-Ponty is communication with others, described by the philosopher through the concept of intersubjectivity:

I experience my own body as the power of adopting certain forms of behaviour and a certain world, and I am given to myself merely as a certain hold upon the world; now, it is precisely my body which perceives the body of another, and discovers in that other body a miraculous prolongation of my own intentions, a familiar way of dealing with the world. (Merleau-Ponty [1945] 2002, 412)

This interrelation is expressed more fully in the philosopher’s understanding of the flesh. The relational engagement suggested by the porous quality of the flesh as a “feeling” or concept allows a simultaneous dialogue between internal and external, self and other perception, resembling actual characteristics of human body structures such as the skin organ, the prominent locus of investigation in the Haptic Possibilities project. Merleau-Ponty ([1964] 1968) invites the reader to think of the flesh not as a union of contradictories but as “an ‘element’ of Being” (139, 147). Inspired by Sartre’s Being and Nothingness ([1943] 1989), Merleau-Ponty’s flesh represents the exemplar sensible, the body that is at the same time sensible and sensate—the body that touches and is touched, as enacted in the discussed practice (135). An extension of the relation with the embodied self is the world which, as it is perceived by the flesh body, it also reflects the element of the flesh (248, 255). This experiential thinking sheds light on possibilities that can arise from tactile reflexivity empirically examined in the performance-workshop.

Despite Merleau-Ponty’s pivotal contributions to recognising embodied and interrelational perception, his ideas seem to provide little acknowledgement of embodied differences in multiple and diverse subjectivities. This brings forward the issue of the one-universal body, which I have previously addressed in my research challenging logocentric problematics of dualism and universalism in actor-training discourses (see Kapadocha 2016; 2021). Feminist theorists have crucially filled this “gap” in the philosophical discourse on embodiment. As Ahmed and Stacey (2004) point out, “for feminist, queer and post-colonial critics there remain the troubling questions: If one is always with other bodies in a fleshy sociality, then how are we ‘with’ others differently? How does this inter-embodiment involve the social differentiation between bodily others?” (6). They caution against fetishising the singular body as an abstract or lost object, addressing instead the question of embodiment through “a recognition of the function of social differences in establishing the very boundaries which appear to mark out ‘the body’” (3). What they propose is a critical approach to inter-embodiment that acknowledges the nearness of others while simultaneously recognising boundaries and distinctions that shape individual embodied experiences (7).

This emphasis on difference and boundary formation is further analysed in Ahmed’s writings, including her critique of Merleau-Ponty’s formulation of inter-embodiment in Strange Encounters (2000). She challenges the ease with which Merleau-Ponty moves from individual embodiment to a presumed collective “our”. Ahmed warns that such universalising tendencies risk flattening difference and obscure how embodied encounters are always shaped by histories, orientations, and the particularities of social life. She writes:

Rather than simply pluralising the body (there are many bodies), this approach emphasises the singular form of the plural: that is, sociality becomes the fleshy form (body) of many bodily forms (our). However, I want to consider the sociality of such inter-embodiment as the impossibility of any such ‘our’. What I am interested in, then, is not simply how touch opens bodies to other bodies (touchability as exposure, sociality as body) but how, in that very opening, touch differentiates between bodies, a differentiation, which complicates the corporeal generosity that allows us to move easily from ‘my body’ to ‘our body’. (Ahmed 2000, 47–48)

Ahmed develops this argument in Queer Phenomenology (2006) by foregrounding sexual orientation as an axis of embodied differentiation. Drawing on Merleau-Ponty’s analysis of touch, she underscores how touch “also involves an economy: a differentiation between those you can and cannot be reached. Touch then opens bodies to some bodies and not others (107). Her model of orientation—spanning spatial positioning, sensory awareness, and relational alignment—dialogues with the project’s emphasis on one’s bodily awareness and differentiation. In Are We Still in Touch?, it is critically acknowledged that each participant’s engagement is not defined by an abstract or universalised embodiment but emerges from orientations sedimented through their lived experiences, identities, and environments. Most importantly, the project implicitly invites participants to reflect on their ways of being with others while negotiating physical distancing and attuning to their own skin organ within “the skin of the group”.

This inevitably raises ethical considerations, which, in line with Ahmed, I experientially and dramaturgically examine as “a question of how one encounters others as other (than being)” (Ahmed 2000, 138; original emphasis). As Ahmed explains, such an encounter is not with a generalised other, but with “a particular other, and the particularity of that other is not given in advance” (2000, 144). As she further notes: “Particularity does not belong to an-other, but names the meetings and encounters that produce or flesh out others, and hence differentiates others from other others” (2000, 144; original emphasis). The performance-workshop’s emphasis on openness to emergent relations can thus be read as an enactment of this ethical framework: that to be with others differently is to remain open to the unknown particularity, and to the ways bodies are re-formed in and through each encounter. I elaborate on ethics as part of the project’s approach to inter-embodiment in the section below. Video 4 and the writing in italics introduce the Are We Still in Touch? “rules” for participation.

Video 4: https://vimeo.com/1141672330

This is a non-judgmental space of invitations, not instructions, invitations. This means that I’m going to be inviting you, and you will be responding as you wish to; if you would like, to the extent you would like; mindfully, physically, both mindfully and physically.

Within my personal space, taking care of myself and taking care of the others; I can stay seated; I can stand up; I can stay on spot; I can move in the space. I can move a little; I can move a lot; I can stay still. I can have my eyes open; I can have my eyes closed; I can be somewhere in-between; in other words, you may be familiar with “I can have my gaze softened”. You can look at me; you can move with me; you can copy me, if that makes you feel more comfortable; you can listen to me; you can just ignore me. Literally, whatever makes you feel at ease with yourself.

To reiterate, for as long as I take care of myself and I respect that every single person in this room is in their own process, it is my responsibility to respond to the invitations as I wish to. [I repeat this three times. The last time I point to the participants, so they echo the word “responsibility”]. I have been given permission. [I repeat again towards the echoing of the word “permission”].

As part of the study on how we encounter self and others differently, the performance-workshop introduces a set of ethical “rules” for self and mutual care. These “rules” are playfully presented as part of an interactive “game” and underpin the whole event. They are supported by elements such as first-person language and verbal-physical echoing. The use of first-person language within this dramaturgy addresses both my own somatic witnessing as a performer-facilitator and the idiosyncratic “I” of each participant. This intentional blurring of roles seeks to encourage co-agency and invites participants to experience the space through their own embodied perspectives. The act of verbal echoing, particularly with words like “responsibility” and “permission”, becomes a method of enacting these principles. It prompts experiential engagement within a shared ethical field. Crucially, these invitations are distinguished from result-oriented instructions. The goal is not to guide participants toward specific outcomes but to support their capacity to make informed choices about their participation.

Watching Video 4, you can observe how I introduce the “rules” in a playful tone, intended to support active and diverse participation. I shift into a more performative mode, expressed through both physical changes and vocal inflection. Using my body, I offer a generic physical articulation of what I am saying, redirecting my embodied focus, both mental and physical, from myself to the inclusion of the participants. This intention is heightened through the repeated phrases on “responsibility” and “permission”, which are delivered slowly and rhythmically. The aim is to create space for participants to engage vocally, physically, and mindfully with these key embodied concepts through the filter of care and within the frame of the group’s collective subjectivities.

I distinguish this introduction to embodiment in the performance-workshop through conscious engagement and a dynamic awareness of self, space, and others. Building experientially on Merleau-Ponty’s discourse, alongside Ahmed’s emphasis on particularity, differentiation, and plural inter-embodiment, I encourage participants to think through their different bodies as lived and shifting entities of relationality. Within the “rules”, this approach is articulated as an interplay between mindful and physical engagement, as opposed to physical engagement alone, though the latter remains a valid and respected choice. However, such engagement may lead to a more mechanical or objectified relationship to movement. In contrast, I situate embodiment as a heightened state of attention that can arise when thinking, sensing, imagining, creating, and being-with converge. In this way, embodiment is not treated as a constant, habitual condition of having a body but as a chosen mode of presence, one we step into consciously, when ready and through various methods.

Ethically, I suggest that this framing cannot emerge from deterministic or result-oriented instructions. Instead, in my experience, participants’ diverse and differentiated inter-embodiment can be supported through methods of somatically informed invitations. As part of a modified approach to somatic witnessing in the performance-workshop, these invitations require an attentive and adaptive mode of facilitation. They are designed to create possibilities for interaction without prescribing predetermined outcomes or expectations. At the same time, extending both Bleeker’s and Midgelow’s concepts, they invite a similarly “response-able” attitude from participants, fostering ethical awareness and mutual responsibility throughout the process. This mutual responsibility also aligns with the requirement for shared care, further connecting the practice to the discourse of “dramaturgies of care” (see Groves 2017; Stuart Fisher and Thompson 2020; Thompson 2023).

Unlike perspectives that position care solely in relation to the interests of those who are cared for (Groves 2017, 117), Are We Still in Touch? situates caring practice within the encounters between performer-facilitator and participants. A dramaturgy of care, according to James Thompson (2023), “is that careful and caring processes of coming together [which] are themselves aesthetically richer than those that might miss or fail to attend to the dynamics of the interactions between people and the quality of the relations that develop between them” (117; original emphasis). Within the context of the performance-workshop, aesthetics becomes a form of inter-embodied communication that is facilitated and somatically witnessed, yet not prescribed. While aesthetic generation is not the explicit aim, the quality of relational encounters inevitably gives rise to aesthetic experience. The intention is not to create synchronicity and homogeneity through physical imitation, but to offer a flexible structure that supports diverse interpretations. It is marked by tactile attentiveness that, when embodied, gives rise to effortless or unforced physical presence and interaction.

This aesthetics of caring togetherness also prompts dramaturgical development. For instance, the distinction between invitations and instructions—along with the “rules” section itself—emerged directly from participant feedback at the end of the first performance-workshop in November 2022. One participant expressed a need for rules on how participation could take form. In response, I introduced the frame of the interactive “game”, listing a range of possible participatory modes as part of “being with” others in the practice. This strategy, grounded in my dramaturgical consciousness, acknowledged the feedback while preserving the project’s non-deterministic intentions around somatically inspired invitations.

As a practitioner-researcher and performer-facilitator in this case study, I am conscious of several challenges posed by the framework of embodiment in the performance-workshop, the practice itself, and the discussed nature of the invitations offered. In alignment with the project’s openness to the “not-yet-knowing” and its ethical commitment to emergent particularities, I remain critically aware that with each iteration, I meet different participants, offer a practice that may not land, and depart from expected formats or traditional workshop facilitation. This awareness enters into dialogue with Ahmed’s framing of encounters, especially her emphasis on differentiation as fundamental to recognising particularity. Building on Levinasian ethics and Derrida’s ethics of hospitality, she writes: “introducing particularity at the level of encounters (the sociality of the ‘with’) helps us to move [ … ] towards a recognition of the differentiation between others, [ … ] and the permeability of bodily space” (2000, 144).

In other words, reading my experience as performer-facilitator through Ahmed’s notion of ethical differentiation, to approach the other is to remain open to an encounter that is not yet decided; one that is not simply a repetition of the same. This openness is not a form of generosity or hospitality that presumes the other must come into being. Rather, it reflects a recognition of one’s own limitations: that the self is shaped through encounters with others. I am aware of the prominence of my role in the “bodily space” of these encounters, and that my invitations may still be perceived as instructions or as a form of controlling facilitation. Yet I can only be responsible for my own intentions and openness as I “hold the space”, aiming to support the emergence of each participant’s differentiation. This includes my modes of inter-embodied facilitation and witnessing, which I analyse in relation to specific video moments in the following section, as well as my conscious shift into the role of witness towards the end of the performance-workshop.

At this stage of the performance-workshop, participants are guided through the five principles of self-directed touch introduced to you in Video 1 and the opening practice: source of contact, points of contact, pressure, movement, and contact with the space. The prompt: Can I distinguish which hand is touching and which hand is touched?, grounds the exploration and aligns directly with Merleau-Ponty’s concept of the human body as both sensible and sensate. Rooted in the lived experience of touch, Merleau-Ponty ([1945] 2002) notes: “when I touch my right hand with my left, my right hand, as an object, has the strange property of being able to feel too” (106). In resonance, the five principles invite experiential engagement with the dual role of our bodies as both perceiving and perceived, aiming to foster the experience of tactile reversibility.

The ethical ground of these inter-embodied encounters can be summarised in what Merleau-Ponty describes as “the zero of pressure”: “it is the zero of pressure between two solids that makes them adhere to one another” ([1964] 1968, 148). In the performance-workshop this “zero of pressure” is introduced in the prompt that invites no pressure between hands: as if I touch the surface of water. As if I don’t want to change something, as if I don’t want to direct it [the point of contact], just be there. It is inspired by the practice of cellular touch in IBMT, a hands-on method which aims at evoking a breathing space between relational points of contact by applying no pressure and visualising human bodies as entities composed of breathing cells.[8] Cellular touch supports the project’s intention to challenge pre-determined assumptions in participatory practices. Its aim is to establish contact, especially self-directed touch, as a non-directive, spacious state, a condition through which diverse experiential possibilities may arise.

In dialogue with the discussed feminist nuances on inter-embodiment, the facilitation seeks to awaken diverse modes of philosophical “thinking through touch”. While watching or re-watching Video 1, I would like to draw your attention to how this relates to embodied qualities in my facilitation—specifically, how my own engagement with the invitations influences the pace of my verbal input and enables a fluid continuation from one principle to the next. This consistent physical, mental, and verbal interrelation sets the tone for the unfolding of my encounter with the participants towards a shared experiential journey. Ahmed’s ethical framework of differentiation and particularity also resonates with the language of the offered somatic invitations, as they prompt each participant to engage with the practice in their own way. This dynamic is reinforced using the plural “bodies”—rather than the body—and through the deliberate use of shifting pronouns “I”, “we”, and “you”, which reflect the layered relationality of embodiment within the work.

Delving deeper into Ahmed’s definition of temporal alignment and permeability in practice, the video offers insight into how inter-embodied dramaturgies and the methods of the performer-facilitator can foster moments of alignment that honour individual particularities. It captures how active participants, even as they respond to the same tactile invitations, cultivate a shared focus or “embodied mind” that emerges from mutual engagement in the task. This inter-embodied alignment arises not from uniformity but from the distinct ways each participant interprets and enacts the shared prompts, contributing to a dynamic sense of togetherness. For example, during the section focusing on points of contact between hands, all participants follow the same prompt. However, their individual responses vary: some sit upright, others recline or lie on their backs, and their positions reflect their personal preferences or accessibilities. While some participants visually engage with their hands, others close their eyes, focusing solely on tactile sensation. These diverse responses illustrate how individual differentiation contributes to a shared interrelational experience, with the performer-facilitator’s prompts creating a structure within which relational dynamics can unfold.

Fig. 3. Audience-participants’ diverse engagement with points of contact between one’s own hands. Are We Still in Touch? at Siobhan Davies Studios, London, July 2, 2023. Screenshot from the event’s video documentation. Videography by Dominique Rivoal.

If you pause Video 1 at two minutes (see also Fig. 3), you will observe a diverse range of responses by participants. Notice the subtle differences between the two participants at the front left who engage with their palms, one seated in a kneeling position, the other lying on their back in grey-blue trousers. The participant in the kneeling posture holds their palms gently in front of their body, hands slightly cupped, with a steady, grounded focus. Their position and stillness suggest a contemplative or centring mode of attention. The participant lying down demonstrates a softer, more relaxed tactile engagement. Their arms float more gently, suggesting receptivity, as their body rests into the floor and cushion, amplifying a sense of ease. These qualitative differences exemplify how shared facilitation can generate differentiated expressions, contributing to a collective experience that values alignment through difference.

In Ahmed’s terms, this dynamic might be understood as the temporary surfacing of a “skin of the community”, where bodies move towards and away from one another not through direct physical contact, but through shared affective and somatic attentiveness. At the same time, the somatic differentiation and distantiation, described in Ahmed and Stacey’s definition of inter-embodiment, do not seem to encourage individuation as atomised or isolated subjectivities. Rather, the practice of self-directed touch in the performance-workshop appears to nurture moments where individual focus supports relational dynamics. Participants’ individual explorations suggest a shared atmosphere of togetherness and manifestations of collective subjectivities. Such moments are visible in Video 5a, where unplanned inter-embodied echoing reflects not a loss of self, but a heightened sensitivity to others through the somatic cues of the shared space.

Video 5a: https://vimeo.com/1141672350

For instance, in response to the invitation for possible movement between participants’ own hands, as shown in Video 5a, a collective physical echoing gradually arises between some of them. Observe in the video how three participants at the back and one towards the front lie on their backs, moving their hands as they extend them in front of their torsos. Notably, considering the principle of physical distantiation in feminist inter-embodiment, this shared echoing manifests not only among bodies in close proximity but also includes others positioned further away (at least the one participant visible within the frame). Notice as well how this echoing evolves into an “unchoreographed dramaturgy” between the four participants in proximity. This is not a direct physical interaction, but an indirect relational quality that emerges through each individual’s attunement to their tactile experience as mediated by the facilitation. While participants remain individually focused, their tactile engagement within a collective space seems to foster a dynamic sense of connection. Their distinct movements and explorations, shaped by common prompts, give rise to a nuanced alignment through difference further analysed in combination with the next video extract (Video 5b).

Video 5b: https://vimeo.com/1141672365

As attention shifts from hand-originated touch to more extensive body-to-body points of contact and then to body-to-space points of contact, Video 5b shows participants expanding their physical movements within the shared space. While remaining anchored in their individual processes, they begin to spatially respond to the shared context, softly breaking from the initial group circle and introducing diverse spatial positions and body shapes. This somatic shift illustrates that differentiation does not fragment the group but contributes to its inter-embodied cohesion, as each participant’s curiosity and unique trajectory enrich the collective environment. The group’s inter-embodied quality arises not from identical responses or direct attention to one another but from an implicit relational framework: each participant’s particular tactile focus shapes and contributes to the collective experience. This reflects Ahmed’s framing of skin not as a boundary of separation, but as a porous site of diverse relationality:

[W]hile the skin appears to be the matter which separates the body, it rather allows us to think of how the materialisation of bodies involves, not containment, but an affective opening out of bodies to other bodies, in the sense that the skin registers how bodies are touched by others. (Ahmed 2000, 45)

Video 5c: https://vimeo.com/1141672380

Witnessing the practice in Video 5c, when the performer-facilitator prompts movement arising from both body-to-body and body-to-space points of contact, and eventually invites the integration of all five principles, you can observe that inter-embodied qualities further diversify. The participants’ varied tempos and approaches coalesce into a group rhythm that is not uniform but inclusive of diverse expressions. This shared yet differentiated engagement cultivates an inter-embodied and caring mind, where the collective is informed by and reflects the particularities of its individual members. I propose that these tactile explorations lay the groundwork for the transition to the next part of the performance-workshop, preparing participants to engage as co-creators and co-performers in the evolving dramaturgical framework. At the same time, as captured at the end of the video, the performer-facilitator gains a moment to step outside the group, shifting into a witnessing role and attuning to how she receives the unfolding encounter before guiding the transition.

This cultivated inter-embodied consciousness now carries into the next phase, where participants move from individual exploration into overt performative participation.[9] Here, the prompts on self-directed touch become a foundation for collective co-creation within a shared dramaturgical framework. The following section focuses on this transformation through inter-embodied dynamics between participants and performer-facilitator, opening with an excerpt from this part’s scripted narrative, which can be witnessed in full in the accompanying Video 6.

Video 6: https://vimeo.com/1141672390

Where is my skin? Where is my skin?/ is that skin? is that skin?/ can I sense it?/here it is/ in the rising and falling movement of my lungs/ the response of my skin as I breathe in and out/ it rises with the inbreath/it falls with the outbreath/the invitation is for you to follow that/even if it is a tiny movement/from your breathing/from this rhythm/ from the rising and falling of your skin/I’m with you.

I’m enveloped/I’m hugged by my skin/from my torso/to my arms, hands/fingers, fingertips/from my upper to my lower body/legs, feet, toes/how do you wish to respond to that?/moving your attention to the wholeness of your skin/the skin/the biggest organ/a moving, flexible membrane/the curiosity of my skin membrane/what does it want to tell me?/looking inwards and looking outwards/at small details and bigger surfaces.

Where does this journey want to take you?/ Touch?/body to body/skin to skin/my skin and the “skins” of my clothes/my skin and the “skins” of the space/the space that holds me/the skin that holds me/ I touch and I’m touched/I hold and I'm held/play with that/ temperature, pressure/different textures, different skins.

How about a touch that doesn’t want to change/to direct/to push/to press/how about a touch that listens, sees/an interplay of the senses.

This extract opens the third section of Are We Still in Touch?, inviting active participants to a form of open co-performance. In my experience and reflection, it is the part that allows the fullest cultivation of dramaturgical consciousness and creative ideas for a latent participatory performance as the participants are invited to freely integrate all the previously investigated principles. They have been informed of this step’s performative nature in the event’s introduction and have been encouraged to remain grounded in their own investigations as they receive the prompts in the text. The scripted text’s poetic style, with its slashes and fragmented lines, reflects a rhythmic, free-verse structure intended to deepen the sense of inter-embodied dramaturgy and to further blend the roles of the performer-facilitator and participants. It also indicates how it was creatively developed drawing on the practitioner-researcher’s reflective witnessing of videos on the project’s online sessions held during the pandemic.

The performer-facilitator’s role evolves into a state of heightened somatic witnessing, balancing a connection to her own experience with awareness and acknowledgement of the participants’ touch-based differentiated expressions in the collective. This dynamic state is visually evident in the video through the performer-facilitator’s somatic witnessing as physical and tactile echoing. Adding to the methods of touch-based somatic invitations, echoing in this part of the performance-workshop is the attunement of the performer-facilitator with the physicalities, chosen points of contact and movements of different participants while they co-perform in dynamic relation to the offered text. As demonstrated in the video, these interactions do not appear as direct imitation but as an attuned relationality that engages in a shared and inter-embodied “third” space. The echoing emphasises the different individuality of each participant’s response through the presence of the performer-facilitator and supports the creation of an inter-embodied space where a collective dramaturgy unfolds.

Distinctive moments of this echoing include the performer-facilitator’s shift from subtle to more active physical expressions, such as when she relates with a participant sliding on the floor, followed by a jumping impulse from another (01:53–02:10 in Video 6). There are also moments of resonance with a participant’s physical state that unexpectedly attunes to the text, as when she lies next to someone and gently places her hand on the side of her lower back while they both begin to roll slowly (05:02–05:24 in Video 6). At 07:45–07:52, an “unchoreographed” synchronicity occurs: the participant in white brings their hands to their face, then elevates and lands on their heels at the exact same moment as the performer-facilitator. After completing the “monologue” section, she continues her somatic witnessing (09:32–end of Video 6), subtly echoing participants’ actions before stepping back once again to the periphery of the group. She then provides time for written reflection, including the prompt for creative writing with the suggested opening “I touch and…”.

The reflective section begins with participants being invited to share their creative writing, if they wish to, through their preferred expressive modes. In the final video extract (Video 7), performative reflections are chosen to suggest a continuation of the discussed inter-embodied dramaturgy. The performer-facilitator maintains a subtle verbal and physical echoing throughout to indicate her ongoing witnessing while recognising in practice the transformative shift in the roles between herself and the participants as performers. The section and Video 7 open with the following sharing:

Video 7: https://vimeo.com/1141672442

I touch and I am restored. I map my body, and I paint myself into presence. I come into contact with the space through my skin and I blend with my environment; it’s relational and there is only beautiful reciprocity. I paint on the canvas of the space with my living, breathing skin, and I come alive on a deeper level, somatically expanding out into an awakening, a waking up from mind trance. I let my body lead and do what it loves. It loves moving and dancing and coming into contact with, coming into connection with, coming into relationship with, so pure and innocent, this holy, sacred, sweet, loving connection; this sweet, loving conversation. I come alive again. Sunlight pours into my skin, hallelujah.

In the video, observe how the participant’s spoken word is integrated with an expansive physicality towards the group and vocal excitement. In resonance but also differentiation, the following two participants choose negotiation with the space and the others, either moving towards the centre of the group (01:29–02:06 in Video 7) or its periphery (02:07–03:22 in Video 7), combining verbal and non-verbal expressions. The final reflection in the video (03:23–end of Video 7) features a participant wearing a GoPro camera, engaging in overt interactions with the group. They choose to move towards various individuals, coupled with attentive physical and vocal expressions. You can notice a quality of care and sensitivity in their awareness along with other participants’ responsive openness.

Additional examples of creative writing from the same performance-workshop include:

I touch and I feel.

I feel love, I am love, I am excitement, excitement about life and more love.

I feel safe.

I found a relation to others, a relation to others …

Intimacy happened.

I feel safe.

I touch and I connect. I touch and I remind myself that I am human.

I touch and I feel internally.

I touch and I understand. I touch and I belong.

The creative reflections are followed by open discussion, during which the theme of relationality remains prominent. In resonance with Ahmed’s ethics of encounters, and broader principles of participatory research, this is something I can help cultivate but not direct, force, or manipulate. Over the course of seven different versions of the performance-workshop (November 2022-June 2024) held in various community, arts, and health-focused settings in London (Good Shepherd Studios, Women’s Health Café, Siobhan Davies Studios, The LightHouse, and Gardens), insights have been gathered by seventy-two participants from different age groups and sectors, among whom health and specialist care workers, wellbeing advisors, artists, arts/movement trainers, educators, and therapists. The participants, among others, have shared a re-appreciation for the role of touch in fostering empathy and intimacy with others and have expressed connections with their groups despite focusing on themselves. In a recent iteration of Are We Still in Touch? for the 16th International Conference of Artistic Research on the theme of resonance (9 May 2025), a participant used the phrasing “collaboration with complete autonomy”.

Returning to the project’s research questions, it is evident that, within its framework, touch-initiated embodied awareness, even at a distance, can facilitate inter-embodied encounters and a sense of collective subjectivities. The praxical methodology of inter-embodied dramaturgies, as proposed in this article, extends the practice of dramaturgy into a realm where self-directed touch, indirect relationality, and somatic engagement are central. Participants’ reflections show how this methodology expands beyond pure physical presence as participation; it engages with deeper layers of embodied knowing, awakening participants to the potential for transformation through somatic engagement and participation. This aligns with the philosophical contributions of the project, its grounding in Merleau-Ponty’s reflexive notion of the flesh and Ahmed’s focus on ethical encounters that negotiate differences, distance, and particularities.

The developed methodology contributes to understanding the experiences and dynamics of both participatory performance and research. It foregrounds the appreciation of ethical complexities inherent in participatory practices, as explored in Are We Still in Touch?, particularly through overlaps between the identities of performer and facilitator, the fused form of a performance-workshop, and the role of somatic witnessing in supporting care within dynamic embodied encounters. Inter-embodied dramaturgies build on embodied aspects of postdramatic approaches, such as those proposed by Bleeker and Midgelow, by emphasising relational and collective dynamics between multiple bodies. They highlight how meaning emerges through interrelational methods, underpinned by ethical principles, differentiation, and the negotiation of proximity. These dramaturgies explore the shared yet differentiated subjectivities that arise in participatory contexts, fostering collective meaning-making grounded in somatic awareness, relational care, and emergent, processual interactions.

Based on the above, I propose that inter-embodied dramaturgies can offer pathways for social change through new modes of practice within and beyond performance settings. For instance, the methodology has potential to enhance inclusivity in performance and virtual, hybrid, or digital settings, where touch and proximity are mediated. It can also be adapted to accommodate diverse sensory needs, including those of individuals with visual or auditory impairments, supporting accessibility in participation. These possibilities were extended in the latest Are We Still in Touch? iteration for the artistic research conference, where a haptic setup generated voice recordings in response to tactile interactions between performer-facilitator and participants. This additional layer deepened the relational exchange and opened further space for inter-embodied dramaturgical consciousness.

The practice can also contribute across examples such as community engagement, educational contexts, health, and wellbeing spaces, where somatic inquiry can support collective and individual transformation. For instance, a later performance-workshop was held in collaboration with Sadler’s Wells Community Engagement Team, as part of their Culture Club activities (19 September 2025). This programme was distinctive in its emphasis on inclusivity across body types, abilities, and ages above eighteen—with particular attention to people over 55—and its focus on encouraging participation, fostering togetherness, and promoting wellbeing through creativity. This collaboration exemplifies how community centres might incorporate the methodology into their programming to support creative and educational engagement.

Community-oriented exercises based on the discussed self-directed touch principles can be used to foster empathy and mutual understanding towards inclusive environments where diverse individuals engage in critical and creative self-reflection. Other applications could include therapeutic contexts, supporting practices of embodied listening, and relational attunement, empowering clients through a structured yet open-ended format that respects individual pace and agency. In educational settings, the work could be adapted to cultivate collaborative learning environments, where students develop interpersonal awareness and empathy by engaging in creative practices that highlight embodied presence and mutual support.

In summary, the methodology of inter-embodied dramaturgies, both as form and a set of principles, invites a reimagining of how we understand what “being with” others implies through participatory performance practices. It suggests that dramaturgy in participatory performance must always allow space for negotiating the particularities of different encounters, challenging predetermined structures, and being inclusive of diverse perspectives and experiences. By foregrounding somatic inquiry, relational ethics, and embodied differentiation, this methodology aims to contribute to the field of performance philosophy, offering a flexible, responsive, and inclusive framework for doing and thinking through performances.

[1] Please note that minor edits have been made to the written version of the original facilitation in this opening section to support the reading experience.

[2] For a concise overview of the wider PaR project From Haptic Deprivation to Haptic Possibilities, including its research activities and outputs, see https://christina-kapadocha.com/practice-research/from-haptic-deprivation-to-haptic-possibilities.

[3] For a concise overview of contemporary and expanded dramaturgy, see, among others, New Dramaturgy: International Perspectives on Theory and Practice (2014), edited by Katalin Trencsényi and Bernadette Cochrane.

[4] On perspectives of embodied dramaturgy that foreground the body as a compositional element, see, among others, Stalpaert (2009), Hansen (2015), Maudlin et al. (2023).

[5] You can also watch the full length of the performance-workshop at Siobhan Davies Studios in July 2023 here https://youtu.be/B4UMtivdQtY.

[6] For instance, to support the first-person perspective in the practice’s video documentation, a participant wore a GoPro during the session.

[7] Please note that the section outlined in this and the following paragraph is not included as a video excerpt here due to its primarily verbal focus. However, it is available in the full event recording (see the video link in note 4, 09:56–14:42).

[8] Cellular touch or contact at a cellular level in Linda Hartley’s IBMT, develops upon the practice of cellular breathing in Body-Mind Centering® (BMC®), founded by Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen (2012, 158–162).

[9] I borrow the use of the term “overt” regarding audience participation in interactive theatre from Murray and Keefe (2016, 123–127).

Ahmed, Sara, and Jackie Stacey. 2004. “Introduction: Dermographies.” In Thinking Through the Skin, edited by Sara Ahmed and Jackie Stacey, 1–17. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203165706.

Ahmed, Sara. 2005. “The Skin of the Community: Affect and Boundary Formation.” In Revolt, Affect, Collectivity: The Unstable Boundaries of Kristeva’s Polis, edited by Tina Chanter and Ewa Plonowska Ziarek, 95–111. State University of New York Press.

Ahmed, Sara. 2006. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822388074.

Bainbridge-Cohen, Bonnie. 2012. Sensing, Feeling, and Action: The Experiential Anatomy of Body-Mind Centering®. 3rd ed. Contact Editions.

Bleeker, Maaike. 2023. Doing Dramaturgy: Thinking through Practice. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08303-7.

Carter, Bernie, and Emma Meehan. 2020. “Bridges between dance and health: how do we work with pain?” Theatre, Dance and Performance Training Blog, January 8. Accessed May 27, 2025. https://theatredanceperformancetraining.org/author/meehanemma/.

Groves, Rebecca M. 2017. “On Performance and the Dramaturgy of Caring.” In Inter Views in Performance Philosophy: Crossings and Conversations, edited by Anna Street, Julien Alliot, and Magnolia Pauker, 309–318. Palgrave Macmillan.

George, Doran. 2020. The Natural Body in Somatics Dance Training. Edited by Susan Leigh Foster. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197538739.001.0001.

Hansen, Pil. 2015. “Introduction.” In Dance Dramaturgy: Modes of Agency, Awareness and Engagement, edited by Pil Hansen and Darcey Callison, 1–27. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hartley, Linda. 2004. Somatic Psychology: Body, Mind and Meaning. Whurr.

Heron, Jonathan, and Baz Kershaw. 2018. “On PaR: A Dialogue about Performance-as-Research.” In Performance as Research: Knowledge, Methods, Impact, edited by Annette Arlander, Bruce Barton, Melanie Dreyer-Lude, and Ben Spatz, 35–46. Routledge.

Holmes, Sarah. 2023. “Racialized Bodily Grammar: A Case Study of White Fragility in the Embodied Discourse of Somatic Practice.” Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices 15 (2): 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1386/jdsp_00114_1.

Kapadocha, Christina. 2016. “Being an Actor / Becoming a Trainer: The Embodied Logos of Intersubjective Experience in a Somatic Acting Process.” PhD diss., Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London.

Kapadocha, Christina. 2018. “Towards Witnessed Thirdness in Actor Training and Performance.” Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 9 (2): 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443927.2018.1462248.

Kapadocha, Christina. 2021. “Somatic Logos in Physiovocal Actor Training and beyond.” In Somatic Voices in Performance Research and Beyond, edited by Christina Kapadocha, 155–168. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429433030-16.

Kapadocha, Christina. 2023. “Tactile Renegotiations in Actor Training: What the Pandemic Taught Us about Touch.” Theatre, Dance and Performance Training 14 (2): 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443927.2023.2187872.

Kramer, Paula. 2025. “Dancing with/in Atmospheres.” In Contingent Agencies: Inquiring into the Emergence of Atmospheres, edited by Alex Arteaga, and Nikolaus Gansterer, 154–164. Hatze Cantz.

Leigh, Jennifer, and Nicole Brown. 2021. Embodied Inquiry: Research Methods. Bloomsbury. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350118805.

Maudlin, Katy, Rea Dennis, and Kate Hunter. 2023. “A Mothering Dramaturgy: The Creative Co-practices of Mothering and Directing in Contemporary Rehearsal Rooms.” Text and Performance Quarterly 43 (2):111–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10462937.2022.2137229.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. (1964) 1968. The Visible and the Invisible. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Edited by Claude Lefort. Northwestern University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. (1945) 2002. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Colin Smith. 2nd ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203994610.

Midgelow, Vida L. 2015. “Improvisation Practices and Dramaturgical Consciousness: A Workshop.” In Dance Dramaturgy: Modes of Agency, Awareness and Engagement, edited by Pil Hansen and Darcey Callison, 106–123. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137373229_6.

Mitra, Royona. 2021. “Unmaking Contact: Choreographic Touch at the Intersections of Race, Caste, and Gender.” Dance Research Journal 53 (3): 6–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0149767721000358.

Murray, Simon, and John Keefe. 2016. Physical Theatres: A Critical Reader. 2nd ed. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315674513.

Nelson, Robin. 2022. Practice as Research in the Arts (and Beyond): Principles, Processes, Contexts, Achievements. 2nd ed. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90542-2.

Stalpaert, Christel. 2009. “A Dramaturgy of the Body.” Performance Research 14 (3): 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528160903519583.

Stuart Fisher, Amanda, and James Thompson, eds. 2020. Performing Care: New Perspectives on Socially Engaged Performance. Manchester University Press.

Thomas, Lisa May. 2022. “Employing a Dance-Somatic Methodological Approach to VR to Investigate the Sensorial Body across Physical-Virtual Terrains.” Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 6 (4). https://doi.org/10.3390/mti6040025.

Thompson, James. 2023. Care Aesthetics: For Artful Care and Careful Art. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003260066.

Trencsényi, Katalin, and Bernadette Cochrane. 2014. New Dramaturgy: International Perspectives on Theory and Practice. Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781408177075.

Walsh, Fintan. 2014. “Touching, Flirting, Whispering: Performing Intimacy in Public.” TDR/The Drama Review 58 (4): 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1162/DRAM_a_00398.

Christina Kapadocha (PhD) is a London-based theatre and somatic practitioner-researcher, founder of Somatic Acting Process®, and Lecturer in Somatic Acting and Research at East 15 Acting School. Her practice research and multimodal publications contribute to performance, voice and community praxis through somatically inspired methodologies. https://christina-kapadocha.com/

© 2025 Christina Kapadocha

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.